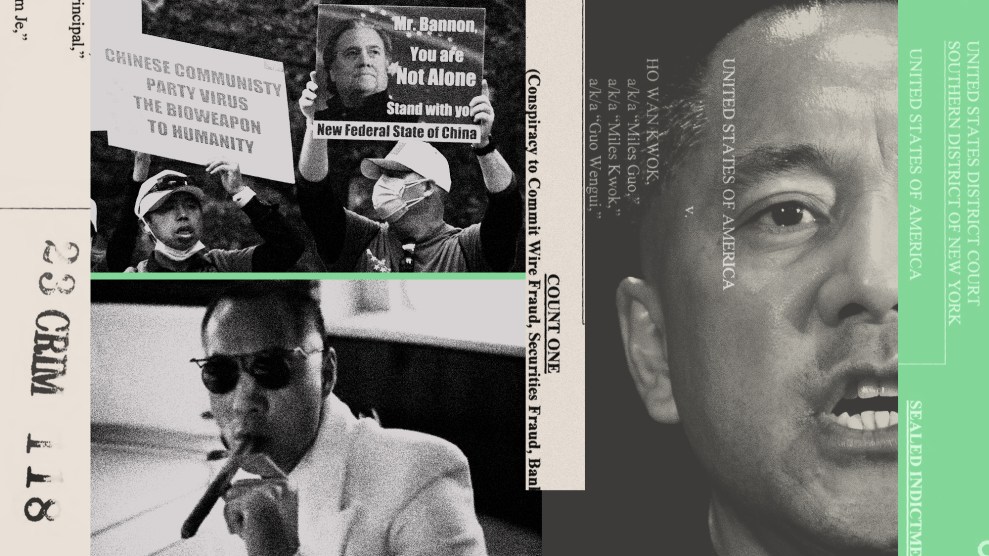

Mother Jones; Don Emmert/AFP/Getty; Anthony Behar/Sipa/AP; YouTube

In 2017, the exiled Chinese mogul Guo Wengui began to remake himself in America as a dissident celebrity. In media appearances, tweets, and lengthy YouTube videos, Guo launched tirades against Chinese Communist Party corruption. They made him famous among extremely online Chinese emigres and won him prominence as an ally of Steve Bannon and other Trumpworld luminaries.

Guo sold a brand: A mega-rich, Brioni-clad, rule-breaking Bannon buddy leading a “whistleblower movement” with an audacious goal to “take down the CCP” and install his own supposed government-in-waiting in Beijing.

But the truth of Guo’s story is now at issue in the federal courthouse in Manhattan, where he stands trial for fraud and money laundering. In an opening statement Friday, Assistant US Attorney Micah Fergenson previewed evidence he said shows that Guo—who has also used the names Ho Wan Kwok and Miles Guo—stole more than $1 billion from his own ardent fans who invested in scam financial ventures Guo launched in 2020 and 2021.

“Miles Guo ran a simple con on a grand scale,” Fergenson said. “He lived a billionaire’s lifestyle using money he stole from people he tricked and cheated.”

Prosecutors argue Guo’s whole shtick is bogus – that he is neither a real dissident or really rich. Fergenson suggested on Friday that Guo’s movement and complaints against the CCP are, instead, a story he created to win the trust of followers before fleecing them.

And while the mogul did become wildly wealthy as a Chinese real estate developer before fleeing to the US in 2015, Fergenson said he was short on cash funds after the Chinese and Hong Kong governments seized most of his assets in 2018. That was “shortly before the scheme began,” Fergenson said. “The defendant needed money.”

Prosecutors allege Guo’s criminal conspiracy started in 2018, when he launched, with Bannon at his side, two nonprofits supposedly aimed at exposing corruption in China.

Guo’s attorney Sabrina Shroff said in her opening statement that Guo’s political movement was in earnest—the “essence of his entire being.” His financial ventures were not only real businesses but legitimate parts of a grand plan to fight the CCP, she said.

“It was not a bet,” Shroff said. “It was not a scheme. It was not a con.”

Prosecutors charge that Guo’s fraud was carried out via four interrelated investment projects. He collected hundreds of millions of dollars for a media company called GTV. When the SEC effectively blocked that “private offering,” Guo continued to collect cash by offering followers in hundreds of online fan clubs he called “farms” the chance to offer him “loans” that would result in their receiving GTV stock. Guo then formed a G|CLUBS, a supposed “concierge service” where annual fees of $10,000 to $50,000 offered members nothing but the chance to invest, again, in other Guo ventures.

Another scheme involved cryptocurrency in which Guo solicited investments with outlandish and, prosecutors say, completely false claims, among them a made up assertion that the currency was 20 percent backed by gold.

Guo said all these ventures were part of his war on the CCP and repeatedly assured investors that he would guarantee they made money. “These were lies” Fergenson said.

Guo used these funds, prosecutors said, to maintain the lifestyle of a supposed billionaire, purchasing items like a $2 million Bugatti, a $4 million Ferrari for his son, a $4 million mansion, a $35,000 mattress and a $65,000 TV.

The Chinese diaspora investors who Guo, and Bannon, claimed to champion were left high and dry, unable to recover savings they had trusted Guo with, Fergenson argued.

Shroff did not dwell on the details of Guo’s financial ventures. But she described him as a high-level “ideas man” for his businesses. She said the outfits were run largely by two underlings who were also charged in his case: William Je and Yvette Wang. That’s a hint the defense will suggest Guo was unaware of crimes by Wang, who pleaded guilty to wire fraud and money laundering charges last month or Je, a fugitive. (Je has denied wrongdoing via a spokesperson.)

Guo “did not have criminal intent,” Shroff said.

Shroff also said that past Chinese government efforts to secure Guo’s extradition and other CCP harassment helped explain some of his conduct. She argued, for instance, that Chinese agents once wired money into a Guo’s account using names of people sanctioned by the Treasury Department, resulting in a bank freezing Guo’s account. His moving of investors’ money into various accounts he controlled thus could be an effort to avoid CCP harassment, she said.

Shroff faulted prosecutors for highlighting the gaudy details of Guo’s purchases, urging jurors not to convict Guo over “moral judgements” about conspicuous consumption.

Spending tens of thousands of dollars on a G|CLUBS membership, or $800 on anti-vaccine sweatpants sold by a fashion company Guo ran, Shroff said “is a person’s choice, a choice the Chinese government doesn’t want them to have.”

Prosecutors’ allegation that Guo stole from “the movement” he built is illogical, she said, “because he is the movement.”