iStock / Getty Images

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt signed a bill that will allow courts to shorten the prison sentences of people who can prove they committed their crime because they were experiencing domestic violence—a significant reform in a state that incarcerates many domestic violence survivors for fighting back in self-defense, doing drugs to cope, or failing to protect their kids from the abuse.

Stitt’s decision to approve the Oklahoma Survivors’ Act came last week, after he vetoed a similar bill with the same name in April. Oklahoma has the country’s highest rate of domestic violence per capita and among the highest rates of female incarceration. Under the new law, sentences of life without the possibility of parole could be reduced to 30 years or less; sentences of 30 years or more could be reduced to 20 years or less; and so on.

Incarcerated survivors in Oklahoma cheered the news of the law’s passage, though it came with a catch: To get the governor’s signature, compromise language was inserted into the bill that could make it harder for some of them to shorten their sentences. Bolts reported on the specifics:

The compromise language…raised the burden of proof for those convicted of violent felonies, such as assault, manslaughter, murder, and robbery. To qualify [for resentencing], they must provide documentation that the victim of the crime was also the perpetrator of the defendant’s abuse, the person who trafficked them, or that their action was coerced by their abuser.

Documentation can include trial transcripts, court briefs, law enforcement reports, or other records, according to Colleen McCarty, executive director of the Oklahoma Appleseed Center for Law and Justice, which advocated for the bill.

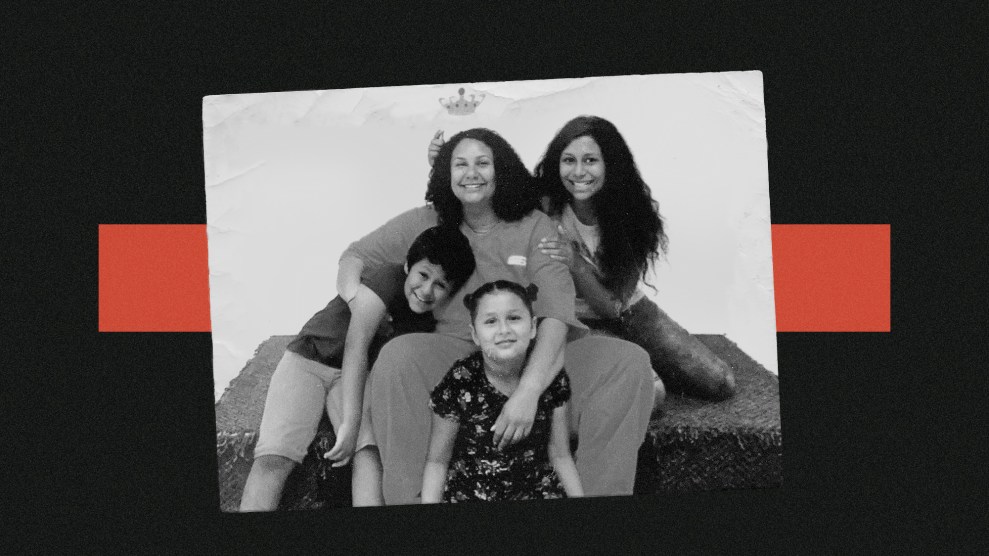

The compromise language could affect survivors who are incarcerated for failing to protect their kids from an abuser, a plight I covered in a Mother Jones investigation. Although many of these survivors committed no violence themselves, “failing to protect” a child is often charged as a violent felony in Oklahoma. As a result, in order to get resentenced under the new law, these survivors will have to prove that they didn’t stop the child abuse because they were coerced by the abuser. Some of them, disproportionately mothers of color, are serving more prison time than the men who harmed them and their kids.

The Oklahoma Survivors’ Act goes into effect in August. McCarty has already identified more than a dozen people whom her organization plans to help with resentencing petitions under the law.