40 Acres and a Lie tells the history of an often-misunderstood government program that gave formerly enslaved people land titles after the Civil War. A year and a half later, almost all the land had been taken back. Read more here and listen to a three-part audio investigation here.

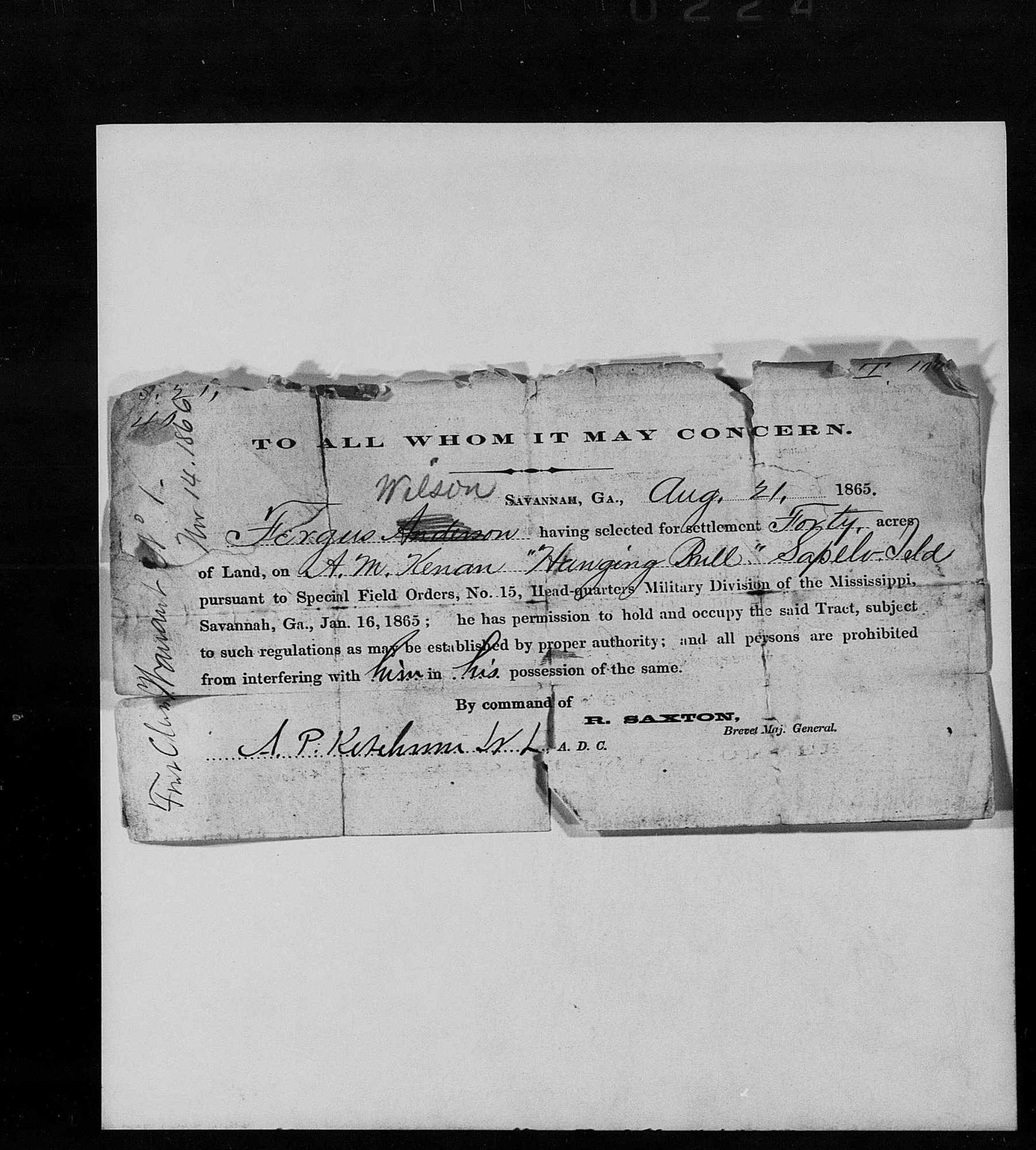

The black-and-white images of smudged, crumpled slips of paper caught my attention.

