Christl Mahfouz Moodie (left), owner of Ace Specialties store, and Lauren Hendrix arrange merchandise that will be offered for sale during the Republican National Convention.Mother Jones; Joe Raedle/Getty

Last month, Donald Trump reportedly called Milwaukee, host of this week’s Republican National Convention, a “horrible city.” He later tried to walk back the comments, saying, “I love Milwaukee,” but Trump’s initial comments revealed how the demonization of Milwaukee, a majority-minority city where 60 percent of Black voters in Wisconsin live, has been a central strategy of state and national Republicans.

Wisconsin Republicans—and Trump himself—owe their power in part to GOP efforts to suppress and dilute the city’s Black votes. It’s a strategy that dates back to when Governor Scott Walker and Republicans took control of the state after the 2010 election.

“We don’t want Wisconsin to become like Milwaukee,” Walker said in 2012, while courting white voters during a recall election. Wisconsin Republicans did everything they could to make sure that wouldn’t happen.

When Republicans passed a new voter ID law in 2011, requiring strict forms of government-issued photo ID to be able to vote, GOP members of the legislature said behind closed doors that it would target “neighborhoods around Milwaukee and the college campuses around the state,” according to the testimony of a former Republican legislative aide. Neighborhoods around Milwaukee was a widely understood euphemism for Black neighborhoods.

Some Republicans even said the quiet part out loud. On the night of Wisconsin’s 2016 primary, GOP State Sen. Glenn Grothman (now a member of Congress) predicted that a Republican would carry the state, even though Wisconsin had gone for Barack Obama by 7 points in 2012. “I think Hillary Clinton is about the weakest candidate the Democrats have ever put up,” he told a local TV news reporter, “and now we have photo ID, and I think photo ID is going to make a little bit of a difference as well.”

As I reported for Mother Jones, the law did indeed play a key yet little-noticed role in Trump’s surprise 23,000-vote victory in Wisconsin:

The state, which ranked second in the nation in voter participation in 2008 and 2012, saw its lowest turnout since 2000 [in 2016]. More than half the state’s decline in turnout occurred in Milwaukee, which Clinton carried by a 77-18 margin, but where almost 41,000 fewer people voted in 2016 than in 2012. Turnout fell only slightly in white middle-class areas of the city but plunged by twenty points or more in black ones.

After the election, registered voters in Milwaukee County and Madison’s Dane County were surveyed about why they didn’t cast a ballot. Eleven percent cited the voter ID law and said they didn’t have an acceptable ID; of those, more than half said the law was the “main reason” they didn’t vote. According to the study’s author, University of Wisconsin-Madison political scientist Kenneth Mayer, that finding implies that between 12,000 and 23,000 registered voters in Madison and Milwaukee—and as many as 45,000 statewide—were deterred from voting by the ID law. “We have hard evidence there were tens of thousands of people who were unable to vote because of the voter ID law,” he said.

The study also found striking socioeconomic and racial disparities among those most impacted. “The burdens of voter ID fell disproportionately on low-income and minority populations,” Mayer wrote. More than 20 percent of registrants coming from homes with incomes less than $25,000 said they were kept from voting by the law; 8.3 percent of white voters surveyed were deterred from voting, compared with 27.5 percent of African Americans.

Its impact was particularly acute in Milwaukee, where nearly two-thirds of the state’s African Americans live, 37 percent of them below the poverty line. Milwaukee is the most segregated city in the nation, divided between low-income black areas and middle-class white ones. It was known as the “Selma of the North” in the 1960s because of fierce clashes over desegregation. George Wallace once said that if he had to leave Alabama, “I’d want to live on the south side of Milwaukee.”

Neil Albrecht, Milwaukee’s election director, believes that the voter ID law and other changes passed by the Republican Legislature contributed significantly to lower turnout. “I would estimate that 25 to 35 percent of the 41,000 decrease in voters, or somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 voters, likely did not vote due to the photo ID requirement,” he said. “It is very probable that between the photo ID law and the changes to voter registration, enough people were prevented from voting to have changed the outcome of the presidential election in Wisconsin.”

