James Colburn/Zuma

At a gun show in San Francisco’s Cow Palace, between a table of switchblades and a rack of Enfield rifles, David McBride sat glumly under a “Ron Paul for President” banner. The shy, 28-year-old software tester had driven in from Silicon Valley and wasn’t sure how to chat up nra members chewing elk jerky—or, for that matter, the dozen-or-so Paul supporters he’d come to know via Meetup.com but had never met in the flesh. So he pulled out his iPhone and began searching for the latest Paul headlines. Instantly, the geeks gathered: Was the phone’s camera 2.0 megapixels? Was Paul gaining in the Iowa Republican straw poll? “I’m waiting until they come out with the one that has ActiveSync,” a ponytailed computer consultant said. The group nodded knowingly.

Their candidate, a 72-year-old obstetrician from Lake Jackson, Texas—land of duck hunters, ranchers, and oilmen—has improbably become an Internet sensation. He counts more Facebook and MySpace supporters than any Republican; more Google searches, YouTube subscribers, and website hits than any presidential candidate; and more Meetup members than the front-runners of both parties combined. In recent months he was sought out on the blog search engine Technorati more often than anyone except a Puerto Rican singer with a sex tape on the loose; his November 5 Internet “Money Bomb” event pulled in $4 million from more than 35,000 individual donors, a single-day online-fundraising record in a primary. (The previous best was $3 million, by John Kerry.) “The campaign calls itself the Ron Paul Revolution,” notes Republican Internet consultant David All. “And I don’t think that’s a far stretch.”

Indeed, Paul’s literature is dominated by the word “revolution,” though with the middle letters inverted to make “love”—a hippie touch that would be countenanced by few Republicans other than the congressman, who has been elected 10 times on the GOP ticket (and who also ran as a Libertarian in the 1988 presidential election). The truth is, Paul’s revolution is a conservative one, by his own account—and thus all the more noteworthy for Democrats, who until now comfortably assumed that progressive bloggers, YouTubers, and ex-Deaniacs would give them, and only them, an edge online. As it turns out, nobody has more Internet buzz than a pro-gun, pro-life, antitax, and antiwar Republican.

In the Cow Palace, the buzz came mostly from a table of 100,000-volt stun guns; McBride’s table was just a sideshow. “I don’t know anything about him,” said the guy selling Jungle Survivor knives a few tables down the aisle. The national media has mostly ignored Paul, who garners no more than 6 percent of the gop electorate in phone surveys, and Democrats liken his surprising victories on Internet straw polls to the Sanjaya effect: The web loves weirdos.

But maybe the offline world just hasn’t seen the right YouTube clips. McBride had downloaded them onto dvds, intending to bring the Net into meatspace. He steeled himself, pocketed the iPhone, and corralled Brian Timpanaro, who was walking by in a bulging stp Oil shirt. “Here’s some of Ron Paul’s stances,” he said, quickly ticking off Paul’s position against drug prosecutions, gun control, and the Iraq War. Timpanaro shot back with a cranky denunciation of peace protesters, but walked off clutching a dvd. McBride stacked the remaining discs on his table and called it a day. “I’m one of the more introverted activists you will find,” he explained.

And yet McBride is also part of a surprisingly powerful political phenomenon—a shock troop of volunteers who’ve been working long hours, often within the autonomous confines of their living rooms, to make Paul’s online machine the envy of Washington. “You might not know it, but when I’m not eating, sleeping, at work, or taking care of my daughter,” McBride told me, “I’m working to get Ron Paul elected.”

Paul, a popular doctor who maintained the only ob-gyn practice in his county, was first elected to Congress in 1976. He voted with clinical precision against almost every government-spending bill to cross his desk, even when it meant that his constituents lost out on farm subsidies or money for hurricane protection, earning him the nickname “Dr. No.” Politically, his forebears are Senator Robert Taft and Rep. Howard Buffett—the Old Right, pre-National Review. “They understood that war was a big-government program,” says Paul’s former chief of staff, Lew Rockwell, whose website is one of the most popular libertarian destinations on the Net.