One was dated 1865 and named Fergus Wilson as the recipient of 40 acres on Sapelo Island, Georgia. I was looking at documents in the Smithsonian’s digital archives of the Freedmen’s Bureau, in a folder labeled “Unbound Miscellaneous Records.”

It was the fall of 2021, and I had only recently heard the phrase “40 Acres and a Mule” for the first time…in a song. Did I hear it from Nas in “You Owe Me” or Kanye in “All Falls Down”? Honestly I don’t remember. But I do remember googling the phrase immediately and was surprised to read about the government’s broken promise to Black Americans. I was surprised because it seemed like a significant moment in history but I don’t remember learning about it in school.

When reading Wilson’s name on the computer screen, I didn’t realize right away that I had come across a batch of land titles issued to formerly enslaved men and women as part of 40 Acres and a Mule, or that these historic documents were only recently digitized and made available online. In the same folder, I also found a log where Freedmen’s Bureau agents recorded the names of hundreds of people in Georgia who received the land titles, including Wilson. The images had been scanned from microfilm at the National Archives, where the Freedmen’s Bureau records are stored.

At the time, I was looking for land records related to a different investigative project. April Simpson, Pratheek Rebala, and I were part of a reporting team at the Center for Public Integrity that was researching gas pipelines in Black neighborhoods. I had talked to Andrea Roberts, then an assistant professor of urban planning at Texas A&M University, for advice on how to identify historic Black settlements across the country, something she had done in Texas. Roberts suggested I look for land records in the Freedmen’s Bureau collection.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know what the Freedmen’s Bureau was, but before long I was deep in the agency’s digital archives. The land titles I was looking at all said they were issued under the authority of Special Field Orders, No. 15. Soon enough, I realized I had found something important.

The very little I knew about the history of 40 Acres and a Mule from my Google search a year earlier gave me the impression that the promised land never materialized. That the formerly enslaved never got their 40 acres. Now I was looking at land titles and names, and I knew I had found a fascinating story. Maybe, just maybe, we could find the living descendants of Fergus Wilson and other named freedmen.

My colleagues were equally intrigued. I started searching academic texts and books to see what had been published about these land titles. Several historians mentioned their existence, and the context in which they were issued, but I couldn’t find images of the land titles published anywhere. Only one book I read named some of the people who got them, based on one of the Freedmen’s Bureau logs, Claiming Freedom: Race, Kinship, and Land in Nineteenth-Century Georgia by historian Karen Cook Bell.

As far as I could tell, no one had ever tried to track down their living descendants. I persuaded my team to ditch our other project and instead investigate the true story of 40 Acres and a Mule. Everyone was on board, but there was some skepticism that we could pull this off, especially the genealogical research.

Senior editor Jennifer LaFleur asked me to reach out to some experts to see if it was doable.

So I contacted the National Archives for help. I described the land titles I found and said I was struggling to find descendants of the people who received them.

“The furthest I can get is to their children, based on the 1870 Federal Census,” I wrote in an email to the press office.

The office put me in touch with archivist Damani Davis, the agency’s lead expert on the nearly 1.8 million records in the Freedmen’s Bureau collection. The day after we spoke, I updated the rest of the team.

“An archivist at the National Archives is doing some digging around for us,” I told them on Slack. “He thinks our project is ambitious, and will be hard, but not impossible.”

Next, I spoke with Hollis Gentry, who was then a staff genealogist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, for advice on how to do the genealogical research. Gentry was encouraging and enthusiastic about the idea.

“If you are frustrated with your research so far, that’s because what you’re trying to do is major,” Hollis wrote in an email after our conversation. She gave me advice on what records would help me track down their descendants. Hollis now oversees the Freedmen’s Bureau Transcription Project for the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, which has posted nearly 1.8 million records from the bureau online and is working with volunteers to transcribe them.

April, Pratheek, and I would spend two and a half years working to tell the true story of 40 Acres and a Mule with the help of many others on our team. We reviewed thousands of historical records, conducted hundreds of hours of genealogical research, interviewed dozens of sources, and employed artificial intelligence tools to find more land titles and names. We counted on the help of two American University students and two professional genealogists.

