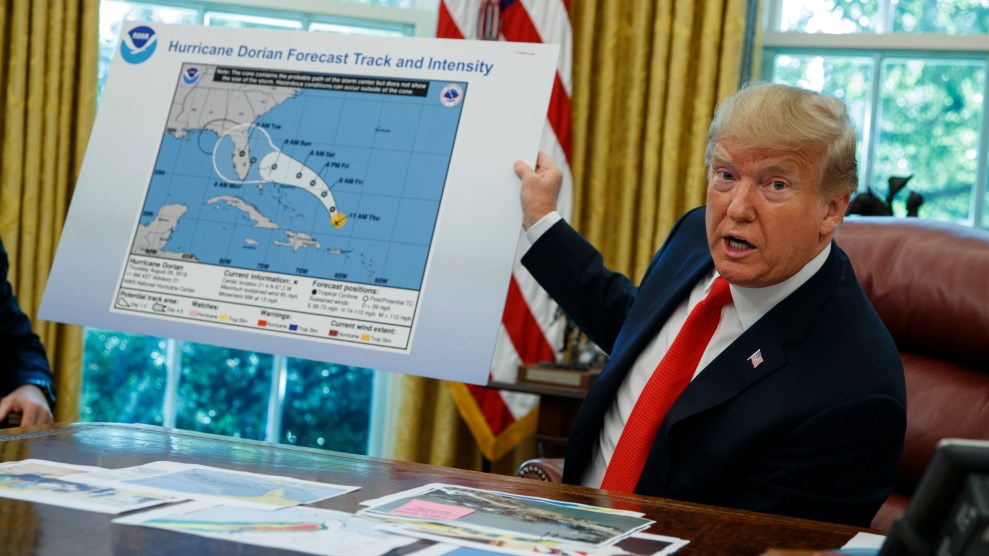

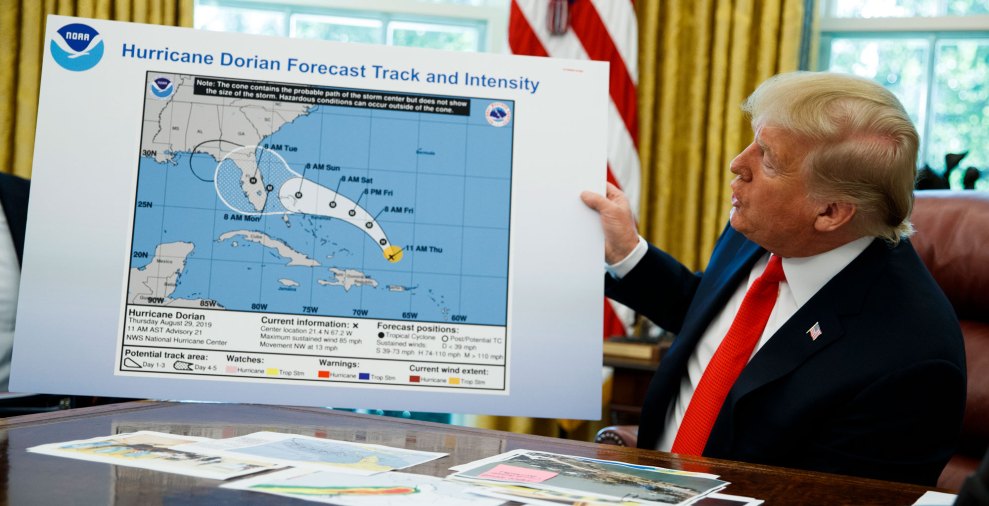

Then-President Donald Trump shows reporters a Sharpie-altered NOAA hurricane forecast on September 4, 2019.Evan Vucci/AP

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Climate experts fear Donald Trump will follow a blueprint created by his allies to gut the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), disbanding its work on climate science and tailoring its operations to business interests.

Joe Biden’s presidency has increased the profile of the science-based federal agency but its future has been put in doubt if Trump wins a second term and at a time when climate impacts continue to worsen.

The plan to “break up NOAA is laid out in the Project 2025 document written by more than 350 right-wingers and helmed by the Heritage Foundation. Called the “Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise,” it is meant to guide the first 180 days of presidency for an incoming Republican president.

The document bears the fingerprints of Trump allies, including Johnny McEntee, who was one of Trump’s closest aides and is a senior adviser to Project 2025. “The National Oceanographic [sic] and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) should be dismantled and many of its functions eliminated, sent to other agencies, privatized, or placed under the control of states and territories,” the proposal says.

