Javier Jaén Benavides

Just hours after the newly Republican Congress was sworn in on January 6, Reps. Trent Franks (R-Ariz.) and Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) introduced a bill that would ban nearly all abortions after a fetus is 20 weeks old. The House of Representatives will vote on the measure—the first in a series of harsh new abortion restrictions Republicans plan to advance this year—on Thursday, the 42nd anniversary of Roe v. Wade.

The party’s congressional leaders and the country’s most prominent anti-abortion rights groups say the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act is their top priority. However, there’s little chance that this bill will overcome a Democratic filibuster in the Senate or a presidential veto. But it could have powerful political consequences—forcing a major new confrontation and pumping up the GOP base in advance of the 2016 election. Eight Republican presidential hopefuls have endorsed the 20-week ban, including Jeb Bush and Sens. Rand Paul, Ted Cruz, and Marco Rubio.

And a 20-week ban could create a major new avenue for directly challenging Roe v. Wade. Since 2010, 12 states have passed similar bans; three have been blocked by lawsuits.* If and when one of those cases comes before the Supreme Court, it could undermine the very framework on which the landmark 1973 decision is built—the notion that women have a constitutional right to terminate a pregnancy at any point before the fetus is viable outside the womb. “There is this temptation to say that these restrictions are just on the edge, that they won’t affect that many women,” says Katha Pollitt, Nation columnist and author of Pro: Reclaiming Abortion Rights. “But they actually strike at the heart of the right to have an abortion. Because it’s a strike on Roe.”

The fight over banning abortions after 20 weeks is as old as Roe v. Wade. (Older, actually—more on that below.) In Roe, the Supreme Court established the right to abortion by forbidding states from banning the procedure anytime before viability, when fetuses can be expected to survive outside the womb. Experts maintain that viability truly begins at 24 weeks after a pregnant woman’s last period, or about 22 weeks after fertilization. (The most rigorous and widely accepted way to date a pregnancy is by counting the weeks since a pregnant woman’s last period. The House bill and the majority of state 20-week bans, however, measure pregnancy from the fertilization of the egg; in medical terms, a 20-week ban is actually a 22-week ban.)

Yet proponents of banning abortion at 20 weeks insist that there are cases of infants born that early who survive. It’s true that since Roe, medical advances have enabled a tiny, yet unknown, number of preterm infants to be born in the middle of the second trimester. But almost none survive. One study found that 85 percent of infants born 20 weeks after fertilization die within 12 hours. Another study found that 98 percent are born with major health issues such as brain hemorrhaging; 93 percent die within a year. The University of California-San Francisco Medical Center states that no infants born earlier than 21 weeks have survived.

Anti-abortion rights groups such as Americans United for Life, which authored several states’ 20-week bans, deny that they are targeting Roe‘s viability rule. Instead, they focus on 20 weeks postfertilization because, they claim, it’s the point at which fetuses experience pain. “Many of them cry and scream as they die,” Franks says. But the scientific consensus roundly rejects this idea: For one, the relay path between the thalamus and the cerebral cortex—the connection that allows the brain to recognize pain—is not fully developed for another six weeks. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says that the developmental milestones at 20 weeks—namely, the appearance of hair—are no more significant than those coming before or after.

The importance of 20 weeks also has its roots in medical beliefs that date back to colonial times. For centuries, it was commonly believed that a woman wasn’t actually pregnant until she could feel the fetus moving inside her. Most states permitted a woman to use potions or instruments to terminate her pregnancy up to the moment of “quickening,” which usually takes place between the 15th and 20th week of pregnancy. By the mid-1800s, most states banned all abortions, but the significance of quickening stuck in the popular imagination. When states began to liberalize their abortion statutes in the 1960s, the typical cutoff was the 20th week of gestation, as in the 1967 California law permitting some abortions signed by Gov. Ronald Reagan.

And quickening remained an important legal concept. In 1970, a federal district court in Wisconsin ruled that the state could not interfere with a woman’s decision to terminate until she was carrying a “quick” fetus. As the Supreme Court prepared to hear arguments about absolute abortion bans, Illinois lawmakers moved to update the state’s near-total abortion ban with a 20-week ban that would survive in the event that the Supreme Court legalized abortion up until quickening.

