40

ACRES

AND

A LIE

A government program gave formerly enslaved people land after the Civil War, only to take nearly all of it back a year and a half later. We used artificial intelligence to track down the people, places, and stories that had long been misunderstood and forgotten, then asked their descendants about what’s owed now.

A COLLABORATION BETWEEN

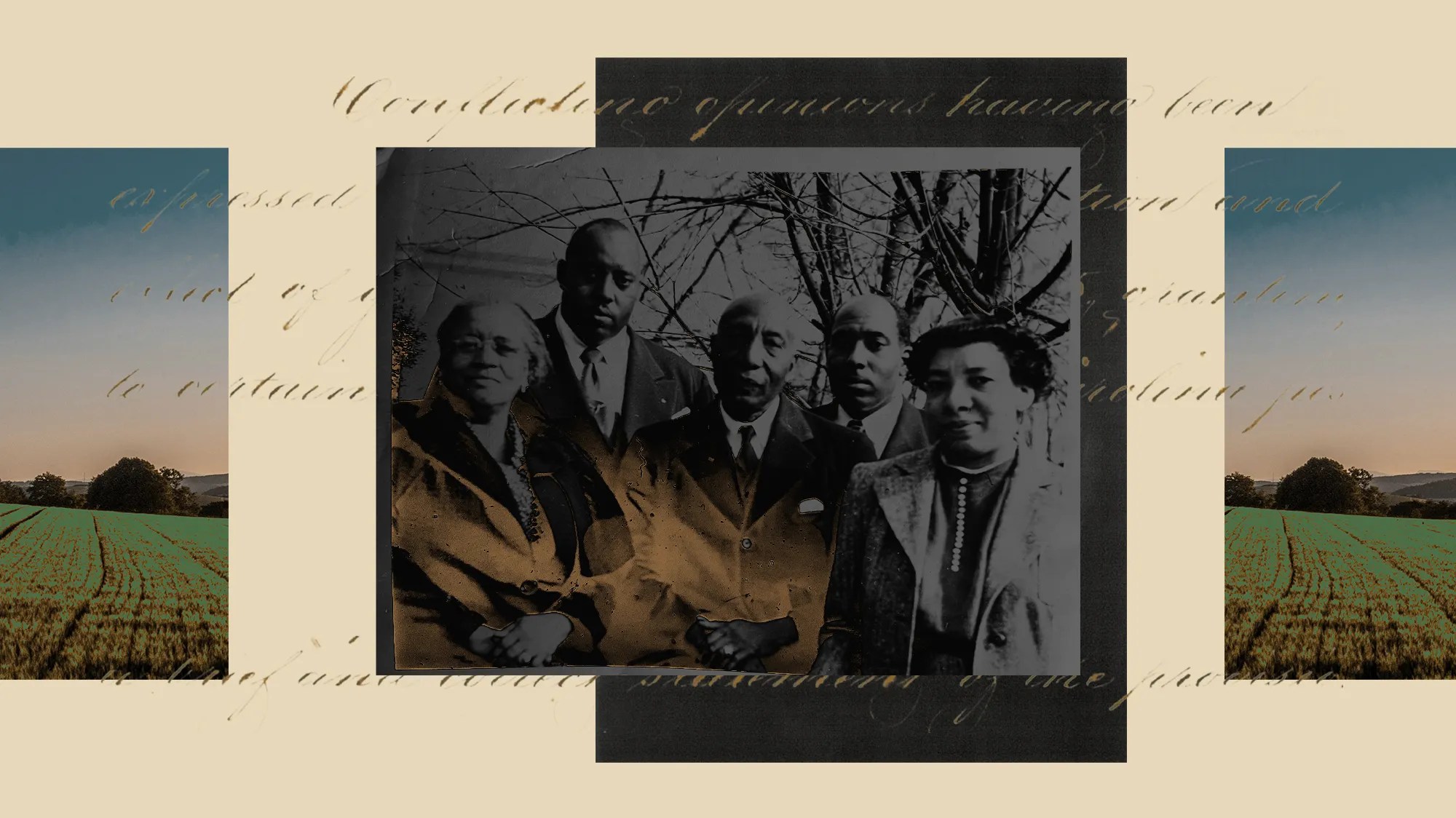

Black Americans have been demanding compensation and restitution for their suffering since the end of the Civil War.