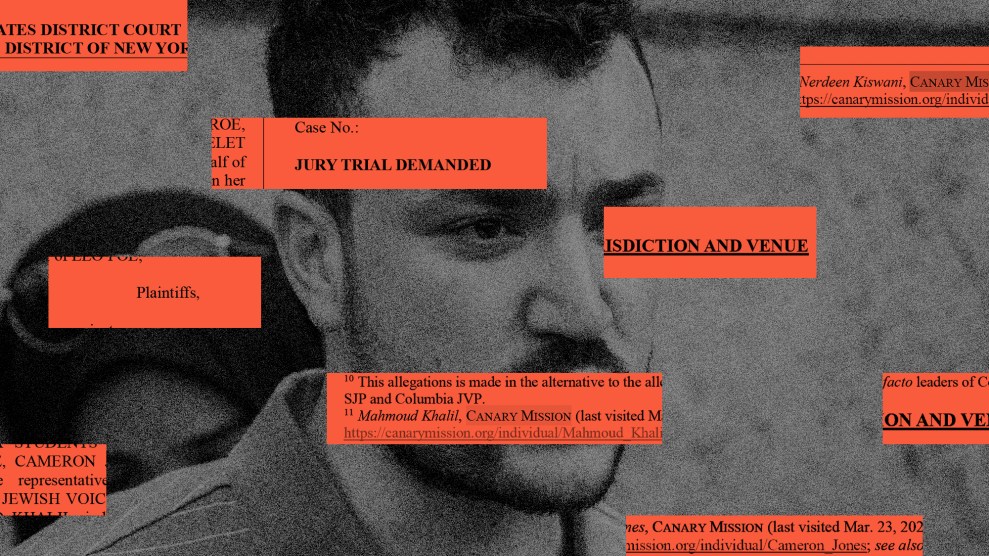

Four years later, Milwaukee became the epicenter of Trump’s push to overturn the election in the state. His campaign filed a lawsuit to disqualify 221,000 votes cast only in Milwaukee and Dane counties (encompassing Madison)—an unprecedented effort that was narrowly rejected by the state’s Supreme Court. After that failed, Wisconsin Republicans tried to decertify Biden’s victory by falsely claiming, among other things, that grants to help run elections during the pandemic in cities including Milwaukee amounted to “a wave of massive election bribery.”

Even though the campaign to throw out Milwaukee’s votes failed, Republicans successfully diluted the city’s voting power in another way—by gerrymandering Milwaukee and its increasingly Democratic-leaning suburbs. According to a lawsuit filed by voting rights groups, the legislative maps adopted by Wisconsin Republicans in 2021 preserved lopsided GOP majorities by weakening “the voting strength of Black voters in the Milwaukee area by packing them in excessively high numbers in fewer districts” while at the same time limiting Democratic representation in the city suburbs, which are trending blue, by spreading Democratic voters across oddly-shaped districts. (The legislative maps were struck down by the Wisconsin Supreme Court in December and fairer districts will be in place for November.)

Republicans have openly celebrated the decline in Black voting in Milwaukee. After the 2022 election, Robert Spindell, a Republican member of the Wisconsin Elections Commission and a fake elector for Trump, wrote that Republicans “can be especially proud of the City of Milwaukee (80.2% Dem Vote) casting 37,000 less votes than cast in the 2018 election with the major reduction happening in the overwhelming Black and Hispanic areas.” Spindell bragged to Republicans in the state’s Fourth Congressional District that “this great and important decrease in Democrat votes in the City” was due to a “well thought out multi-faceted plan.” Spindell is now a delegate for Trump at the GOP convention.

In addition to trying to undercut Milwaukee’s voter power, Republicans have sought to disregard the city altogether, arguing that it shouldn’t count at all toward state representation. After Republicans convened an unprecedented lame-duck session in 2018 to strip power from the state’s newly-elected Democratic governor, GOP Assembly Speaker Robin Vos said, “if you took Madison and Milwaukee out of the state election formula, we would have a clear majority.”

Republicans chose to hold the RNC in Milwaukee because they believed it would help them carry Wisconsin, but the GOP’s strategy to win the state is premised on undermining the power of the very city that is hosting them.

Local Black, Hispanic, and civil rights groups blasted the decision to hold the GOP convention in Milwaukee. “For at least two decades the Republican Party has been sticking it to Milwaukee,” they said in a statement. “Inviting the Republican Party to hold its convention in Milwaukee is like inviting the fox into the henhouse.”