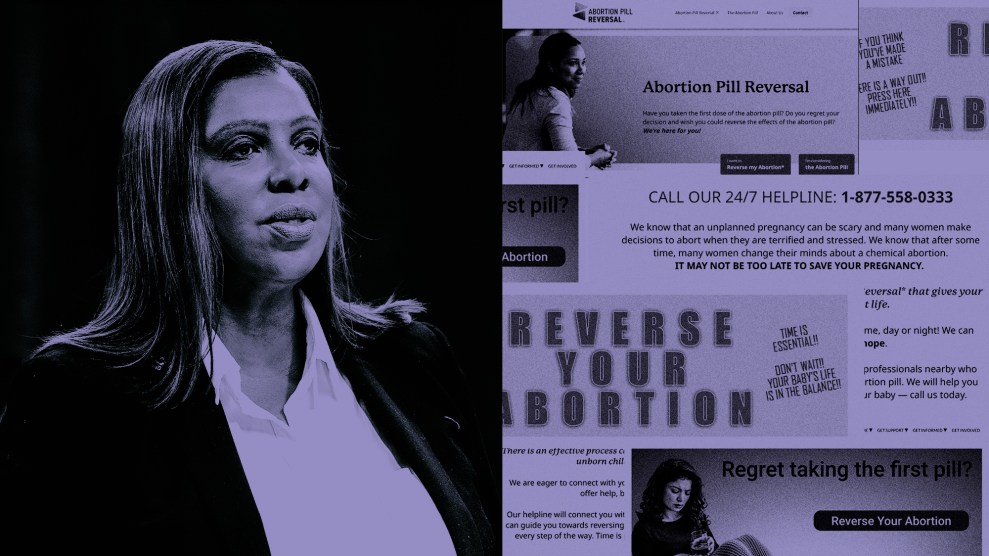

Mother Jones; Lev Radin/Sipa USA/AP

Abortion rights advocates might be surprised to learn that, in deep-blue New York, anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers outnumber abortion clinics.

There are more than 120 such centers (known as CPCs, though they also go by other names) throughout New York, according to a coalition of abortion rights groups in the state, compared to a little more than 100 in-person abortion providers. In places like New York—where abortion is legal through 24 weeks’ gestation, and lawmakers have enacted legislation protecting abortion access—CPCs are particularly insidious: They lure struggling pregnant people in with promises of financial and emotional support, and then actively discourage them from obtaining abortions—often, in part, through medical misinformation delivered mostly by volunteers, not medical professionals. One of their favorite deceptive tactics is to hawk so-called “abortion pill reversal” regimens, which they falsely claim can stop a medication abortion in its tracks, allowing someone to continue a pregnancy.

On Monday, New York State Attorney General Letitia James announced she is suing the anti-abortion group Heartbeat International—which claims to operate more than 3,000 CPCs worldwide—and 11 other CPCs throughout the state for “using false and misleading statements” to “aggressively” advertise the so-called treatment, which involves taking repeated doses of progesterone—a hormone the body produces during pregnancy—after someone has taken mifepristone, the first of the two pills in the medication abortion regimen. (Mifepristone blocks progesterone, and misoprostol, the second pill taken in a medication abortion, expels the pregnancy.) Anti-abortion groups tend to highlight individual stories of people who allegedly followed this advice and were able to continue a pregnancy; they also often emphasize that immediate regret after seeking an abortion in the first place drove them to try to “reverse” that choice—even though research shows most people who obtain abortions ultimately feel it was the right decision.

But as James’ office—and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists—point out, the claims underlying so-called “abortion pill reversal” are unsupported by scientific evidence, and a 2020 study that aimed to examine the safety and efficacy of it was halted early due to safety concerns after three patients experienced severe hemorrhaging. On the other hand, more than 100 published studies have shown that medication abortion is safe and effective, including when the pills are prescribed remotely and mailed to patients—which directly contradicts the false arguments conservatives have taken to the Supreme Court in a bid to drastically restrict access to abortion pills, as I have previously reported.

But none of this stops CPCs from claiming otherwise. James alleges their statements “constitute persistent fraud and illegality…and deceptive business and false advertising practices”; her office wants the court to rule that the CPCs must remove all false and misleading claims from their promotional materials and pay out civil penalties. In a statement, James said that, in light of rising reproductive health restrictions post-Dobbs, “we must protect pregnant people’s right to make safe, well-informed decisions about their health.” Heartbeat International and a group of CPCs are countersuing the AG’s office, alleging that CPCs have been “unfairly singled out…because they offer alternatives to abortion.” The Thomas More Society, the conservative Catholic legal group representing the group pro bono, alleges that the statements that are the subject of the litigation are protected free speech. (Heartbeat does not operate all of the CPCs that James is suing, but those CPCs “all advertise or promote Heartbeat” and abortion pill reversal, according to a spokesperson for the AG’s office.)

The lawsuit is a reminder that abortion opponents will do anything they can to curtail abortion access post-Dobbs—even in places where voters have moved to protect abortion rights, and even if it means perpetrating myths about how and why people get abortions. It also comes as the latest example of a Democratic Attorney General using state law to crack down on CPCs. In March, Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes issued a consumer alert outlining how CPCs “may make misleading statements about the services they provide, or otherwise attempt to deceive patients in medically vulnerable situations.” Last September, California Attorney General Rob Bonta sued Heartbeat International and a chain of five CPCs in the state in a lawsuit that also took aim at their “fraudulent and misleading claims” about so-called abortion pill reversal. And in 2022, New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin, alongside the state Department of Consumer Affairs, announced they were also issuing a consumer alert about CPCs. As a note published in the Cornell Law Review in January points out, state attorneys general are uniquely positioned to take on CPCs given both the broad powers and extensive tools they wield to file lawsuits in the public interest, and their important roles in state governments, particularly post-Dobbs.

Looking at the list of CPCs James is suing, it was jarring to see two located in New York City—one in Brooklyn, and one in Queens. “People think that there’s no, like, real need to advance or end stigma here,” Elizabeth Estrada of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice told the New York Times in a 2022 story about CPCs in the city. “But that’s not true, especially when we’re seeing so many crisis pregnancy centers proliferating.”

Aviva Zadoff, director of advocacy and volunteer engagement at the National Council of Jewish Women New York, which leads a campaign to track CPCs in the state, told me that “these groups have gotten away with spreading disinformation for far too long.” The 2022 Times report provides an example of the consequences, telling the story of a woman who visited a CPC in the Bronx—located across the street from a Planned Parenthood—for advice and wound up continuing her pregnancy, despite her hesitation and financial struggles, after CPC staffers promised her material support. But that never came through, she told the Times: “They would say they know somebody that could probably refer me somewhere, that could help me financially, diapers and stuff like that. But I never received any phone call from anybody.”

These false promises, coupled with medical misinformation, are exactly why CPCs are so dangerous—even in places, like New York, that claim to protect abortion rights.

“When faced with an unplanned pregnancy,” Zadoff said, “everyone is entitled to judgement-free care and honest information.”