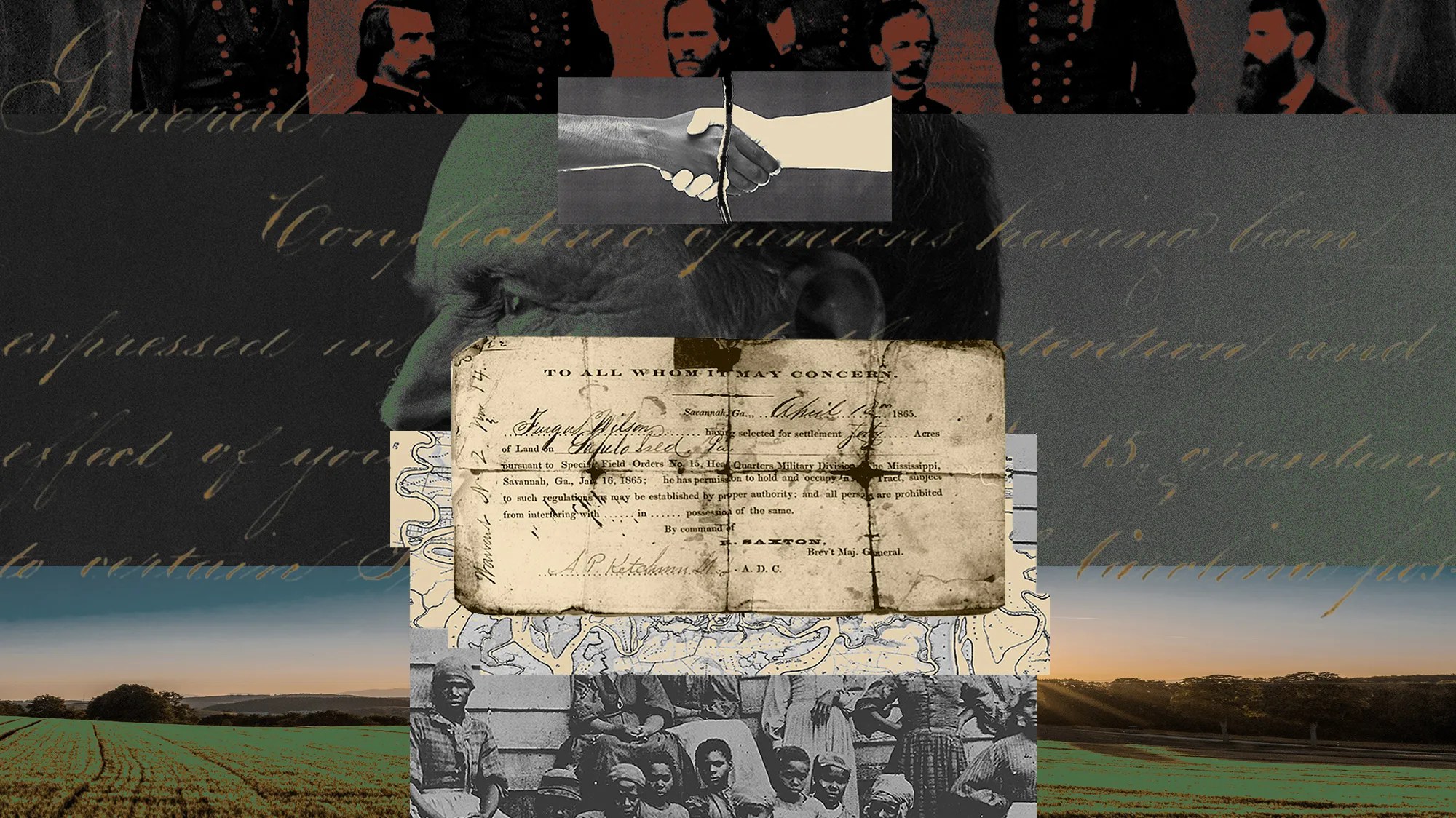

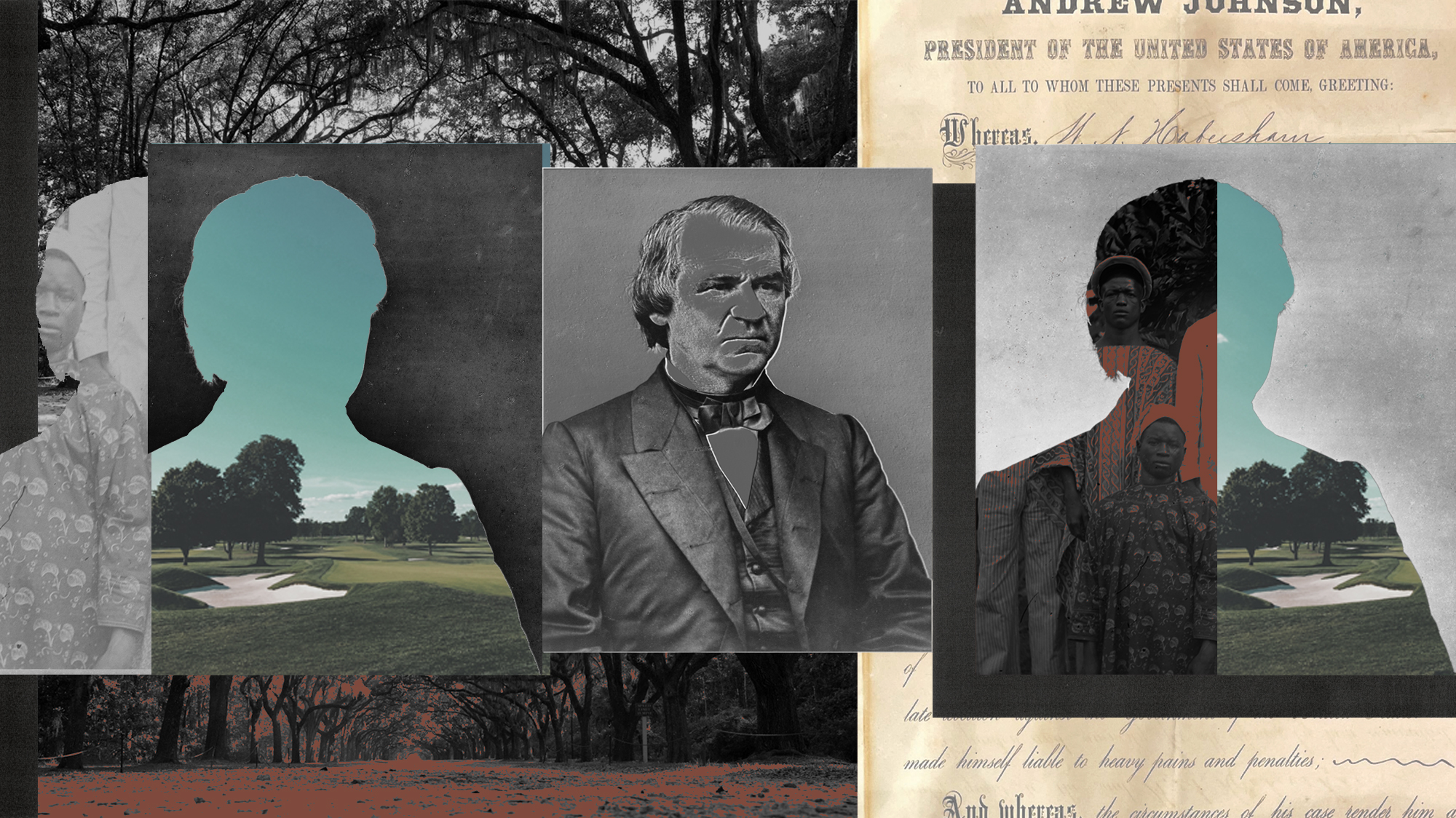

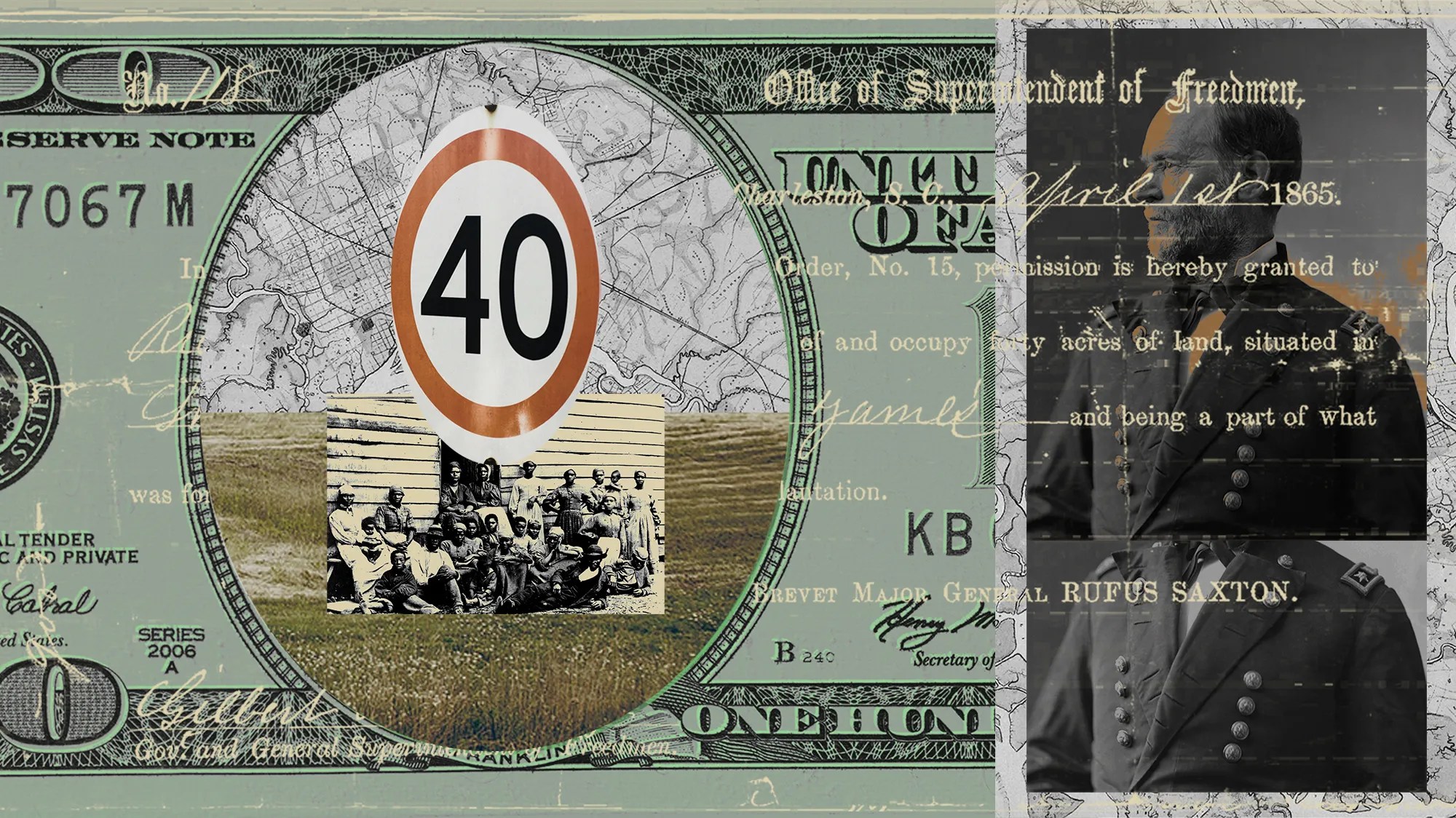

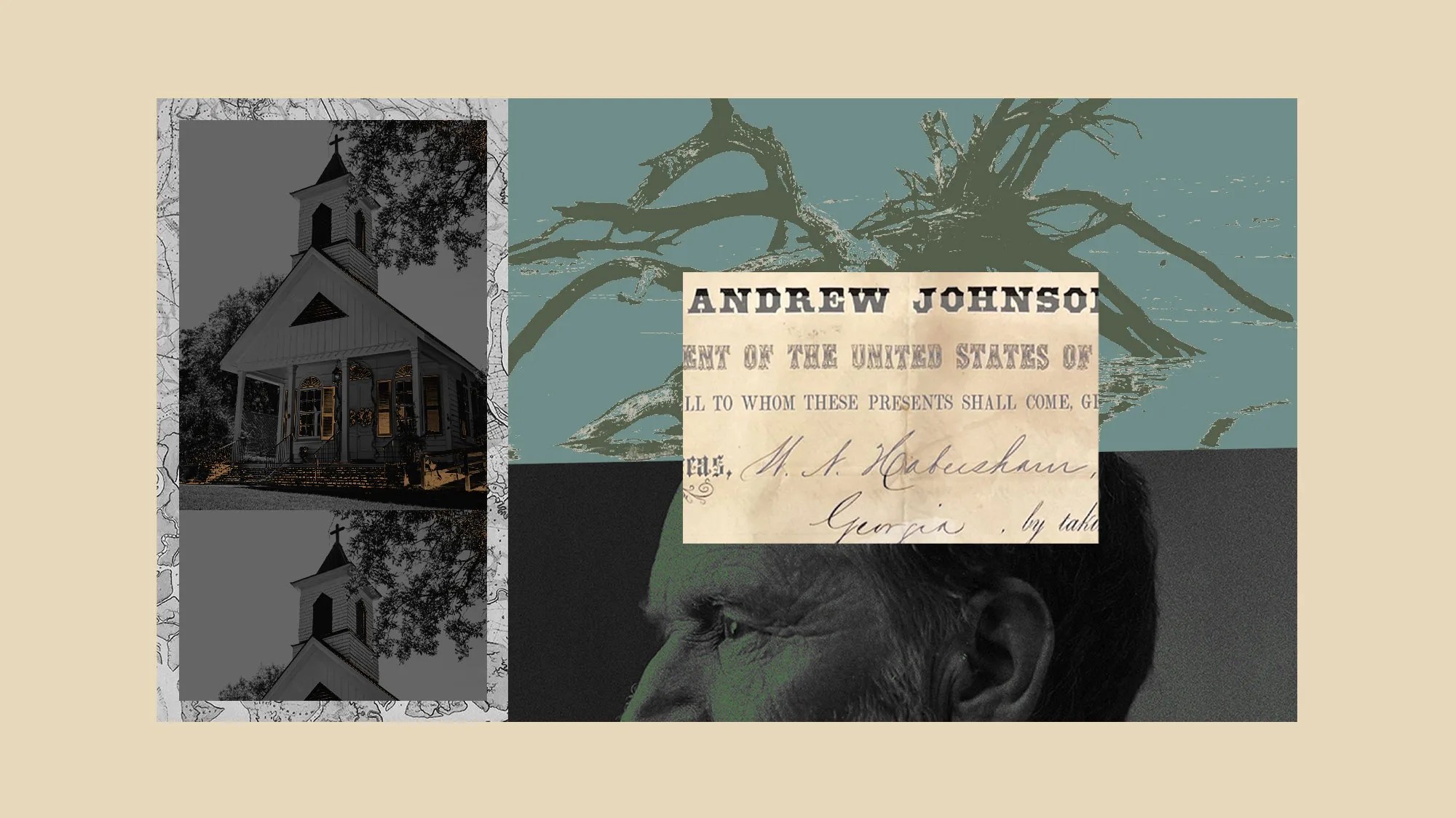

40 Acres and a Mule remains the nation’s most famous attempt to provide some form of reparations for American slavery. Today, it is largely remembered as a broken promise and an abandoned step toward multiracial democracy. Less known is that the federal government actually did issue hundreds, perhaps thousands, of titles to specific plots of land between 4 and 40 acres. Freedmen and women built homes, established local governments, and farmed the land. But their utopia didn’t last long. After President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, his successor, Andrew Johnson, stripped property from formerly enslaved Black residents across the South and returned it to their past enslavers.

