John Lott speaks at a gun rights rally at the Connecticut State Capitol in April 2013, four months after the Newtown shooting.Jared Ramsdell/Journal Inquirer/AP

When you watch the news after the latest big shooting, there’s a good chance you’ll come across John Lott. The 57-year-old economist has made more than 100 media appearances over the past two years, from friendly conversations on Fox News to heated debates on MSNBC and CNN. After nine churchgoers were gunned down in Charleston, South Carolina, he went on Sean Hannity’s show and criticized President Obama for spreading “clearly false” information about gun violence. Following the recent mass shooting in Chattanooga, Tennessee, his op-ed asking “Why should we make it easy for killers to attack our military?” was among the most popular articles on the Fox News site. After an interview with Lott in the wake of the movie theater shooting in Lafayette, Louisiana, conservative radio host Laura Ingraham gushed, “He knows more about guns and the Second Amendment than pretty much anyone I know.”

Lott does not come off as the stereotypical pro-gun activist. His demeanor is professorial and his argument is academic: Based on his years of research and data analysis, he claims that guns reduce crime by enabling people to protect themselves and deter criminals. His message is simple: As he told CNN’s Piers Morgan in the wake of the Aurora mass shooting, “Guns make it easier for bad things to happen. But they also make it easier for people to protect themselves and prevent bad things from happening.” His book, More Guns Less Crime, which has been referred to as the bible of the gun lobby, forms the quantitative justification for the effort to ease restrictions on concealed firearms across the country.

It’s no coincidence that Lott’s profile has risen as Americans have been reckoning with the causes and impact of gun violence. But his newfound visibility is surprising considering that, a dozen years ago, his professional reputation was in tatters, his bold claims undermined by accusations of shoddy research and questionable ethics.

Lott first stepped into the limelight in 1997, when, as a research fellow at the University of Chicago, he cowrote an econometrics study that concluded that counties that permitted the concealed carrying of firearms had lower crime rates. A year later, Lott released the first edition of More Guns Less Crime. He quickly gained a name as a “reputable” and “distinguished” scholar, says Philip Cook, a Duke economist whose own findings contradict Lott’s. Lott’s early work “was light years ahead of anybody else at the time,” says Gary Kleck, a criminologist at Florida State University who wrote a glowing review of the first edition of Lott’s book.

Pro-gun politicians and pundits latched onto Lott’s arguments. In the five years following the book’s publication, Lott testified in favor of concealed-carry laws before Congress and at least five state legislatures. Idaho Sen. Larry Craig cited Lott when he introduced a bill to loosen restrictions on gun owners crossing state lines. In 2003, 18 state attorneys general mentioned his “empirical research” in an open letter to then-Attorney General John Ashcroft. The website of the NRA Institute for Legislative Action cites Lott and his work more than 140 times.

Yet as Lott’s profile rose, his work came under scrutiny. The National Research Council, a branch of the National Academy of Sciences, assembled a panel to look into the impact of concealed-carry laws; 15 of 16 panel members concluded that the existing research, including Lott’s, provided “no credible evidence” that right-to-carry laws had any effect on violent crime. Economists Ian Ayres of Yale University and John Donohue of Stanford University argued that Lott had drawn inaccurate correlations: Cities had experienced a spike in crime in the 80’s and 90’s in part because of the crack epidemic, not because of strict gun laws. When they extended their survey by five years, they found that more guns were linked to more crime, with right-to-carry states showing an eight percent increase in aggravated assault.

Kleck reexamined Lott’s work and found that he hadn’t accounted for missing data. “It was garbage in and garbage out,” he says. Even Kleck, who conducted a controversial, yet often-cited survey on defensive gun use, observes, “Do I know anybody who specifically believes with more guns there are less crimes and they’re a credible criminologist? No.” David Hemenway, the director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center, has concluded that “virtually all of Lott’s analyses are faulty; his findings are not ‘facts’ but are erroneous.” Lott maintains that the missing data Kleck refers to had no impact on his final conclusions, and that the “vast majority” of economists and criminologists support his findings.