That’s a sign that the far right has “no interest in climate truth,” said Chris Gloninger, who last year left his job as a meteorologist in Iowa after receiving death threats over his spotlighting of global warming.

The guidebook chapter detailing the strategy, which was recently spotlighted by E&E News, describes NOAA as a “colossal operation that has become one of the main drivers of the climate change alarm industry and, as such, is harmful to future US prosperity.” It was written by Thomas Gilman, a former Chrysler executive who during Trump’s presidency was chief financial officer for NOAA’s parent body, the commerce department.

Gilman writes that one of NOAAs six main offices, the Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, should be “disbanded” because it issues “theoretical” science and is “the source of much of NOAA’s climate alarmism.” Though he admits it serves “important public safety and business functions as well as academic functions,” Gilman says data from the National Hurricane Center must be “presented neutrally, without adjustments intended to support any one side in the climate debate.”

But NOAA’s research and data are “largely neutral right now,” said Andrew Rosenberg, a former NOAA official who is now a fellow at the University of New Hampshire. “It in fact basically reports the science as the scientific evidence accumulates and has been quite cautious about reporting climate effects,” he said. “It’s not pushing some agenda.”

The rhetoric harkens back to the Trump administration’s scrubbing of climate crisis-related webpages from government websites and stifling climate scientists, said Gloninger, who now works at an environmental consulting firm, the Woods Hole Group.

“It’s one of those things where it seems like if you stop talking about climate change, I think that they truly believe it will just go away,” he said. “They say this term ‘climate alarmism’…and well, the existential crisis of our lifetime is alarming.”

NOAA also houses the National Weather Service (NWS), which provides weather and climate forecasts and warnings. Gilman calls for the service to “fully commercialize its forecasting operations.”

He goes on to say that Americans are already reliant on private weather forecasters, specifically naming AccuWeather and citing a PR release issued by the company to claim that “studies have found that the forecasts and warnings provided by the private companies are more reliable” than the public sector’s. (The mention is noteworthy as Trump once tapped the former CEO of AccuWeather to lead NOAA, though his nomination was soon withdrawn.)

The claims come amid years of attempts from US conservatives to help private companies enter the forecasting arena—proposals that are “nonsense,” said Rosenberg.

Right now, all people can access high-quality forecasts for free through the NWS. But if forecasts were conducted only by private companies that have a profit motive, crucial programming might no longer be available to those in whom business executives don’t see value, said Rosenberg.

“What about air-quality forecasts in underserved communities? What about forecasts available to farmers that aren’t wealthy farmers? Storm-surge forecasts in communities that aren’t wealthy?” he said. “The frontlines of most of climate change are Black and brown communities that have less resources. Are they going to be getting the same service?”

Private companies like Google, thanks to technological advancements in artificial intelligence, may now indeed be producing more accurate forecasts, said Andrew Blum, author of the 2019 book The Weather Machine: A Journey Inside the Forecast. Those private forecasts, however, are all built on NOAA’s data and resources.

Fully privatizing forecasting could also threaten the accuracy of forecasts, said Gloninger, who pointed to AccuWeather’s well-known 30- and 60-day forecasts as one example. Analysts have found that these forecasts are only right about half the time, since peer-reviewed research has found that there is an eight- to 10-day limit on the accuracy of forecasts.

“You can say it’s going to be 75 degrees out on May 15, but we’re not at that ability right now in meteorology,” said Gloninger. Privatizing forecasting could incentivize readings even further into the future to increase views and profits, he said.

Commercializing weather forecasts—an “amazing example of intergovernmental, American-led, postwar, technological achievement”—would also betray the very spirit of the endeavor, said Blum.

In the post-second world war era, John F. Kennedy called for a global weather-forecasting system that relied on unprecedented levels of scientific exchange. A privatized system could potentially stymie the exchange of weather data among countries, yielding less accurate results.

The founding of weather forecasting itself showcases the danger of giving profit-driven companies control, said Rosenberg. When British Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy first introduced Britain to the concept of forecasts during Victorian times, he was often bitterly attacked by business interests. The reason: workers were unwilling to risk their lives when they knew dangerous weather was on the horizon.

“The ship owners said, well, that means maybe I lost a day’s income because the fishermen wouldn’t go out and risk their lives when there was a forecast that was really bad, so they didn’t want a forecast that would give them a day’s warning,” Rosenberg said. “The profit motive ended up trying to push people to do things that were dangerous…There’s a lesson there.”