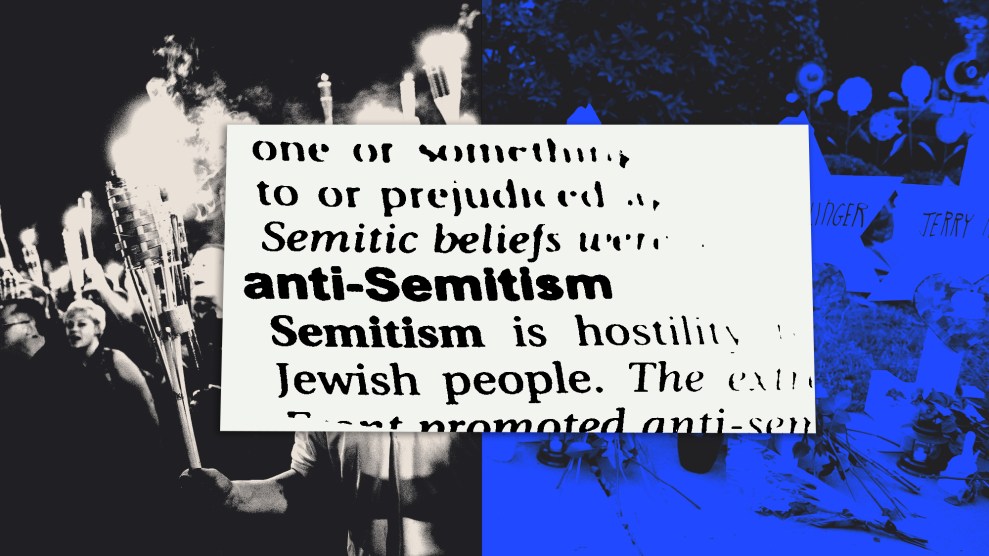

Mother Jones; Samuel Corum/Anadolu Agency/Getty, Jeff Swensen/Getty

“Is it antisemitism or anti-Semitism?” a Mother Jones reporter asked me last week, a question freshly in focus as campus protests grow. It’s been six months since the FBI announced that antisemitism (by any style) is at historic levels, and three years since the Associated Press, the New York Times, and several other news organizations changed “anti-Semitism” to “antisemitism,” or expressed support for the switch. The style debate is effectively settled (lowercase appears to have won, and the hyphen appears to have lost), even as disputes over its definition and prevalence engulf campuses.

But as events unfold, many reporters and editors still wonder whether to capitalize, lowercase, hyphenate, or defer to individual choice. Which is why variation persists across news sites. If this choice clarifies much, it’s how fluid the convention is, and how extensive the need for it, at a time when antisemitic attacks are ascendent. No group faces more religion-based hate crimes in the United States than Jews. The pain it inflicts, and the wounds it deepens, makes debates like this, over small tweaks, both secondary to and a proxy for the larger stakes. Harm reduction, not style, is the point.

But the two debates—over reducing harm and how to style it—share a politics. The evolution of style is driven by much of the same energy that fuels political change. That’s why the historian Deborah Lipstadt, who leads the lowercase movement and is now the US special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism, marked it as a victory when the AP shifted to lowercase: “When you fight prejudice & hatred, you don’t win many battles. But we won this one.”

As Mother Jones’ style guide editor, I’ve followed this debate for years as the lowercase side steadily gained ground, and I’d been something of a resister. I wondered at first whether lowercasing really improves understanding and clears up meaning or is a symbolic step in solidarity to demonstrate awareness of the ravages of antisemitism without firm stylistic footing for the change itself. Methods do matter: It matters whether lowercasing helps people understand more or confuses further. My colleagues and I had been discussing this, and I wasn’t the only one wondering. Ken Jacobson, deputy national director of the Anti-Defamation League, suggested that lowercasing “will not enhance anyone’s understanding and could even undermine” wide recognition that the label “conveys the power of this evil.” But the ADL made the opposite move, announcing “antisemitism” as its default and applauding the AP for following suit.

The newer convention is catching on: “I always write ‘antisemitism’ and most colleagues do as well,” Susannah Heschel, chair of Dartmouth’s Jewish Studies Program, tells me.

“Strong preference for no hyphen, all lowercase,” agrees Kenneth Stern, director of the Bard Center for the Study of Hate.

“We prefer ‘antisemitism’” too, Hara Person, chief executive of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, tells me. Her view is shared by Sharon Brous, the rabbi who blessed Presidents Biden and Obama at inaugural events. “I only use ‘antisemitism,’” Brous says.

“I use ‘antisemitism’” as well, says Omer Bartov, a professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Brown University, “because ‘anti-Semitism’ makes an assumption that there is such an animal as Semitism or Semites.”