By and large, Paul’s acolytes are not the kinds of people you’ll find in a Republican campaign—or any campaign. Having, in many cases, never even voted, they are driven by an unalloyed certitude that Americans will be won over to Paul by the sheer force of his antigovernment ideas (and judicious use of social-networking tools). You could call them techno-publicans. And while their success doesn’t readily translate to the offline world, their passion and organization have made them a force to reckon with. Once Paul is knocked out of the gop contest, will they dissipate, gravitate toward someone else, or reemerge with a third-party bid? (Libertarians have been spoilers for the gop before; in Montana’s close 2006 Senate race, a Libertarian drew more votes than the entire Democratic margin of victory.) Whichever way the Paulites go, other candidates would be smart to study their movement’s trajectory. It, not Paul, is the real revolution.

Growing up in Pinetop, a conservative town of 3,000 in the White Mountains of Arizona, McBride learned to cherish freedom and blast clay pigeons with the family’s 10-gun arsenal. Then, for three glorious months in 1992, he found a Marvel Comics chat room and legions of fellow X-Men fans. When his parents looked at the phone bill—and realized that connecting to aol meant a long-distance call—14-year-old David went back to target practice.

In 1994, McBride’s father, a physician, was disabled in a car accident. His mother died a year later of a prescription mix-up. The family fell into debt. “That’s when I came to the realization that life isn’t fair,” says McBride, whose shaved head, goatee, and coiled physique contrast with a soft voice and gentle demeanor. At 16 he took a job bagging groceries; unlike his older siblings, he’d have to pay for community college himself.

In 1999 McBride dropped out of school and drifted from a job as a used-car-lot manager in Tucson to a seasonal gig supporting the Intuit software MacInTax. Three years later Intuit brought him to Silicon Valley as an application tester. Now there were no limits to his surfing; for hours each night he sat glued to his iMac, sating a growing Apple obsession on sites such as daringfireball.net. “Everything on a Mac makes sense,” he says, “when you are coming from a Windows world.”

Outside his operating system, the world seemed ever more inscrutable. He read on Google News about the Patriot Act, Guantanamo, and the profiling of Muslim Americans. Through his brother in Tucson, he discovered LewRockwell.com, which convinced him that the U.S. government had brought on 9/11 with its policies in the Middle East. McBride had never gotten much help from the government; now he felt downright threatened by it. He was, in other words, becoming part of the 15 or so percent of Americans who consider themselves libertarians. This group has historically voted Republican—enthusiastically for Goldwater in 1964 and Reagan in 1980—but by 2004 many of them broke from the gop. McBride was outraged by the invasion of Iraq, registered to vote for the first time in his life, and cast a ballot for Senator John Kerry, even though he disagreed with his economic policies. “I just thought he would be less dangerous than Bush,” he said. “Thousands of people were dying for no good reason.”

The next year, after Hurricane Katrina struck, McBride seized on the pressing question on LewRockwell.com: Why had fema blocked Wal-Mart from bringing in supplies? “They understand the environment better, the people better; they know what’s needed,” he thought. It became clear to McBride that private entities such as the Gates Foundation were more likely to end poverty than the government, that Toyota was best equipped to stop global warming, and that Intuit knew more about taxes than the feds did.

By 2006, McBride was so disgusted with the federal government that he sat out the election, and the new Congress’ failure to extricate America from Iraq wiped out his last bit of allegiance to the system. He told himself he’d never vote again. Why bother? Nobody who was against big government, the war, and the Patriot Act could ever win.

During the second Republican primary debate, held on the campus of the University of South Carolina in mid-May, Ron Paul stood at a lectern at the far end of the stage. He’d seldom be allowed to speak that evening, but a rare chance came when Fox’s Wendell Goler asked why he wanted the gop nomination given that he opposed the war. Paul said terrorists had attacked the United States because of its entanglements in the Middle East. Murmurs filled the hall. “Are you suggesting we invited the 9/11 attack, sir?” Goler inquired.

“I’m suggesting that we listen to the people who attacked us and the reasons they did it,” Paul replied. When the bell cut him off a few seconds later, Rudy Giuliani jumped in. “That’s an extraordinary statement,” he seethed. “I don’t think I’ve ever heard that before, and I’ve heard some pretty absurd explanations for September 11.” Egged on by the audience’s cheers, Giuliani demanded that Paul withdraw the comment. Goler swiveled in his chair. “Congressman?”