Reporting these stories would turn out to be much harder than we had imagined. Searching for living descendants meant countless nights looking at old census records and squinting at 19th-century handwriting until my vision blurred. Many of the freedmen who got land titles didn’t appear in any public records. In other cases, there were too many with the same name. And the freedmen and women we did find in the records often had their names misspelled or listed different birth years, a reminder that enslaved Americans didn’t have birth certificates.

Most records from the Reconstruction era are handwritten in ornate Spencerian cursive, which is nearly impossible for the average reader today to decipher at first glance. April, Pratheek, and I trained ourselves to read much of it, but the process was time-consuming.

All our work paid off. I was able to identify Fergus Wilson’s great-great-granddaughter and several living descendants of another freedman named Pompey Jackson. April identified multiple descendants of a freedman named Jim Hutchinson, who had gotten 40 acres on Edisto Island, South Carolina. Professional genealogist Vicki McGill helped us find others.

Meanwhile, Pratheek developed an image recognition algorithm to search for more land titles and logs in the bureau’s digital archives. We couldn’t search the nearly 1.8 million records by keyword, because training artificial intelligence to recognize all the different cursive handwriting was taking too long, and transcriptions were usually inaccurate. So Pratheek instead trained an AI model to look for images similar to the land titles I found, and the log of names. The model surfaced dozens more titles and hundreds more names in other logs.

In all, we identified more than 1,200 people who received possessory land titles for 4 to 40 acres of land in coastal Georgia and South Carolina as part of Special Field Orders, No. 15. Most of the names were extracted from the logs where bureau agents recorded each person who received a title and where. We also found about 150 images of the actual land titles and vouchers (the bureau gave vouchers to people who lost their titles, but who had been recorded in the logs as having received one).

The land titles and logs covered more than 26,000 acres on dozens of plantations that were seized by the Union Army from Confederate landowners. Though Special Field Orders, No. 15 covered parts of northeastern Florida, we didn’t find any land titles issued there.

Jennifer, Pratheek, former Public Integrity fellow Ileana Garnand, and I made dozens of trips to the National Archives Research Center in Washington, DC. We scanned thousands of pages of undigitized records, most of which were pension records for freedmen who served in the Union Army. Aside from the military records and Freedmen’s Bureau files, we relied on state historical archives, county property deeds, census records, plantation account books, county marriage licenses, and maps from the Library of Congress. The team overlaid historical maps onto modern-day maps to determine the approximate location of several plantations where freedmen and freedwomen received their plots of land. That helped me identify The Landings gated community in Georgia as the location of plantations where freed people got their 40 acres.

We ultimately created at least 100 family trees and identified 41 living descendants, several of whom April and I and Reveal’s Nadia Hamdan interviewed for this project. Some of them had no idea their ancestors had received land as part of 40 Acres and a Mule. We relied on public records and interviews with descendants to tell the stories of Pompey Jackson, Jim Hutchinson, and Fergus Wilson. Descriptions of conditions on the Grove Hill plantation in antebellum Georgia came from the research of historian Karen Cook Bell. Genealogists Vicki McGill and Sharon McKinnis checked our research to confirm that the people we interviewed are descendants of freedmen on our list.

We’re grateful to the Smithsonian for creating a digital archive of the Freedmen’s Bureau records, and to all their volunteers who are transcribing the documents. As of May, they had transcribed nearly 30 percent of the digital collection. Public Integrity commissioned other transcribers to translate military pension records, letters, and other documents.

As part of this project, Pratheek created an online tool to help the public search the transcribed documents by keyword and theme, and to search non-transcribed documents by image recognition. The collection includes marriage certificates, labor contracts, and letters, among other files. I encourage everyone to check it out. It surfaced many unpublished letters and documents that helped us bring this history to life. We’ve also published a list with the names of more than 1,200 freed people we identified and plantations where they received land.

We hope this investigation is just the beginning of a larger effort to tell the stories of people largely forgotten by history.

This project is a collaboration between the Center for Public Integrity, the Center for Investigative Reporting, and the Investigative Reporting Workshop. Read more here.

Top illustration: Michael Johnson: Source images: Freedmen’s Bureau Records; Library of Congress; Emiel Molenaar/Unsplash