I’ve updated our style guide to reflect the newer convention. With one caveat: Many of the concerns with the capitalized letter still linger in lowercase. The root challenge remains.

The movement to lowercase argues that the word “anti-Semitism” is itself antisemitic: The term is pejorative, popularized by bigot Wilhelm Marr in 1879. He claimed that Jews were an alien race and called for their removal from Germany. He wanted a word that would lend his campaign the veneer of sophistication. Judenhass (“Jew-hatred”) was available, but it too readily evoked familiar hate. For his movement to flourish, a euphemism would be helpful.

Lowercasing today is an effort to mitigate that malice by undoing a capitalization born of bigotry. The “Semite” in “anti-Semitism” is not a real religious or ethnic or linguistic group—it is simply a slur for Marr’s Jews. And once “S” goes down, the basic rules of punctuation mean the hyphen drops. That much I get. It’s a coherent view of etymology, of where the word comes from. But it appears to underestimate how the label has evolved, and where it’s come to.

By any style, the meaning is unmistakable: prejudice against Jews. Objections are made that “Semite” falsely creates a group that includes non-Jews among speakers of a set of languages. Obfuscators gladly tout that technicality to gloss over anti-Jewish hate by pointing out that non-Jewish Arabs are “Semites” too. But the term “has never popularly referred to Arabs or other ‘Semites,’” as Yair Rosenberg points out in the Atlantic.

Lowercase advocates argue that the change adds clarity: The ADL says “this slight alteration will help to clarify understanding of this age-old hatred.” So too argues the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, citing “clarity.” I share their goal, but I struggled at first with their method: If meaning were unclear, why merely lowercase as if clarifying? The word is either functionally clear or isn’t, and it becomes no clearer lowercase; we’re still left with the root confusion. Lowercasing enshrines it further, naturalizing the misnomer by turning it into a common noun that conceals, rather than corrects, its constructed origins. At least capitalization has the benefit of calling attention to itself as a construct.

At the heart of this choice is a debate not about clarity, but about how to reduce harm. Much of the advocacy for lowercase—and the reason I’ve switched—has less to do with letters than with the profound anguish and animus many Jews navigate. We are hated throughout history, acutely so today: accused of conspiracies to control and oppress; of being too white by the far left and not white enough by the far right—despite the fact that millions of Jews are not white and do not neatly fit familiar codes of color. “Semite” is a category created to be hated. The move to lowercase is a move to demote its derogatory power.

This choice is small, but the stakes are big. The US ambassador Lipstadt sees lowercasing as part of fighting prejudice. She says the capitalized convention “completely distorts the meaning of the word.” She isn’t the only historian who takes a hard line on lowercase. Some historians find hatred in the hyphen itself: “One could argue that spelling the word with a hyphen is not only incorrect, but that [it] is in itself a demonstration of Judeophobia,” Aaron Breitbart, senior researcher at the human rights organization Wiesenthal Center, tells me.

Judeophobia? In a hyphen? This, to me, is a stretch; it ascribes to punctuation what is better ascribed to attitudes in society, scripture, and culture. Finding hatred in a grammatical device, one widely used by millions of people without a trace of malice or misunderstanding, is an analysis that overstuffs syntax with political imperative.

A practical approach is available: Use “antisemitism” (or “anti-Semitism”) interchangeably with “Jew-hatred” or “anti-Jewish bigotry,” shifting away from the misnomer entirely. “At this point I suspect ‘Jew-hatred’ would be more universally clear” than “antisemitism,” David Wolpe, a Harvard Divinity School scholar and rabbi, tells me.

But the term “Jew-hatred” has a popularity problem: The vast majority of American Jews don’t favor it and instead prefer the word “antisemitism,” according to the unpublished results of a 2021 survey shared with me by the American Jewish Committee’s US director for combating antisemitism, Holly Huffnagle, formerly a Department of State adviser. She tells me 73 percent of American Jews say they prefer the word “antisemitism” to “Jew-hatred,” and only 14 percent prefer the term “Jew-hatred.”

This preference could be because “antisemitism” evokes the nature of this hatred: the winking way it euphemizes; the distinct attempt to make palatable what is too plain in “Jew-hatred.”

But the preference is clear: The word “antisemitism” is favored over “Jew-hatred.” The misnomer has evolved.

Usage changes for complex reasons. The strongest argument I’ve heard for lowercase makes a deeper point than anything technical: All words are contrivances. When one is so misclassifying, weaponized, and misconstrued, it is worth trying to turn it around and hit reset.

As hatred rises, we’ll continue to see headlines move fluidly between “anti-Semitism” and “antisemitism.” And that’s fine. You are not behind the curve, or the culture, if you aren’t sure which to use. I suspect that, like me, most readers care more about practical meaning, and revelatory investigations, than blanket or compelled consistency. Let me know your thoughts at styleguide@motherjones.com, or below: