Paul Butterfield/Getty/Amazing Comic Conventions

One of the first comics I remember reading was Crisis on Infinite Earths, an altogether ridiculous DC Comics series from the mid-’80s that featured approximately 1 billion characters fighting a villain named the Anti-Monitor. I don’t know why or how I stumbled upon a collected edition of those 12 comics, which require a PhD in dense comics lore to understand, but I absolutely loved them.

And the reason why was George Pérez.

The Anti-Monitor’s days are numbered.

George Pérez/DC Comics

For young fans like me, superhero comics felt like a secret passcode only you and your friends knew. Sure, the world might think this is silly, but to us, it’s the coolest thing going. How can you explain to someone what works about a bunch of weirdos in spandex fighting aliens or robots? It just does.

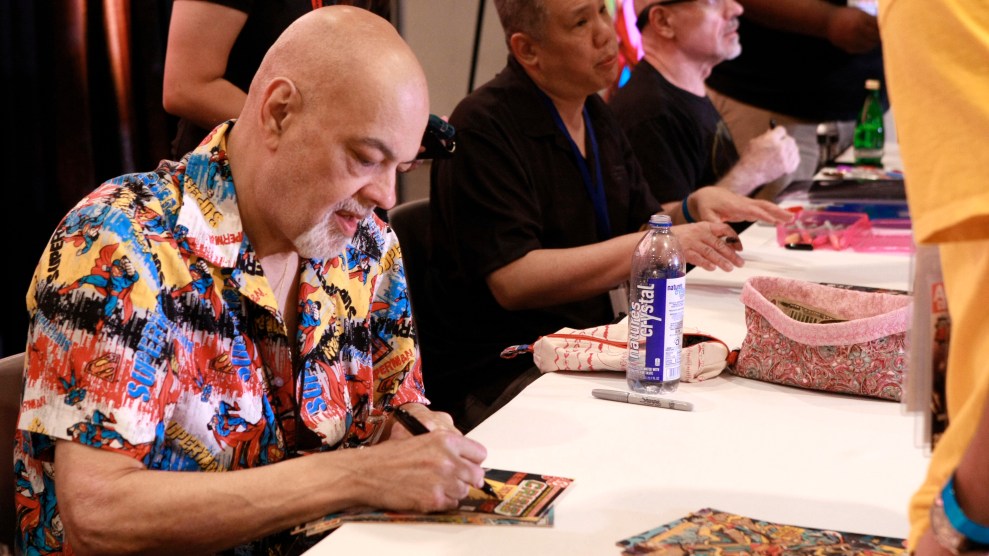

Pérez, an iconic artist and writer who died Friday, at 67, following a battle with pancreatic cancer, was as important as anyone else in giving comics that sense of wonder and dynamism.

His prolific career extended across decades at both major comics publishers, DC and Marvel, but his ’80s work is what I remember best. The ’80s was an incredible decade for superhero comics. The year Crisis wrapped up, DC started publishing two massively influential series: Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen, arguably the most critically acclaimed comic of all time. Those comics, like much good art, revolutionized the form by making its competition look dated, overly simplistic, and morally suspect. Superheroes are not to be idealized or worshipped, Watchmen tells us. They are just as greedy and vain and violent as the rest of us. If anything, their power makes them act worse.

But in Crisis and his long-running stint on The New Teen Titans, Pérez had an old-school appreciation for the joy of serialized superhero comics. His colorful characters burst off the page and sometimes barely fit on it—literally. His ability to draw crowd scenes, something other comics artists loathe, was legendary. In a time when superheroes have taken over popular culture, Pérez reminds us why they appealed to readers in the first place.

Superhero comics are not just for children—sorry, Alan Moore—but at their best, they do evoke a sort of childlike wonder that is hard to explain. (Though when your boyfriend is 20 minutes into explaining the Doctor Strange post-credits scene, you may know what I mean.) I can’t remember much about Crisis or the individual issues of Teen Titans, but I know how important the characters felt to me. I was invested in Robin and Beast Boy and Raven as if they were longtime friends.

Part of the beauty of comics—despite being an industry rife with some not-so-beautiful things—is how easy it is for fans to come to know, or at least feel like they know, popular creators. When Pérez announced in December that his cancer was inoperable and that he had denied further treatment, I was struck by the unbelievable generosity he showed his fans. “I hope to coordinate one last mass book signing to help make my passing a bit easier,” he wrote on Facebook. “I also hope that I will be able to make one last public appearance wherein I can be photographed with as many of my fans as possible, with the proviso that I get to hug each and every one of them. I just want to be able to say goodbye with smiles as well as tears.”

The following months brought more Facebook updates as Pérez visited with fans and fellow comics creators like Kurt Busiek, with whom he published an amazing DC/Marvel crossover series featuring the Avengers and the Justice League. That series, like Pérez at his best, evoked the thrill of seeing your childhood dreams made manifest.

I’ll never feel about today’s comics now the way I did as a kid. The ever-expanding superhero-industrial complex has robbed some of that context-free glee from the material, but every time I look at one of Pérez’s pages, I remember what made me sit next to a bookshelf in my parents’ basement, racing to see how the Anti-Monitor would be defeated.

I don’t remember how the heroes won. I just remember how it made me feel.