This story is a collaboration with the Economic Hardship Reporting Project and Magnum Foundation. We asked photographers to show us the paradox of today’s labor movement. Even as the popularity of unions has grown over the last decade, actual membership has continued to decline. Can new enthusiasm revitalize American labor? Read about this unique moment for workers here.

Domestic workers perform grueling work with few protections. They provide care in isolated settings, leaving their essential labor all too often hidden. It can be a difficult job and a complicated one. When you work in a home, lines blur.

For decades, feminist activists have said that work in the home—often performed for no pay by wives, mothers, and daughters—has been misunderstood as separate from “real” labor. This feminized care has been relegated and detached from a labor movement focused on men.

In the United States, such work has also been done by Black women who have had to organize aggressively against the odds. Infamously, domestic workers were excluded from the labor agenda during the New Deal. And, since then, they have had to fight to catch up to standards enshrined for others in the law. The National Domestic Workers Alliance and others have sought to change the state of play. After the pandemic, there has also been an uptick in interest in movements like Wages for Housework—a campaign in the 1970s to organize and recognize work in the home.

In this project, Chloe Aftel highlights the day-to-day demands of these workers who often go unnoticed. She follows Vivian Siordia and Liezl Japona, both care workers in California, showing the daily ups and downs of such labor. Both Siordia and Japona think that more organizing and aid to care workers could help make the job better.

Care worker Vivian Siordia dressing Colin Campbell, who has cerebral palsy, in the morning.

Colin’s shoes in his bedroom. Siordia has been caring for him for a year. Before, she worked as a teacher.

Siordia lifting Colin out of bed in the morning. “Unionization is important to me,” she says of efforts to organize home workers. “I would like to go in that direction.”

Siordia helps Colin get dressed in the morning.

Arianne Campbell makes breakfast, including pancakes, for Colin, her son, and Siordia. “Arianne is very professional, and I am very lucky that my life and space are protected,” Siordia told me. “For others, bringing a live-in caregiver, sometimes boundaries can be overstepped. Personal rights should be a given.”

Siordia and Campbell eat together after Colin has finished his meal.

Siordia gets ready to take Colin out to play with his basketball.

Colin and Siordia play with a basketball in the hallway of their apartment complex in the morning. Originally, Siordia had planned to be a nanny and then saw an opportunity to work for Arianne Campbell. “It was a big new step for me that worked out,” she says.

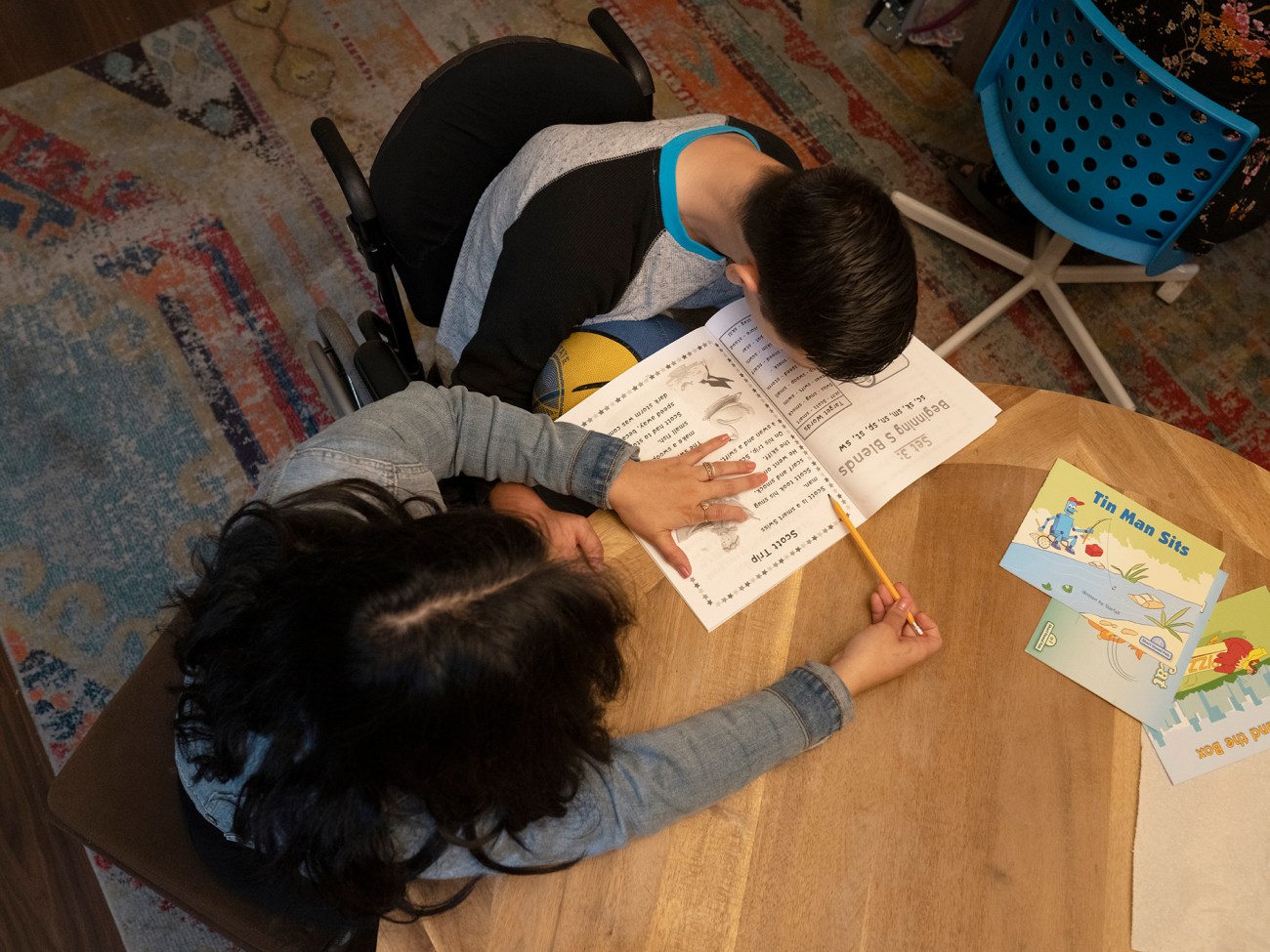

Colin and Siordia work on reading skills.

Arianne shows Colin what is coming up for the week on his wall calendar.

Vivian Siordia at home.

Care worker Liezl Japona gives Dr. Irene Goldenberg her first round of medications for the day at her home in Los Angeles. Japona is affiliated with Hand in Hand, a national group of employers of nannies, house cleaners, and home attendants advocating for better labor practices and affordable, accessible homecare, both in solidarity with workers. The National Domestic Workers Alliance, California Domestic Workers Coalition, and others have also sought to change the state of play.

Japona has worked as a caregiver for 23 years—18 in the Middle East and five in the United States. She spends time talking with Dr. Irene after her first round of medications.

Japona does the dishes after preparing breakfast for Dr. Irene.

Japona picks out clothing options for Dr. Irene. Currently, Japona works only 15 hours a week.

Japona helps Dr. Irene put on jewelry for the day after helping her get dressed.

Japona waits for Dr. Irene to come down the stairs and prepares her walker.

Japona does laundry for Dr. Irene.

Care worker Liezl Japona at her home.

Update, April 11: This article has been updated to more clearly reflect the work of the National Domestic Workers Alliance and California Domestic Workers Coalition.