Mother Jones; Maher Attar/Sygma/Getty; AP; New York Times

Beirut was the place to be if you were an action-junkie journalist in the 1980s. Civil War. Militias, the PLO, an Israeli invasion, the occupation of Lebanon. Car Bombings. Truck bombings. And more.

It was an exotic city with an ancient corniche winding along the Mediterranean to the snow-capped Shouf mountains some 30 miles away. Driving through the cedars of Lebanon was glorious. But behind the postcard facade, it was deadly, and dangerous, and cruel.

Everything that was happening there had been festering for centuries, sometimes exploding into bloodshed. Journalists like Terry Anderson, who died over the weekend, were drawn to it, addicted to the action of it, and would not have been anywhere else.

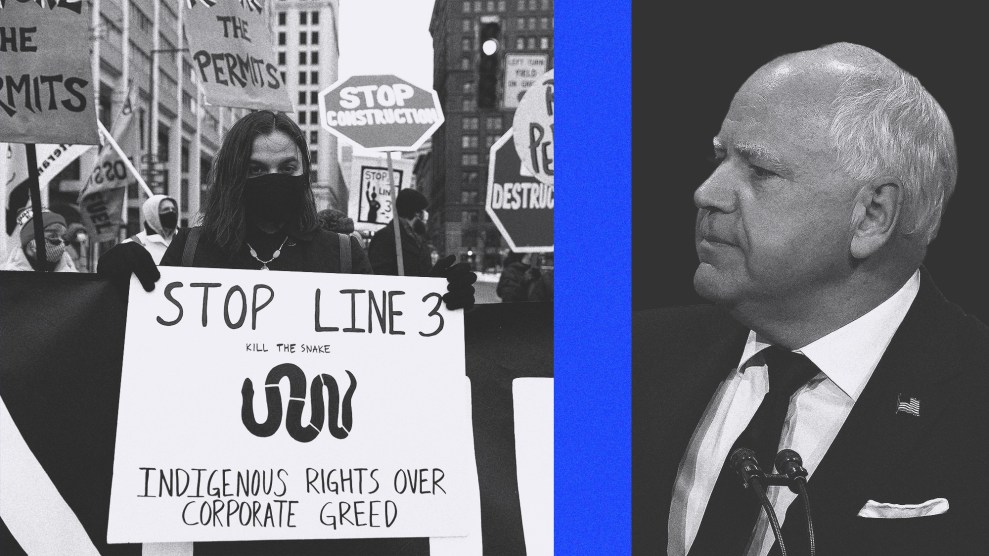

Anderson was no stranger to action. After graduating from high school, he enlisted in the Marine Corps and experienced combat in Vietnam. He went to journalism school after that and was a veteran Associated Press correspondent when he was kidnapped in March 1985 by Hezbollah. He was finally released more than six years later. He was neither the first nor the last hostage taken by Islamic militants during that time. But he became a global figure, a pawn in a nasty game, and a symbol and hero for many journalists and others. And he suffered.

I reported out of Beirut from 1982 to 1984. At that time, I was the Africa correspondent for the Philadelphia Inquirer. After a US-brokered truce between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization collapsed in June 1982, I was sent from Nairobi to Lebanon. I had recently survived my own ordeal as a prisoner the month before. I was reporting on a rampage by the Ugandan army and the slaughter of thousands of Ugandan civilians following the ouster of the dictator Idi Amin. The overthrow of his regime led to a civil war. The army did not want their atrocities disclosed, so they took me prisoner. I was freed three days later, after the Reagan administration demanded that I be released.