Unexpectedly, Roe v. Wade dismissed quickening and instead focused on viability. The Supreme Court noted that average viability began at 28 weeks (the start of the third trimester), but that it was possible for fetuses to be viable as early at 24 weeks. The justices left it up to doctors to determine viability in individual cases. States, they ruled, could not set a date for viability. (In a later ruling, the Supreme Court did away with its original trimester framework.)

But anti-abortion advocates weren’t ready to give up the 20-week line. Immediately after Roe, states debated a flood of bills aimed at imposing restrictions at 20 weeks, says Jill E. Adams, the executive director of the Center on Reproductive Rights and Justice at the University of California-Berkeley School of Law. Twenty weeks, Adams notes, was a nice round number to present to the public, although pro-life legislators vacillated between the two definitions of “20 weeks.” In the years after Roe, New York required a second physician to be present at any abortion performed after 20 weeks in case the fetus lived and required intensive care. Illinois required every abortion performed after 20 weeks to be recorded publicly until 1978; its 20-week ban stayed on the books until the 1980s.

In 1984, these bills became a formal strategy for defeating Roe. That’s when a Northwestern University law professor named Victor Rosenblum proposed that abortion opponents should seek to pass laws that gnawed at its edges, and hope that judges would let those revisions stand. The so-called incrementalists notched their biggest victory in 1989, when the Supreme Court upheld parts of a controversial Missouri law that required doctors to perform costly viability tests before performing abortions for women who appeared to be at least 20 weeks pregnant. The case, Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, demonstrated just how powerful a weapon a 20-week measure could be. Justice Thurgood Marshall’s papers revealed that the conservative majority in Webster had come within one vote of using the 20-week provision to strike down Roe entirely. The liberal justices went as far as drafting a dissent that read, “Roe no longer survives.”

Samuel Lee, who wrote that provision of the Missouri bill while he was a lobbyist for Missouri Citizens for Life, says the 20-week requirement “was designed as an opportunity to attack [Roe]” and the viability framework it established. “The 20-week gestational age was chosen to push the envelope on when the state’s interest in protecting the life of the unborn could take place,” he explains. “It was chosen because it was earlier than the earliest limits of viability at the time, but not so early that the unborn child could never be viable.”

Lee’s bill counted 20 weeks from a woman’s last menstrual period. Pro-lifers today would call it an 18-week abortion restriction. But the Webster ruling was reported as a 20-week measure, and the date stuck. A rash of copycat bills, as well as bills banning abortion at 20 weeks postfertilization, followed. Some tried to push the envelope further: Utah required doctors who performed abortions 20 weeks after conception to use a method most likely to allow a viable fetus to survive. (A federal court struck that law down.) Connecticut lawmakers debated a bill that would require proper burials for aborted fetuses 20 weeks or older.

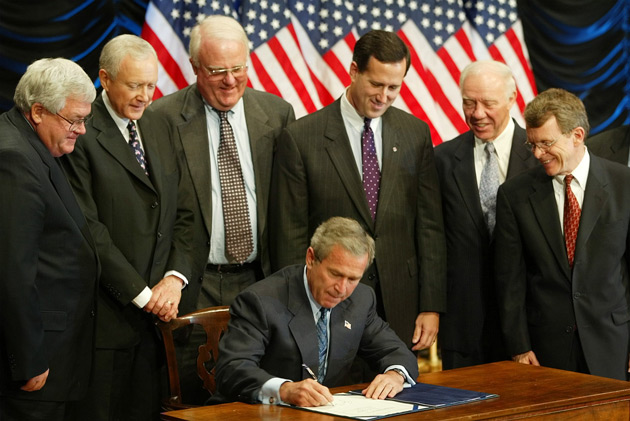

The deluge of 20-week restrictions culminated in Congress’ first abortion showdown since Roe: the Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act. Bill Clinton vetoed it in 1995 and 1997, but President George W. Bush signed it in 2003, outlawing a procedure, commonly used 20 weeks after a woman’s pregnancy, that had been used in about 2,200 out of the 1.3 million abortions performed at the time. The bill was heralded as protecting viable infants by pro-life advocates who conflated 20-week old fetuses with 20-week old pregnancies. Twenty-week old fetuses “look like babies,” observed Douglas Johnson, the legislative director for the National Right to Life Committee. “We’re talking about individual premature infants, is essentially what we are talking about,” he said. By this point, the fetal-pain argument had also taken hold, thanks to the 1984 film The Silent Scream, which purported to show a fetus contorted with pain.

