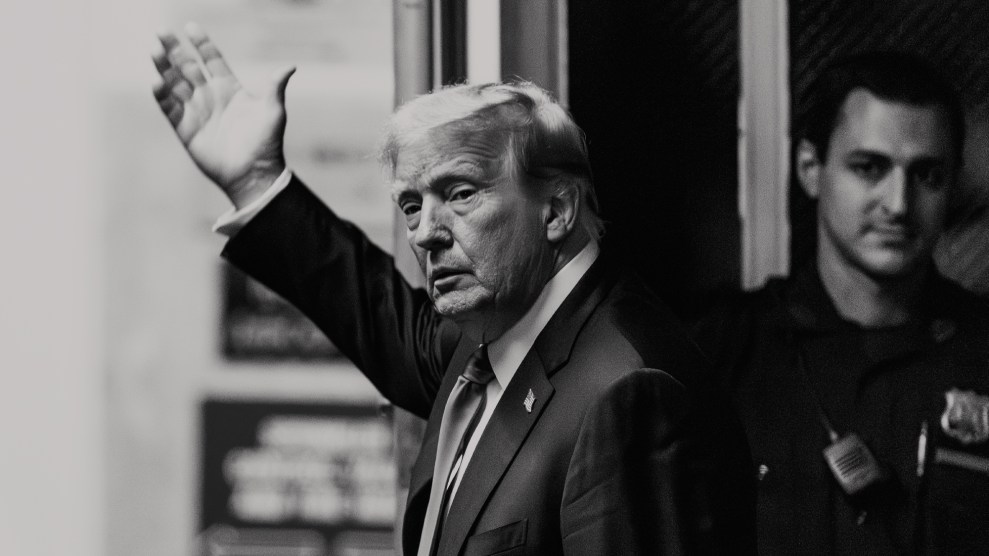

Justin Lane/Pool/Getty

The Supreme Court on Monday ruled that presidents have broad criminal immunity for official acts, effectively placing the presidency beyond the reach of criminal law for the first time in the country’s history. The 6-3 decision along ideological lines sends the federal case over Donald Trump’s attempts to overturn the 2020 election back to the district court to determine whether Trump’s actions fall outside the court’s sweeping new grant of immunity—but the effects will stretch far beyond Trump’s possible trial by fundamentally changing the nature of the presidency and, by extension, American democracy.

In an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts, the Republican-appointed justices held that presidents have immunity for official acts. The opinion left to another day whether that immunity is absolute, or whether it can be pierced in some circumstances. Despite the possibility for exceptions, the decision is sweeping and radical.

“The ruling is a bigger win for Trump than many of us had been expecting.”

“Today’s decision to grant former Presidents criminal immunity reshapes the institution of the Presidency,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissent, which was joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson. “It makes a mockery of the principle, foundational to our Constitution and system of Government, that no man is above the law.”

The case arose out of Special Counsel Jack Smith’s criminal charges against Trump for trying to subvert the election. As a defense, Trump argued that he is immune from prosecution for official acts made while in the White House—a sweeping theory without a basis in the Constitution. The framers, who were adamant that the presidency not resemble the monarchy they had just fought a revolutionary war to escape, purposefully left presidential immunity out of the Constitution. They were explicit that presidents would not be above the law, an assumption that had continued until today: Indeed, President Gerald Ford famously pardoned former President Richard Nixon—a result of the understanding that without doing so, Nixon might face criminal charges.

Before the case reached the Supreme Court, the district court and court of appeals had both rebuffed Trump’s claims. But at oral argument before the high court, several Republican-appointed justices were preoccupied with the idea that ex-presidents would be under siege from prosecutors waging backward-looking, politically motivated cases unless the court granted presidents new levels of immunity. Monday’s decision relies on a related idea that presidents need immunity in order to effectively govern: the framers, the majority argued, envisioned a vigorous executive and immunity would ensure the office’s strength.

“Immunity is required to safeguard the independence and effective functioning of the Executive Branch, and to enable the President to carry out his constitutional duties without undue caution,” Roberts wrote.

In her dissent, Sotomayor argued that majority goes so far as to create not a robust executive but, essentially, a monarch. “In every use of official power, the President is now a king above the law,” she wrote. In a separate dissent, Jackson warned that the gift of immunity would not engender benevolence: “The seeds of absolute power for Presidents have been planted,” she wrote. “And, without a doubt, absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

The decision will not only significantly delay the special counsel’s trial against Trump for election subversion but likely result in most charges being dropped. Because the decision leaves the door open for prosecution for unofficial acts, the question is whether any of Smith’s charges relate to unprotected conduct. In a concurrence, Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote that she believed at least one charge relating to the scheme to create fake slates of electors should proceed to trial. As to other charges, Roberts ruled that immunity applies “unless the Government can show that applying a criminal prohibition to that act would pose no ‘dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.'” That is a high bar—and it’s unclear what criminal prosecution, if any, might clear it.

“Just so everyone understands the radical import of the decision: The Court holds that even when the POTUS clearly—or even *concededly*—abuses his or her office to violate a valid federal law, that POTUS cannot be tried, even after leaving office,” constitutional law expert Marty Lederman wrote online.

The opinion further insulates the president by finding that a president’s official and protected conduct, even when criminal, cannot be introduced as evidence at a trial taking place for prosecutable conduct. The result is that even where this sweeping immunity does not touch, a finding of guilt will be made more difficult. (Barrett did not join this part of the majority’s opinion, writing that “The Constitution does not require blinding juries to the circumstances surrounding conduct for which Presidents can be held liable.”)

“This is a big part of why the ruling is a bigger win for Trump than many of us had been expecting,” Georgetown Law professor Steve Vladeck explained. “It’s not just which acts will be immune; it’s how this will hamstring efforts to prosecute even those acts for which there *isn’t* immunity.”

The justices could have decided this matter quickly and narrowly, or declined to take it up all together, and allowed a trial to proceed. Instead, at every stage of the case, the justices indulged Trump’s attempts to slow-walk proceedings. His immunity defense was always as much about pushing the trial date after the election—which would help him win the election and eliminate the case entirely—as it was about mounting a sound legal defense. But the biggest gift to Trump was to give him a nearly complete victory.

The GOP-appointed justices have now helped Trump in two ways. First, he will escape trial for the foreseeable future, as lower courts wrestle with applying Monday’s decision. Second, they have granted the presidency new powers that Trump can take advantage of if he returns to power.

Trump has already made his intentions clear: He will weaponize the Justice Department to prosecute his political enemies. “I will appoint a real special prosecutor to go after the most corrupt president in the history of the United States of America, Joe Biden, and the entire Biden crime family,” Trump promised last year. Ironically, Trump is promising to bring about the very destruction of DOJ independence that several justices claimed they were worried about during oral argument.

Instead of protecting the president from bogus prosecution, they created more incentives for the president himself to launch such prosecutions—and to ignore virtually every other law as well.

“When he uses his official powers in any way, under the majority’s reasoning, he now will be insulated from criminal prosecution. Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organizes a military coup to hold onto power? Immune. Takes a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune. Immune, immune, immune,” Sotomayor warned. “With fear for our democracy, I dissent.”