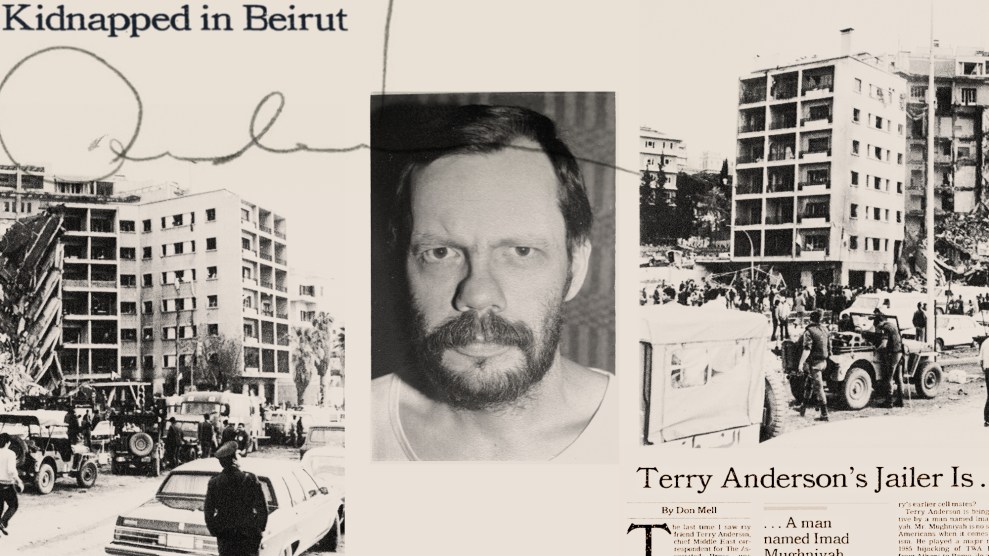

A year later, in Beirut, I would see Terry, stocky and intense, on the streets and at the scenes of horrendous car bombings, or in the midst of firefights when journalists would be drawn to the pulsing throb of automatic weapons and the shriek of rockets and artillery shells. We were not friends but competitors playing a game, where we all knew the stakes, the danger, and the risks. Somehow we loved it.

I recall Terry jumping out of a big American car, binoculars around his neck, notebook in hand. Our Lebanese drivers and fixers—mine drove a big four-door white Mercedes—were always screaming to get the hell back in the car and leave whatever uncontrollable incident we wanted to report on. No internet then, no PTSD awareness, just the thrill of being the storyteller, the witness, the correspondent who hopefully could humanize war by talking with the innocent victims as well as the killers from all sides.

Terry Anderson leaves the US ambassador’s residence in Damascus in 1991 with his 6-year-old daughter Sulome en route to Frankfurt. It was the first meeting between Anderson, who was freed by his captors in Beirut after nearly seven years in captivity, and his daughter.

Santiago Lyon/AP

Imagine you live in a city divided and controlled by five or six militias. No traffic lights work, you somehow have to wrangle passes and the paperwork to travel through checkpoints manned by dead-eyed, grim men, many just boys who knew only war and violence. They know that their superiors often want to talk to the journalists with the passes and they let you through. But the sense of security and safety those paper press passes give you is fragile and not real.

Terry Anderson roamed that city. We all knew any one of us could be kidnapped, or catch a sniper’s bullet, or be stuck in a traffic jam, and that every car around you might explode at any second.

The Inquirer had an apartment in the old and upscale neighborhood called Ras Beirut. From its balcony, I could see the Mediterranean and the remains of the American Embassy that had been blown up by a truck bomb six months before. It had five or six stories and there was a bronze plaque at the entryway proudly proclaiming this was The Reporters Building. The New York Times had an apartment there and so did the Inquirer. Its owner had one of those velvet paintings of Ronald Reagan on his wall. Really.

I filed stories on a telex machine—Google it—and, one night, when the power was out across the city and I had to file my story, I went to the one place where I knew I could: The Commodore Hotel, where many journalists also stayed. Its bar was “the bar” and it had generators. Its telex worked.

A city in a war with no lights or power at night is oppressively still, with silence that has weight. With every step you can hear your heart beating with fear. But I started the 20-minute walk because I had to file my story. That’s why I was there. It was why Terry was there. We were there to tell the story of war.