“All of these different tactics, all of these different theoretical persuasions, they’re all linked,” says Adams. “The original 20-week bans, or efforts to pass those bans, were predicated not on the notion that a fetus was pain-capable but the desire to make abortions as difficult to procure—and ultimately impossible to procure—as possible.” The ultimate goal wasn’t to simply erode Roe but to explode it.

“I’VE ALWAYS WANTED A BABY for as long as I can remember. Even when I was a kid,” recalls 29-year-old Elizabeth. “Even when I was in day care, when I was three years old. When the kid’s parent came to pick them up, I was the one to go get the kid, to put them in their jackets, to walk them to the door.”

Last year, Elizabeth, who asked that I not use her last name, was thrilled to find out that she was pregnant. It was a girl, whom she named River. “And everything was normal up until I was 20 weeks pregnant.”

Then, a routine ultrasound revealed fluid building up in the fetus’s skull like water behind a kink in a hose. The condition, which occurs in 1 in 500 pregnancies, is known as hydrocephalus, and it can destroy the brain in utero. After 10 more wrenching weeks, another scan confirmed the worst: There was almost no brain left. If Elizabeth delivered River right away and she survived, the infant would undergo weeks of grueling surgery, yet would never develop even the most basic mental functions.

Tennessee, where Elizabeth lives, had no providers that perform abortions at 30 weeks. So she and her husband put their baby gifts in the attic and drove 20 hours to Denver. By the time she got an abortion, Elizabeth was 33 weeks pregnant. “I don’t have any regrets,” Elizabeth told me. “It might have been hard for us, but it was the right thing to do for her.”

Although the House Republicans’ bill makes exceptions to preserve the life or health of a woman and for victims of rape or incest (though only if they report the assault to law enforcement), it makes no allowance for women like Elizabeth, who seek abortions because of devastating fetal anomalies that often cannot be detected before a 20-week ultrasound.

Women who end their pregnancies after 20 weeks’ gestation account for less than 2 percent of all abortions performed in the United States—a figure that has been static since the early 1970s. About 13,000 women sought these later abortions in 2011, the most recent year for which there is reliable data. Solid data on why women seek abortions after 20 weeks is scarce. What is known is that majority of women who terminate their pregnancies because of fetal anomalies, like Elizabeth, do so after the 20-week mark. Researchers say that most women who have abortions after 20 weeks do so because they didn’t have the money for an earlier abortion; they experienced a disruptive life event such as divorce, abuse, or the death of a partner; or they didn’t realize they were pregnant. That last category includes teens who don’t have a regular period or who don’t recognize the signs of pregnancy.

Abortion opponents have used this information to suggest that women who have late abortions are irresponsible. “It’s important to keep in mind that the vast majority of late-term abortions are performed on healthy mothers, on healthy babies,” says Maureen Ferguson, a senior policy adviser for the conservative Catholic Association. Her group has called these abortions “inhumane.””People don’t like the idea of late abortions,” Pollitt says. “It’s hard to mobilize sympathy for that.” The proposed ban, she continues, will appeal to “people who don’t know anything about what women go through to get an abortion.”

Yet the women who have been most vocal in opposing these bans are those who ended wanted pregnancies for health reasons or because of fetal anomalies. That’s one reason why the current House bill could rekindle the idea that Republicans are waging a “war on women.” Chris Lehane, a Democratic strategist who works out of California, notes that the GOP’s anti-abortion antics have fired up younger female voters about an issue that was once an afterthought for many. Perhaps anticipating this, the Republicans are planning to dispatch mostly female lawmakers to debate the bill on the House floor, Politico reports.

“Does pushing [the ban] help some individual Republicans in conservative states who don’t want to get primaried? Yes,” says Lehane. “But does this help Republicans as a national party—a party with the ability to compete in purple states? No.” But as long as the party’s base insists on rolling back abortion rights, “you default back on the plays you used to run.”

Correction: This story originally stated that 20-week abortion bans in three states have been blocked by federal lawsuits. In fact, one of the bans is blocked by a state lawsuit.