Illustration: Andy FriedmanMichigan’s 2010 elections had just concluded, and Rich Robinson, the state’s leading campaign finance reform advocate, was conducting his usual postmortem. As he tallied the big money behind the conservative groundswell that swept Republican Rick Snyder into the governor’s mansion and placed the state Legislature solidly under GOP control, one particular political action committee caught his eye.

Illustration: Andy FriedmanMichigan’s 2010 elections had just concluded, and Rich Robinson, the state’s leading campaign finance reform advocate, was conducting his usual postmortem. As he tallied the big money behind the conservative groundswell that swept Republican Rick Snyder into the governor’s mansion and placed the state Legislature solidly under GOP control, one particular political action committee caught his eye.

Created in December 2009 and shut down shortly after the election, RGA Michigan 2010 had come out of nowhere to spend nearly $8.4 million—54 percent more than any other PAC had poured into any election in Michigan history. Ninety-six percent of the group’s donors lived outside the state, and its top three funders included Texas homebuilder Bob Perry, Koch Industries’ David Koch, and New York City hedge fund CEO Paul Singer. On the other side of the ledger, RGA Michigan 2010 had given $5.2 million to the Michigan Republican Party—no surprise there—but, mysteriously, it had also funneled $3 million into the campaign coffers of Texas Gov. Rick Perry.

Robinson, the executive director of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network, began to connect the dots. He remembered the phone calls from reporters in Maine and Florida asking if Robinson knew why money from the Michigan Chamber of Commerce had ended up with PACs in their states. The state’s Chamber, which usually spent more than $1 million on TV ads during Michigan elections, officially didn’t spend a dime on ads in 2010, according to Robinson. But it had given an unprecedented $5.37 million to a national organization that, Robinson now realized, was at the root of the anomalous spending he’d uncovered: the Washington, DC-based Republican Governors Association.

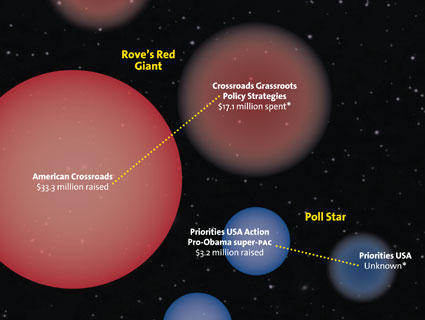

During the midterms, while many campaign finance observers were fixated on the proliferation of super-PACs and shadow-spending groups, the RGA spent $132 million—more than the five biggest conservative super-PACs and 501(c) groups combined. It was instrumental in electing a slate of GOP governors—Wisconsin’s Scott Walker, Ohio’s John Kasich, Georgia’s Nathan Deal, and Iowa’s Terry Branstad, among others—who hastened to crack down on public-sector unions and roll back environmental regulations. These electoral successes were fueled in part by the creative campaign finance strategy that Robinson began to piece together.

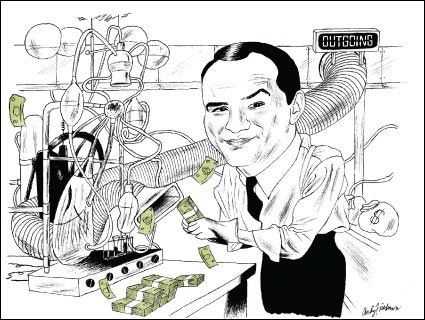

Since 2008, he explains, the RGA has used a network of at least 15 state-level PACs to shuffle campaign cash around the country. Doing so serves a couple of purposes. First, it enables the RGA to scrub the identity of a donor to avoid image issues. For instance, Rick Perry taking $3 million from a Texas oil baron might be controversial, but if that baron gives $3 million to the national RGA, which then diverts the money to RGA Michigan PAC and then to Perry? Harmless.

The RGA’s cash shuffle also allows it—and its corporate allies—to skirt campaign finance laws. For instance, in Michigan, corporations can’t donate directly to candidates or political parties. But the state’s Chamber of Commerce donated millions to the national RGA, which then directed some of the money to its PACs in Florida and Maine, where no such corporate-money bans exist. Why would a Michigan group want its money flowing to races in other states? Chamber CEO Rich Studley told Maine Public Radio that its members supported funding “pro-business” candidates outside Michigan.

Robinson has a different theory. During the 2010 election cycle, the Michigan Chamber donated more than $5 million to the RGA. In turn, the RGA’s Michigan PAC directed $5.2 million—contributions that largely came from individuals outside the state—to the Michigan Republican Party. Robinson believes that, through this roundabout process, the Chamber’s corporate money was swapped out with individual contributions, allowing it to be deployed in Michigan in a more potent form. (The Chamber acknowledges that the RGA called the shots on where its money was spent. Studley says his group’s political spending “has been in full compliance with all Michigan and federal laws.” The RGA did not respond to a request for comment on this practice.)