Over the course of two and a half years, a team of Public Integrity reporters, editors, and researchers identified 1,250 Black men and women who had earned land as reparations after the Civil War. From there, the team conducted genealogical research to locate living descendants of many of those who had received and then lost the land. For the first time, these living Black Americans were made aware of the specific land that had been given to and then taken away from their ancestors.

This project is an unprecedented and innovative use of Freedmen’s Bureau records—an impossible task for most of American history, until recent advances in genealogical research and the digitization of thousands of pages of Reconstruction-era documents made it feasible.

AUDIO

In our three-part podcast series with the Center for Public Integrity, we explore the legacy of America’s broken promise to formerly enslaved Black people.

40 Acres and a Lie, Part 1

After Jim Hutchinson was freed from slavery in 1865, the federal government gave him a land title: 40 acres on Edisto Island, South Carolina. Soon after, that land was taken back. Through his descendants and the descendants of a former slaveholder, we reveal the truth about 40 Acres and a Mule—and how the federal government’s ultimate betrayal fueled a racial wealth gap that persists today.

40 Acres and a Lie, Part 2

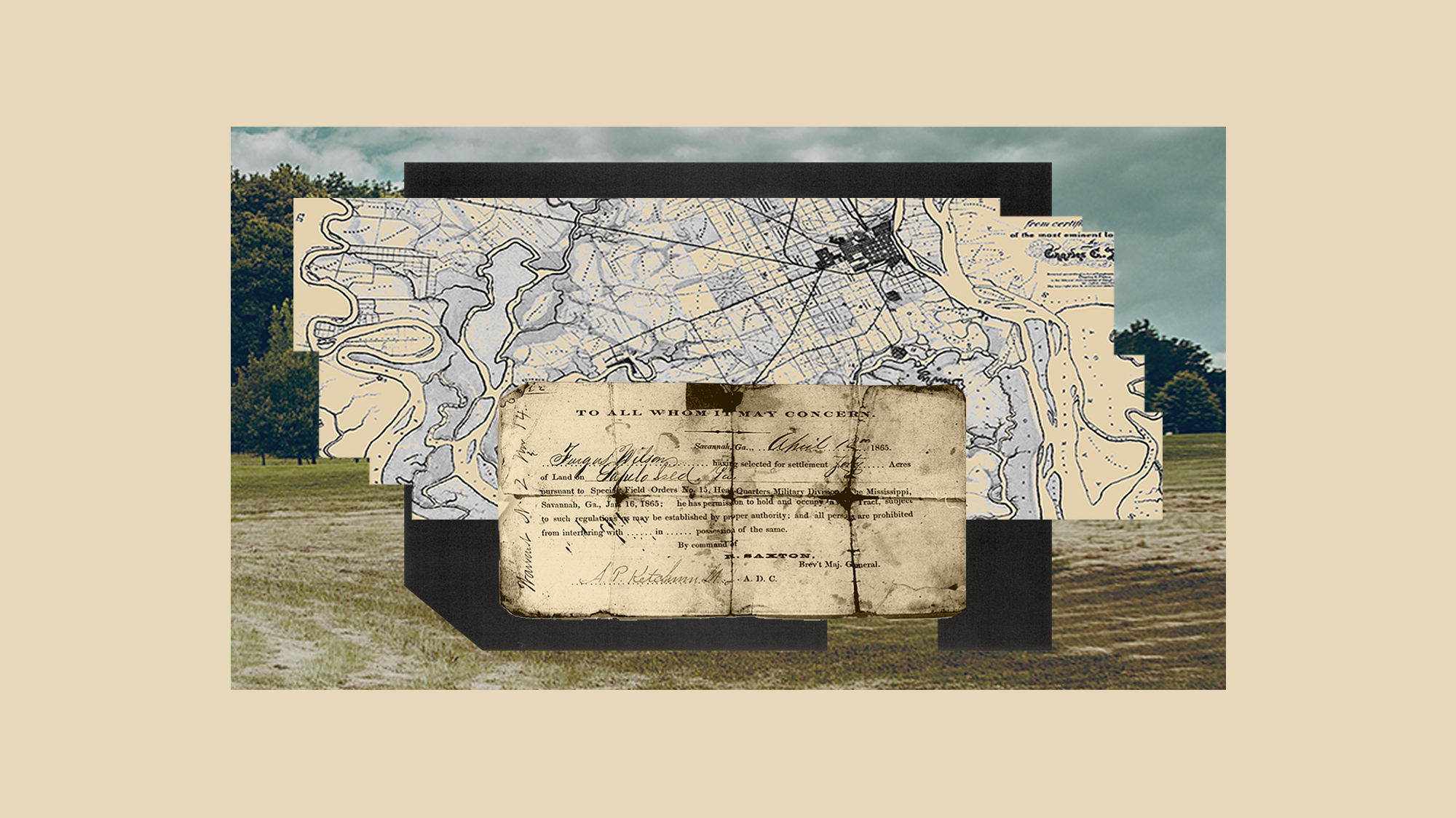

In 1865, Skidaway Island, Georgia, was becoming a Black utopia. Former cotton plantations gave way to a self-governing Black community. That is, until the federal government revoked 40 acres for tens of thousands of formerly enslaved people and returned the land to former slaveholders. Today, much of Skidaway Island belongs to The Landings, a wealthy, mostly white gated community.

40 Acres and a Lie, Part 3