Researchers pressed Lott, then a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, to release the data behind his claim that 98 percent of defensive gun uses in the United States involved a would-be victim merely brandishing a gun. Lott claimed that it was based on a data from a survey he had conducted—but that the data had been lost in a computer crash. Lott redid the survey in 2002; of more than 1,000 people surveyed, seven said they’d used a gun to defend themselves. Of those seven, six merely flashed a firearm in self-defense. Based on these responses, plus the lost data, Lott still asserts that more than 90 percent of defensive gun uses involve brandishing a gun.

As criticism of Lott mounted, an online commenter, who identified herself as a former student of Lott’s at Penn named Mary Rosh, lavishly praised her former professor and attacked his critics. “He was the best professor that I ever had,” she wrote. After it came out in 2003 that Rosh and Lott shared an internet address, Lott admitted to the sock puppetry, saying that he had been receiving obnoxious phone calls when using his real name, and some of Rosh’s comments were possibly written by his family members on a shared email account. “In most circles, this goes down as fraud,” wrote Science editor-in-chief Donald Kennedy in the magazine. And yet, he observed in a blistering op-ed, “Legislators in a number of states are still considering liberalizing concealed-weapon laws, and Lott’s book plays a continuing role in the debate. That moves this story from high comedy to a troubling challenge in social policy that isn’t funny at all.”

Lott is no longer affiliated with any university. Now when he appears, he’s introduced as the president of the Crime Prevention Research Center, a nonprofit he founded in 2013 to study the relationship between gun laws and crime. The organization, headquartered at his home in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, produces and publishes “academic quality” reports that have yet to be published in peer-reviewed journals, but are, according to Lott, informally reviewed by the organization’s academic board. “If they have comments, while there is no formal review by them, they let us know,” he explains in an email. The center’s reports have been cited by the New York Times, the Boston Globe and other major publications.

The editors and producers who turn to Lott for stats and soundbites seem unconcerned by his baggage. A person who has recruited Lott for TV appearances says his appeal is simple: “He’s got a controversial position and he’s smart. What more could you want?” Besides, as Kleck explains, “All that discrediting is based on technical issues that people don’t understand or care about.”

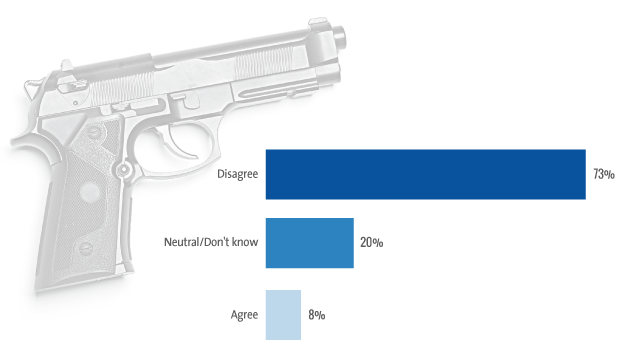

Hemenway, the Harvard researcher, likens the way the media handles Lott to its treatment of climate change skeptics (of which Lott is one). After the mass shooting in Newtown, Hemenway recalls reading news articles in which he was quoted on the efficacy of gun control: “They would end up with a ‘he said, she said’—’David Hemenway says such and such,’ and one of the small number of very pro-gun researchers like Gary Kleck or John Lott would say something. The reader would think, ‘Okay, so there’s disagreement this.'” Hemenway has surveyed gun researchers, finding that only nine percent of those asked believe that more lenient gun laws reduce crime.

In April, the CPRC held a fundraiser in Nashville, Tennessee, to coincide with the NRA’s annual convention. Supporters received plastic ducks printed with the slogan “Gun-free zones turn people into sitting ducks.” Wonky and unflappable as ever, Lott addressed his donors. “The debate among academics is among those who say there’s a benefit [to carrying guns] and a smaller group who say there’s no effect,” he said. “Nobody is seriously really arguing that it increases murders.”

Following Lott, Ted Nugent took the podium. “The only good rapist is a dead rapist,” the rocker and CPRC board member stated, to applause. Conservative radio host Dana Loesch also stepped up to praise Lott. “Without John Lott and his mathematician’s mind and love of numbers, we would have to go through a lot more data by ourselves,” she said. “We don’t have anybody else on our side that does what he does.”