What Paul said next would stream from YouTube more than half a million times, and inspire McBride like no other moment in his young political existence. “I believe very sincerely that the cia is correct when they teach and talk about blowback,” Paul said. “[Terrorists] don’t come here to attack us because we’re rich and we’re free. They come and they attack us because we’re over there. I mean, what would we think if other foreign countries were doing that to us?”

Straw polls on abc and msnbc showed Paul as the debate’s resounding winner, and even on Fox’s own text-message poll, he nearly tied Mitt Romney for first. For McBride, “It was enough to get me to jump on the bandwagon and say, ‘Maybe this guy does have a shot.'” In the following months, the San Francisco Ron Paul Meetup group grew more than thirtyfold; nationwide, more than 60,000 people have signed up for Paul Meetups. Many listed Paul’s stance on Iraq as a top reason for their support. While antiwar Democrats such as Dennis Kucinich want to pull out the troops as they are replaced by international peacekeepers, Paul would have them “just come home” no matter what—and, immediately thereafter, kill off the entire military industrial complex along with the “medical industrial complex” and the “educational industrial complex” and the personal income tax. “We can’t cut anything until we change our philosophy about what government should do,” Paul said in the debate. On that night, he politicized a new generation of libertarians.

Paul fever soon spread to the popular, tech-oriented news aggregator Digg, where McBride and other enthusiasts began to search, post, and comment on everything Paul, to the point where the candidate now consistently dominates the top 10 election stories on Digg’s front page. Paul continues to win major Internet polls with the help of emails and chat-site notes exhorting his troops to vote. His victories have often been such routs—87 percent of the vote in the abc post-debate poll, for example—that some media outlets have spiked the polls or removed his name, and bloggers have wondered if his supporters were unleashing malicious web bots. The true answer is probably far simpler: At the core of the Ron Paul juggernaut are thousands of obsessive techies for whom online organizing is not a special effort, but second nature.

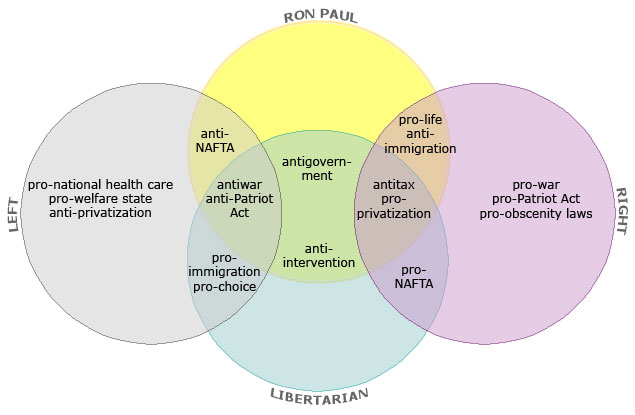

The Venn of Paul: As befits a movement with mainstream aspirations, libertarians have taken a big-tent approach to ideological purity. A pro-life, anti-immigration conservative like Ron Paul is welcome, as is a free-love prophet like the late Robert A. Heinlein—and, of course, libertarian thought overlaps with segments of both left and right.

—J.H.

In July, Paul flew to Silicon Valley to speak at the Mountain View headquarters of Google. He spun through the Googleplex, past the life-size Tyrannosaurus rex and the corporate organic garden and into an auditorium overflowing with workers balancing laptops on their knees. Hillary Clinton, John Edwards, and John McCain had appeared here, but none had drawn a comparable crowd, nor as many questions—or manifestos—emailed in advance from Google staffers. “When John McCain and Hillary Clinton were standing up ready to stamp their approval on the Patriot Act, you’re one of the people in Congress who said, ‘No, absolutely not,'” a worker who’d flown from Seattle told Paul during the Q&A. “And that really impressed me.” There was a webcast, and a rockumentary; Bill Dumas, Paul’s official videographer and a member of the band Blonde Furniture, provided the soundtrack’s chant, “If you Google Ron Paul…,” an homage to the idea that all you need to know about Paul is on the Internet. A few weeks later YouTubers produced a Ron Paul rap (“Yeah we know our Homeland Security and FEMA / Just look at how they protected us from Hurricane Katrina”), and then a Ron Paul folk ballad, a synth-pop track, and a riff on the Scarecrow’s “If I only had a brain.”

