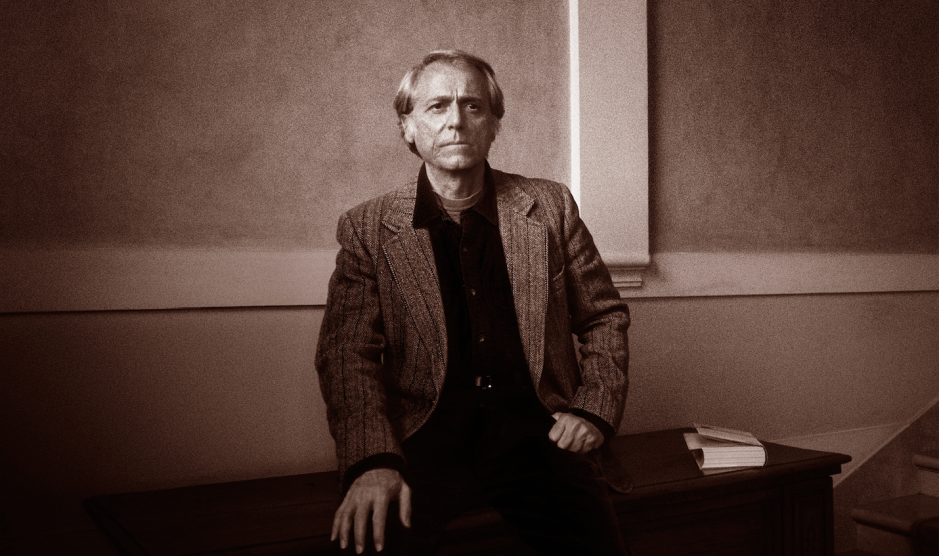

Leonardo Cendamo/Getty

One summer after college, I decided to learn how to write—and, more importantly, to read.

I was around 21. I had read almost no books in my life. And, so, I spent a summer basically alone—applying for jobs, doing some data entry for money—and following the routine I’d read that Don DeLillo kind of half-way does.

“I work in the morning at a manual typewriter. I do about four hours and then go running,” he said in a Paris Review interview. “This helps me shake off one world and enter another. Trees, birds, drizzle—it’s a nice kind of interlude. Then I work again, later afternoon, for two or three hours.”

I tried that. All of that writing time was too much for me. I’d have nothing to say if I wrote for seven hours a day. But, still, I woke up early, wrote for as long as I could, ran, and then read. Usually, by 10 in the morning, I was bored.

Still, it was approachable. For how high-flung DeLillo can seem, it has always been easy to walk up to his view of life: He likes baseball, he likes reading, he likes running, he feels like we’re all trapped in a paranoid nightmare, and he has a compulsion to trace it back to the Kennedy assassination.

His newest book hits the same tone, from the sound of it in the review. He has a nice interview in the New York Times too, which I found charming and human—still glinting with that metallic, cold DeLillo edge.

Sometimes—or should I say in that horrific phrase that indicates these plague years, “in this time”—it can help to return to the things that we know we enjoy.

Whether reading DeLillo has helped me write is up for debate (please inquire with my editors, who have seen my gangly sentences and personal dictums about how grammar functions, including a first pass of this sentence, which started, “How reading DeLillo has turned out to learn how to write…”). But he certainly taught me, in his writing, not to fear the simplicity of American life, and not to fear aspiring to make it higher art. Just look at his writings on baseball. Or that opening sentence, added to his novella Pafko at the Wall when it became the introduction to Underworld: “He speaks in your voice, American, and there’s a shine in his eye that’s halfway hopeful.”