Julian Assange already hates this movie. That six-word review may be all that his die-hard supporters need to know about We Steal Secrets, Alex Gibney’s exhaustive and exhausting new documentary on the rise and fall of WikiLeaks. Apparently without having seeing the film, which hits theaters tomorrow and will be available on demand on June 7, Assange has condemned it as a hatchet job, starting with its name. “An unethical and biased title in the context of pending criminal trials,” WikiLeaks tweeted in January when the movie screened at Sundance. “It is the prosecution’s claim and it is false.”

Assange’s preemptive attack reinforces one of the film’s main themes: What happens when an admirable cause is headed by a thin-skinned, combative prick?

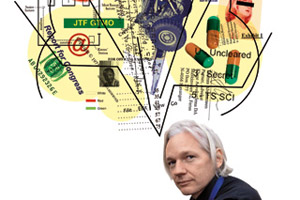

Like many observers of WikiLeaks’ short, chaotic history, Gibney (Taxi to the Dark Side, Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer) starts out sympathetic before souring on Assange. At first, We Steal Secrets seems enthralled with its subject. When Assange quotes a favorite Midnight Oil song, Gibney obligingly blasts the tune—a haranguing one even by the band’s standards—over a title sequence that ricochets through cyberspace.

What follows is a complimentary look at Australia’s “most infamous hacker,” a peripatetic cryptographic whiz who recognized the promise and threat posed by a site that could publish anonymous leaks from around the globe. Robert Manne, a professor of politics at La Trobe University in Melbourne, gushes that Assange is “a humanitarian anarchist, a kind of John Lennon-like revolutionary, dreaming of better world.” Or as Assange declares with casual bravado, “I enjoy crushing bastards.”

Gibney gives Assange and WikiLeaks plenty of credit for their greatest hits, which culminated in the massive leaks of 2010, namely the “Collateral Murder” video, the Cablegate documents, and the Afghan and Iraq War Logs. “Collateral Murder,” shown in the film, still packs a sickening punch: An American helicopter crew in Baghdad mows down a group of men identified as militants—two, in fact, were Reuters journalists—and then strafes a van that arrives to help the wounded. When the helicopter crew learns that the vehicle was carrying two children, one responds, “It’s their fault for bringing their kids to a battle.”

Among their many revelations, the Iraq War Logs detailed how the US military had handed over detainees to Iraqi forces knowing that they could be abused, tortured, or summarily executed—a violation of international law. Gibney, who narrates the film, concludes that “the Obama administration appears to have committed war crimes.”

But in its second hour, We Steal Secrets sinks a knife into its subject as a series of disillusioned allies steps up to testify against him. Former WikiLeaks staffer James Ball diagnoses Assange with a case of “noble cause corruption”—unable to recognize when he does things that he would deplore in others. Manne qualifies his earlier praise, asserting that Assange is “a natural fabulist and storyteller and lives intensely in his imagination.” Nick Davies, a Guardian reporter who worked closely with Assange, recalls his callous attitude toward sources named in American military documents whose lives might be jeopardized if their identities were not redacted: “I raised this with Julian and he said, ‘If an Afghan civilian helps coalition forces, he deserves to die.’ He went on to say that they have the status of a collaborator or an informant.”

Gibney also interviews Anna, one of two Swedish women who have accused Assange of sexual assault, setting off the chain of events that has led to his self-imposed exile inside the Ecuadorian Embassy in London for the past 11 months. Since speaking out against Assange at the height of his celebrity, she’s been the target of vicious trolling. “I’ve been through two years of different kinds of abuses,” she recounts. “People coming to my house, people threatening, or questioning, or following my friends and family. Some death threats, but mostly sexual threats that I deserve to get raped.” She believes Assange bears some responsibility for not reining in his devotees. “They admire him very much and he could have easily stopped that.”

Gibney dismisses Assange’s claim that the Swedish investigation is a ruse to get him extradited to the United States to face trial for espionage. (A federal grand jury has considered charges against Assange; no indictments have been filed yet.) However, the film overplays its hand when it mentions that Assange reportedly has had four children with four different women “around the world,” suggesting that he’s not only into crushing bastards but fathering them.

Although We Steal Secrets includes plenty of footage of Assange from various sources, he was not interviewed for the film. Gibney says he met off-camera with Assange for six hours, only to be told that “the market rate for an interview with him was $1 million dollars.” Gibney balked at this, as well as at Assange’s offer to talk if the filmmaker would tell him what his other interview subjects were saying about him. (Update: WikiLeaks denies this and has responded to Gibney’s “errors and sleight of hand” with an annotated transcript of the film. Gibney says the WikiLeaks’ transcript is incomplete.)

Although Assange’s story dominates We Steal Secrets, it’s just one of three parallel storylines. Another is the rise of national security state and the massive expansion of official secrecy following September 11. Gibney assembles an impressive cast of insiders to provide context on the obsessive and often unnecessary secrecy that WikiLeaks was set up to combat. Yet these interviews feel like excerpts from an unfinished companion film (which Gibney should make). “We produce more secrets than we’ve ever produced in the history of mankind,” says Bill Leonard, the Bush administration’s classification czar. “And yet we never fundamentally reassessed our ability to control secrets.” Former National Security Agency and CIA chief Michael Hayden, the source of the film’s contentious title, admits that the federal government does exactly what it pursues whistleblowers (and now, reporters) for doing: “Let me be very candid, all right. We steal secrets.”

Enter Bradley Manning, the film’s shadow protagonist. Manning is the Army private who’s been imprisoned for more than 1,000 days while awaiting a military trial for giving WikiLeaks the helicopter video, state department cables, and war logs. Like Assange, he comes off as an idealistic misfit who found purpose in his digital mastery and his access to official secrets. But Manning remains an enigma. Much of his story is fragmentary, told through the messages he exchanged with Adrian Lamo, the hacker who drew him out in a series of private chats and then turned him in. Was Manning’s alleged crime a considered statement of conscience or the indiscriminate act of an unhappy GI—or both? We Steal Secrets can’t really say. (A detailed statement Manning read at a court martial hearing in February offers more insight into his motivations.)

We Steal Secrets may provide a new focal point for WikiLeaks’ supporters and detractors. But it also reminds us just how much the group has been sidelined. The wiki part of WikiLeaks is history: The site’s dropbox for leaks has been shuttered for more than two years. And the leaks have gone cold: Its biggest recent coups have been security-firm emails lifted by Anonymous and the re-release of 40-year-old documents that confirm the horribleness of Henry Kissinger.

Assange’s current state of limbo is captured near the end of We Steal Secrets. Over Lady Gaga’s irresistible “Telephone,” one of the songs Manning listened to as he allegedly orchestrated his massive document dump, Gibney plays a clip of Assange dancing, unselfconsciously and unapologetically, by himself.

This story has been updated.