Eric Lee/ZUMA; mpi34/MediaPunch /IPX

Conservative Supreme Court justices on Tuesday questioned the Justice Department’s use of a 2002 statute against obstructing an official proceeding to prosecute a number of people involved in the January 6 attack on Congress. In pressing Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar on how broadly the DOJ can apply the law, several justices offered similar hypotheticals.

“Would a heckler in today’s audience qualify?” Justice Neil Gorsuch asked.

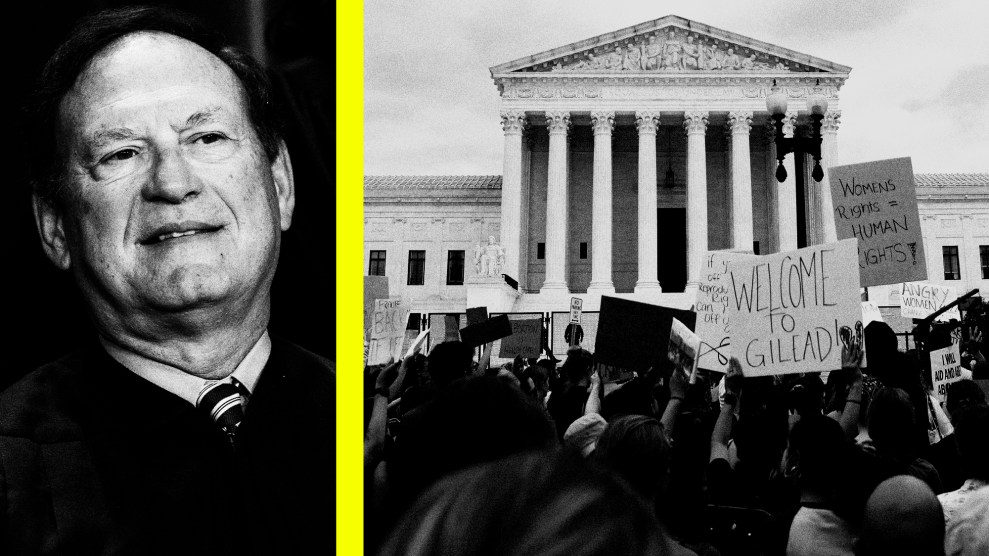

“Why has no one been charged for disrupting the Supreme Court?”

“For all the protests that have occurred in this Court, the Justice Department has not charged any serious offenses,” Justice Samuel Alito said. Alito seemed to be referring to protests that briefly disrupted high court hearings related to the court’s 2022 Dobbs ruling overturning abortion rights. He asked: “Why isn’t that a violation” of the obstruction statute?

Alito’s question led Prelogar to assert that peaceful protesters who cause only brief interruptions of government proceedings would likely not be prosecutable under the obstruction law, in part because the government would struggle to prove they had “corrupt intent”—a requirement of the statute. In contrast, violent protesters appear to have demonstrated their intention of attempting to help a defeated presidential candidate remain in power.

It’s “a fundamentally different posture than if they had stormed into this courtroom, overrun the Supreme Court Police, required the justices and other participants to flee for their safety,” Prelogar said.

Alito acknowledged, “What happened on January 6 was very, very serious, and I’m not equating this with that.” But, he continued, “We need to find out what are the outer reaches of this statute under your interpretation.”

The case turns on a federal statute enacted in 2002 after the Enron accounting scandal that prohibits obstructing a federal proceeding. Since January 6, federal prosecutors have charged hundreds of people involved in the attack on Congress with violating the law, drawing challenges from lawyers for many of those clients.

The petitioner in the case, Joseph Fischer, is a former police officer who joined in the January 6 attack. The prosecution charges that Fischer breached the Capitol building with the crowd, yelling “Charge!” and rushed toward a police line. His attorney argues that Congress intended the obstruction law to apply only to instances where defendants tampered with physical evidence, such as destroying or forging documents used in proceedings. The statute does not apply, however, to more general plans to stop a hearing or other government proceeding from taking place.

A ruling in Fischer’s favor could disrupt the convictions of about 350 January 6 attackers, whom DOJ has successfully prosecuted under the obstruction law. A total of approximately 1,350 people have been charged with crimes related to their actions in the insurrection.

A favorable ruling could also eliminate two of the four criminal charges Special Counsel Jack Smith brought last year against former president Donald Trump. Smith argues that his obstruction charges against Trump would stand even if the high court narrows the application of the law. That’s because Trump’s effort to create slates of fake presidential electors to help him retain power, Smith says, is an example of falsifying evidence, a point that even Fischer’s lawyer concedes falls under the statute.

The Supreme Court has also agreed to separately consider Trump’s long-shot claim that he has “absolute immunity” from any prosecution. By finally agreeing to hear the case, the court has likely delayed Trump’s federal trial on charges of conspiring to overthrow the 2020 election. Many argue this delay may prove to be hugely beneficial to the former president and current GOP presidential nominee.

Notably multiple justices used hypotheticals that suggested some sympathy for the extremist arguments that DOJ is acting unfairly by prosecuting the January 6 attackers with more vigor than they have used against left-leaning demonstrators. These lines of questioning seemed to reveal general skepticism among the court’s conservative majority about the obstruction statute.

Even so, it’s still not clear how the high court will rule in the obstruction case. Much of Tuesday’s argument revolved around the interpretation of the single word “otherwise,” which connects two provisions in the statute. The first makes it illegal to corruptly alter, destroy, or conceal evidence to undermine official proceedings. The second provision says it is a crime “otherwise” to corruptly obstruct, influence, or impede any official proceeding.

Fischer argues that “otherwise” limits the second provision to apply only to evidence. DOJ says the word is part of a “classic catch-all.” That is to say that Congress intended that the second provision should be applied independently and broadly with reference to any efforts made to stop courts or lawmakers from doing their jobs.

A straightforward reading of the statute, Prelogar said, shows Fischer and others violated it on January 6. “Many crimes occurred that day,” she said. “But in plain English, the fundamental wrong committed by many of the rioters, including the petitioner, was a deliberate attempt to stop the joint session of Congress from certifying the results of the election.”