By then, roughly 10 percent of Paul’s donations over $200 were coming from tech workers. No business sector has raised more for Paul; in Google’s hometown, Paul logs more contributions than all the Republican front-runners combined. He has garnered links to his donation page from a broad array of websites—troublingly broad, in fact: In November, he refused to return a contribution from avowed white supremacist Don Black, or to block the donation link from Black’s website. McBride’s favorite, dailypaul.com, has more daily viewers than the official John Edwards website (albeit according to the notoriously skewed Alexa ratings).

This is all the more remarkable because, though tech wealth has historically supported libertarian causes, the industry’s money in recent years has shifted to buying political firepower in the major parties. For example, since the 1990s, McBride’s libertarian-inclined boss, Intuit founder Scott Cook, has more than doubled his donations to Republicans and Democrats, giving the maximum last year to mainstream politicians such as Mitt Romney and Harry Reid.

Still, the romance of libertarianism endures for Silicon Valley’s rank and file. Scott Loughmiller, a partner in a six-man dot-com startup in San Carlos, says he has converted all his coworkers to the Paul credo. “You can argue all you want, and they did for a month,” he said, “but eventually they caved, because you have to give in to logic.” Paul’s name shows up hand-stamped on dollar bills, emblazoned on freeway banners, and on roads across the valley via a big white delivery truck known as the Liberty Van. In August McBride changed his voter registration from “Decline to State” to “Republican” so he could vote for Paul in the primary.

In the techie brain, self-interested antigovernment leanings—many Valley libertarians are furious about the investor-protection rules of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, a law they blame for driving Wall Street IPOs to London—cross-pollinate with the yearning for a reassuringly Cartesian political philosophy. “Techies think of life as like code,” says Peter Leyden, a Democratic strategist and former editor of the Valley’s original libertarian-leaning tech bible, Wired, “so you just find where the bug is and fix it.” Capitalism and democracy are seen as self-regulating systems that bureaucrats can only screw up. And Paul is the only candidate who understands these killer apps. “What the other candidates say isn’t backed by rational thoughts or facts,” McBride contends.

Libertarian Theology

Libertarian Theology

Libertarianism might be a simple ideology, an aversion to big government in all its forms, but don’t tell that to libertarians: “Like any movement of any size,” says Nick Gillespie, editor of the libertarian magazine Reason, “it is an endless operation of trying to figure out more and more ways in which people who agree on 99.9 percent of everything can really hate each other’s guts.”

Anarcho-Capitalists: The most radical of the lot, they want to abolish government entirely (though, unlike regular anarchists, they do support private property rights). “The state acts like a band of thieves and killers,” explains Lew Rockwell, the best-known exponent of this strain. “The private sector doesn’t do that.”

Minarchists: Archrivals to the anarcho-capitalists, they support a minimalist version of government: Let the state handle roads, policing, and defense—but nothing more. Many, including Ron Paul, view the Constitution as the ultimate minarchist document.

Cosmopolitan Libertarians: Term used by the minarchist editors of Reason to describe their embrace of world citizenship and deride rivals as hayseeds

Economic Libertarians: Worship free-market absolutists like Milton Friedman

Hippie Libertarians: Worship freedom-loving freaks like Larry Flynt

Religious Libertarians: Worship deities of their choosing, care about politics primarily as it affects religious freedom. In 17th-century England they were Puritan Roundheads. In 21st-century America they’re Mormons.

Gold Bugs: Advocate a return to the gold standard, or some equivalent, as a way to diminish the fiscal powers of the state; dismiss foes as “inflationists”

Objectivists: Followers of philosopher Ayn Rand who love morality tales, hate anarchy, and endorse a scorched-earth foreign policy. If “flattening Fallujah to end the Iraqi insurgency will save American lives,” Ayn Rand Institute director Yaron Brook has written, “to refrain from [doing so] is morally evil.”

Neolibertarians: Libertarian neocons; big supporters of the Iraq War

Paleolibertarians: Old-schoolers who despise the neolibertarians for selling out to the system. Also think atheism is overrated.

Technolibertarians: Extropians, transhumanists, sci-fi-fans, they strive to transcend humanity’s meat-puppet limitations and take self-determination to the final frontier.