Robinson and other campaign finance watchdogs liken the RGA’s methods to the corporate-contribution laundering scheme that got former GOP congressman Tom DeLay indicted. “The whole thing,” Robinson says of the RGA’s tactics, “was about wiping the fingerprints off the money.”

An RGA spokesman, Mike Schrimpf, says the group and its network of PACs “aren’t really unique,” but he declined to respond to specific questions. “The RGA and the [Democratic Governors Association] both have to use state PACs in some states to comply with the state campaign finance laws,” he says. The RGA, however, is by far the more powerful of the two, outspending the DGA in the last four election cycles by anywhere from $10 million (2004) to $67 million (2010).

The RGA wasn’t always a political juggernaut. Founded in 1963, the group for decades was content to convene meetings and publish the occasional white paper. That began to change in the early 1980s, when Pennsylvania Gov. Dick Thornburgh became chairman and the RGA started to raise serious money. With the RGA’s backing, the GOP netted seven governor’s seats in the 1986 election.

In 1994, while Newt Gingrich and Co. took control of Congress and rang in the Republican Revolution, the RGA was instrumental in the election of 11 GOP governors and successfully defended every Republican incumbent. When the dust settled, Republicans controlled 30 governorships, their first majority since 1970. The last time Republicans had performed so well in gubernatorial races was 1867.

Beyond its electoral victories, the RGA established itself as a launching pad for Republicans with presidential aspirations. The group helped to foster alliances between GOP governors and gave them access to deep-pocketed donors and top fundraisers, helping to catapult politicians like Ronald Reagan (an RGA chairman), George W. Bush, Rick Perry (twice chairman), Mitt Romney (2006 chairman), and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie (current vice chair) onto the national stage.

The RGA’s rise has been fueled by a close alliance with corporate America—especially tobacco companies and Big Pharma. In the mid-’90s, the organization awarded seats on its board to executives from Philip Morris and R.J. Reynolds, which each donated $40,000 a year. In November 1995, tobacco lobbyists swarmed the RGA’s annual meeting in Nashua, New Hampshire, pressing governors to write letters opposing pending tobacco regulations from the Food and Drug Administration. In exchange for their support, the tobacco companies pledged financial backing when election time rolled around. They came through: In February 1996, Philip Morris held a Washington, DC, gala for the RGA that raised $2.6 million.

The increasing influence of corporate donors turned off some Republican governors, including Arne Carlson, Minnesota’s governor from 1991 to 1999. Carlson recalls attending a few RGA meetings, but he stopped going due to the group’s increasingly partisan tenor and insistence that donors be given access to the governors. “It was no longer Republican governors getting together,” Carlson says. “It was the moneyed interests getting together with governors. I found it detestable.”

In June 2002, the McCain-Feingold Act went into effect, banning federal party committees from raising “soft money”—donations from labor unions and corporations outside the scope of federal campaign finance law. So to keep the corporate cash flowing, the RGA officially broke away from the Republican National Committee (of which it had been an affiliate) and established itself as a 527 tax-exempt group. That way it could continue raising soft money from banks, drug companies, and energy companies. (A few years earlier the DGA had parted ways with the Democratic National Committee for the same reasons.)

Today, RGA’s donor list reads like a who’s who of corporate titans: Koch Industries, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, AT&T, and Pfizer. The organization’s largest donor in both the 2008 and 2010 elections was Perry Homes, the homebuilding empire run by Bob Perry, which plunked down $1.15 million in 2008 and $8 million in 2010.

But as the corporate money gushed in, the RGA ran afoul of the law. In 2008, a top official with the North Carolina state elections board testified that the RGA had illegally funneled contributions to its North Carolina PAC. (The elections board ultimately declined to pursue the matter.) Last October, a Vermont judge ruled that the RGA violated state elections law when it ran ads supporting the Republican gubernatorial candidate without registering as a state PAC. (The RGA argued the spots were merely issue ads.)

In 2012, the RGA promises to be a force to be reckoned with. Led by chief fundraiser Fred Malek, the finance co-chairman of John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign, the RGA had by last fall raised $22 million (twice as much as the DGA) for the 2012 election cycle. Don’t be surprised if that money starts turning up in odd places again, says Mike McCabe, who tracks money in state politics at the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign: “It’s a deliberate strategy to keep the public in the dark about who is really buying our elections.”

Prezi presentation produced by Jaeah Lee