The Commodore was a dank, musty hotel, surrounded by two layers of parallel-parked cars that were supposed to slow a truck or car bomb or force that bomb to explode before it reached the lobby. I hated going there. To me the hotel was a big target because all the journalists were there. But at least there was a car barrier to stop a car bomb.

I got there safely, filed, and when I walked back through the winding streets of elegant 19th-century buildings, I heard a car grinding through the streets.

This was not good. I passed near the Saudi Embassy, protected by a thick wall of sandbags and cement and guarded by Lebanese army troops.

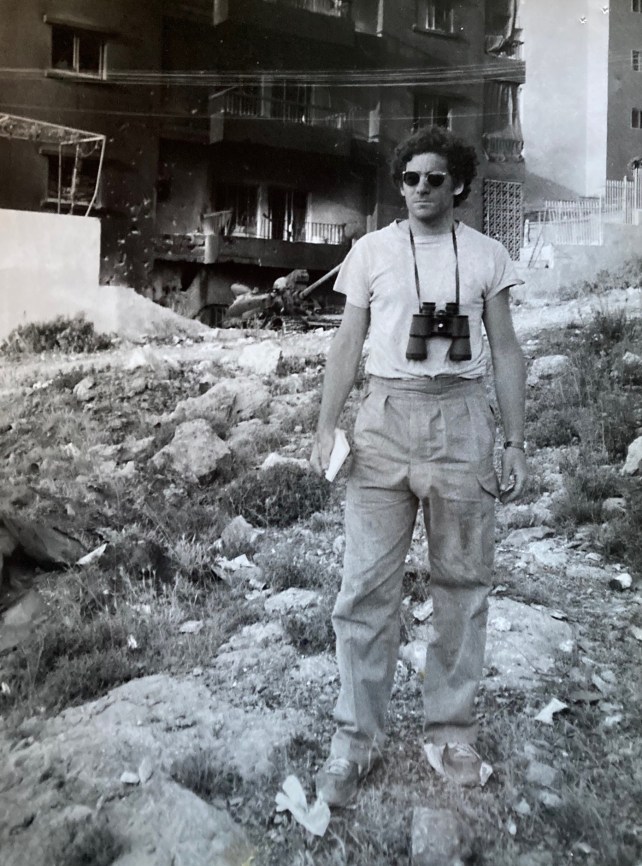

Robert J. Rosenthal in Beirut in the summer of 1982. Behind him sits a burned-out Syrian tank in the rubble of an apartment building both destroyed by an Israeli missile.

Courtesy Robert J. Rosenthal

I heard the car approaching, its headlights found me. The car stopped, and two men jumped out. They pushed me up against a wall, stuck a gun in my left ear, and shouted “Do you speak English?” over and over. I knew what was up. If they wanted to kill me, they easily could have. But they wanted me.

I shook my head and did not speak. They spoke Arabic, arguing, and then I heard shouts and the sound of men running in boots toward us. The two men holding me shoved me violently against the wall, jumped in their car, and sped off.

I exhaled and was about to say thank you when more hands spun me around, jammed me against the wall, spread-eagled, and searched my pockets until they found my press credentials.

A Lebanese army officer leaned in, tuned my head harshly, and looked in my eyes. “You are a fool,” he said in English, “Go home.”

I only had a few blocks to go. I was lucky.

Terry Anderson was not. Eventually, I went back to Africa. Terry stayed on as did many others. To bear witness. To try to write with compassion and empathy, and humanize something that no human should experience. To tell the stories of the victims of war, killed or wounded, and the traumatized survivors. He lost more than six years of his life to that mission.

I know Terry believed that his stories might make a difference. He and the other journalists willing to risk so much to get the story, do so because they believe those stories just might make a difference in a world where making a difference with passion, skill, and truthful storytelling is, and has always been, an honorable thing.