South Park Conservatives: Find their politics articulated in a show created by two avowed libertarians; a seminal episode follows a race for school mascot between a giant douche and a turd sandwich. Which, says Reason‘s Gillespie, “pretty much sums up how most libertarians approach politics.”

Paultards: Blogosphere dis for those who annoy the online masses by relentlessly shilling for their man in comment threads, polls, and social networking sites

—J.H.

In fact, McBride believes Paul’s reasoning is so ineluctable, written words aren’t sufficient to convey its force. His dvds, culled from clips such as the Google talk and handed out door to door around the Valley, capture Paul in all of his charismatic equipoise. “He just doesn’t get emotionally charged,” McBride says. “He’s very rational. And you can’t always pick that up in an article you are reading. So I think hearing him speak, seeing him speak, can be more influential, more powerful. And people don’t like to read anyways.”

Chants filtered through the second-floor windows of a San Francisco hotel where Paul was giving a speech on fiscal policy at a fundraising breakfast last summer. An hour later the candidate hit the street with an entourage of video bloggers. “The whole city is out here,” a woman pronounced. Paul shook McBride’s hand before disappearing into a thicket of placards. It was the first time McBride had met his idol, and for several minutes he remained frozen on the curb, fumbling to buckle his camera case. “That was a rock-star arrival,” a stubbly hipster in a golf cap remarked. “Oh, bigger than that for me,” McBride gushed.

Paul ambled with a slight hunch across the trolley tracks of Market Street and through the Financial District towing a block-long tail of supporters displaying irony mustaches, man purses, and antiwar banners. “Google Ron Paul!” someone shouted. McBride offered passersby copies of his dvd. (“If you’d told me six months ago that anything would have motivated me to do something like this, I would have told you you were out of your mind,” he later emailed me.)

At the Palio d’Asti restaurant on Sacramento Street, McBride, wearing a ringer T and no jacket, flashed a $500 ticket and walked into Paul’s fundraising lunch. He picked a mostly empty table at the back and pulled out his iPhone, replying to emails from fellow Meetup members who sat at the next table. Then he switched to camera mode, walked over to Lew Rockwell’s table, and wordlessly snapped a photo. “There are a lot of iPhones here,” he told Chris Nelson, a squeaky-voiced computer programmer at our table. “I’ve been keeping an eye out for them,” Nelson said. “Yeah,” McBride confided, “I noticed Lew Rockwell was taking photos with his.”

When the chef brought out plates of Texas wild boar (a Ron Paul special), talk turned from tech to politics. “Isn’t there a whole lot of hope here?” Nelson asked. Paul had a lot of “mainstream support,” agreed McBride. Then the two got in an argument over whether government ever had a role to play—Nelson thought it might be needed to stop global warming, but McBride believed a strict interpretation of private property rights (you can’t pollute my land) would be more effective. “Money is the root of all evil,” McBride said, “but it’s also the solution to everything—economics rules everything. It’s a macro science.”

Just then Paul stood up to speak. His voice was faint. He began by describing himself as the mere servant of a grassroots revolution. He claimed to lack the moral and legal authority to govern, which was why he would abolish most of the federal government. “Some people will say this won’t work,” he said. “They say we need government; if we didn’t have it, it would be total chaos. But it would be the opposite: In some places, we would have more government, but it would be self-government. People would have the responsibility of taking care of their own lives.”

The crowd heartily applauded, though what Paul meant by self-government wasn’t exactly clear. McBride lingered as Paul disappeared for a radio interview; when he reemerged, McBride snapped photos for other Meetup members who’d been unable to afford the entry fee but were now politely queuing up to greet Paul. There, in line, was Nanette LaVogue, a professional “hauntress” with blue hair, and a delegation of medicinal-marijuana advocates who wanted to give Paul an abalone shell. (“It’s still legal tender in Norway!”)

But eventually McBride moved in to chat. “Nice to see…meet you,” Paul said, and McBride delivered the statement he’d composed earlier that day, in all its haiku purity: “I just want to thank you for your hard work and courage.” Then he backed away with a beatific smile.

Later McBride explained why he hadn’t tried to talk further: He already knew what his hero would say on just about any topic. Libertarianism, he glowed, “is the only place where the answers to all questions have actually been resolved.”