40 Acres and a Mule has come to represent an unpaid debt, and it’s served as a rallying cry for generations of Black citizens demanding reparations. The final episode in this series explores how the debate around reparations has moved from the fringes to the mainstream, as a rising number of states, cities, and even one county in the South are actively exploring making amends.

Tools

Freedmen search

Click the button below to search Freedmen’s Bureau records by keyword, person, or location:

Freedmen who received land titles

The Center for Public Integrity identified 1,250 men and women who received land titles under Sherman’s Field Orders, No. 15. Below are their names along with additional information from reporters’ research. Search for information in any column or browse the table.

CREDITS

Contributors: Center for Public Integrity and the Investigative Reporting Workshop

Reporters: Alexia Fernández Campbell, April Simpson, Pratheek Rebala, Wesley Lowery

Story editors: Jennifer LaFleur, Wesley Lowery, Mc Nelly Torres, Jamie Smith Hopkins, Matt DeRienzo

Top editors: Clara Jeffery, Ian Gordon, Jamilah King

Audio producers: Nadia Hamdan, Roy Hurst

Audio editors: Cynthia Rodriguez, Brett Myers

Photographers: Adriana Iris Boatwright, Rosana Lucia, Janeen Jones

Digital tool developers: Pratheek Rebala, Jennifer LaFleur

Web developers: Robert Wise, Daniel Borges, Ben Breedlove

Illustrations: Chris Burnett

Additional illustrations: Michael Johnson

Senior designer: Michael Johnson

Creative director: Adam Vieyra

Photo director: Mark Murrmann

Copy editor: Daniel King

Researchers and fact-checkers: Peter Newbatt Smith, Jenna Welch, Ileana Garnand, Sophie Austin, Aallyah Wright, Audrey Hill, Elijah Pittman, Ruth Murai, Katie Herchenroeder, Sophie Hayssen, Sophie Hurwitz

Genealogy researchers: Vicki McGill, Sharon McKinnis

Document transcription: Terry Burks, Deborah Maddox, Selma Stewart

Partnerships: Lisa Yanick Litwiller, Ashley Clarke, Vanessa Freeman, Kate Howard

Audience engagement editor: Ashley Clarke

Legal counsel: Victoria Baranetsky