Photo by Tim Murphy

Donald Trump’s preparation for the upcoming Republican presidential primary debate is “low key, absolutely low stress,” adviser Chuck Laudner told the Washington Post on Wednesday. “This isn’t 50 consultants locked in a war room, with a fake podium and cardboard cutouts of the other candidates, playing the game of Risk.”

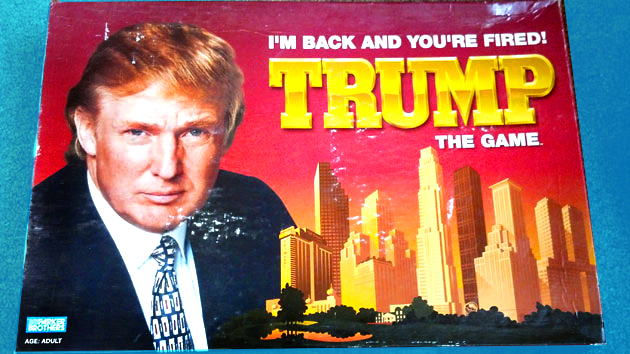

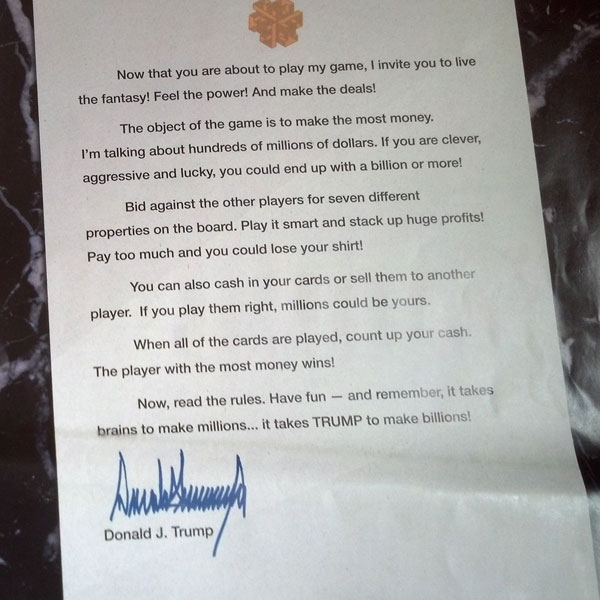

Maybe that’s because Trump has a different board game of choice—his own. In 2004, as his reality television show The Apprentice was just getting underway, he unveiled the latest in a long line of short-lived ventures. (Hello, Trump Steaks.) It’s called TRUMP: The Game, and according to an introductory letter from the billionaire that was included in a set I recently acquired for $4 on Amazon, “the object of the game is to make the most money.” Surprise!

Live the fantasy! Feel the power! And make the deals! Photo by Tim Murphy

Much like his presidential campaign, TRUMP: The Game was a reboot of an earlier failed Trump venture, a 1988 Milton Bradley product also called TRUMP: The Game. The tagline for that was “It’s not whether you win or lose, it’s whether you win!” A television ad for TRUMP: The Game 1.0 boasted that all proceeds from the game would be donated to charity. (This was his Paul Newman phase, evidently.) The 2004 version abandoned the charitable pretense, and replaced the old tagline with a bolder, fresher take: “IT TAKES BRAINS TO MAKE MILLIONS. IT TAKES TRUMP TO MAKE BILLIONS.”

Did I have the brains to make millions? Did I have the TRUMP to make billions? Was I, in fact, Donald Trump? I recruited three Mother Jones political reporters—Pat Caldwell, Pema Levy, and Molly Redden—to help me take TRUMP: The Game for a spin.

Here are a few things you should know about the game:

- It’s for three to four players. Cramped and short-lived—it’s the Trump Shuttle of board games. This is a great game if you don’t have very many friends.

- The box specifies that TRUMP: The Game should only be played by adults. (If you are a child reading this, please stop now.) What? Is this is a board game about pre-nups? Is scalp-reduction surgery involved? If it’s for adults, why is an oversized six-year-old on the cover? I kept waiting for the game to reveal some darker, truer, more adult nature, but it never did.

- The dice have six sides. Five of the sides have the traditional numbers on them. But the sixth side just has a big letter T on it, for “Trump.” Anytime you roll a “Trump,” you get to steal something from someone else.

- But you don’t roll the dice very often—maybe once every few turns, depending on your strategy. TRUMP: The Game borrows the architecture of a classic game, Monopoly, and then renovates it until there’s nothing left but a flashy facade.

- The most exciting part of the game is bidding on properties. Like Monopoly, you buy properties and try to make money off of them. Trump recommends buying as many properties as you can! But there are only seven properties (including a luxury residence, an international golf course, and a casino—only the finest and most luxurious properties are for sale here), so you can’t really do that. It’s not possible, either, to simply attach your name on the side of someone else’s building in big letters and just own a penthouse there.

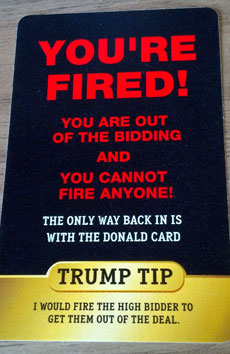

- When a property goes up for sale, players take turns raising their bids or taking a pass, until someone has outbid everyone else. Then that person own the property. Unless someone else ejects that person from the bidding by playing a card that says “You’re fired!” (Actually it says, “YOU’RE FIRED! You are out of the bidding and you cannot fire anyone!” Since when can people who have just been fired fire other people?)

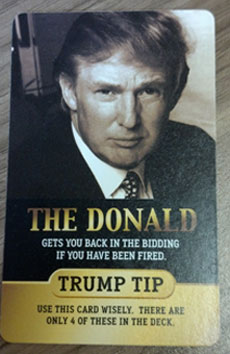

- If you’ve been fired, you can get back into the bidding by playing a special card featuring Donald Trump’s face. This is, for some reason, not called “the Trump Card.” Instead it’s called a “The Donald”—definite article included. Like “The Gambia.” There are 16 You’re Fired! cards but only four The Donalds, meaning that bidding wars often consist entirely of people playing the “You’re Fired!” card over and over and over. The unemployment rate in Donald Trump’s game is 75 percent. I don’t know why you can fire people who don’t even work for you. But this is how capitalism works.

- Instead of paying taxes to the government, there is a card that, if played, forces other players to pay property taxes to you. (“Trump Tip: I would play this on someone with more than one property.”) That is not a tax. That is just a shakedown.

- At the end of the game, the person with the most money wins. Fair. What’s weird is that there’s basically no way to lose money, short of occasionally paying taxes to other people. Instead of losing money when you land on properties owned by rivals, as in Monopoly, you take money from the bank that doesn’t belong to you (don’t worry about paying it back) and give that money to the player who owns the property. All overhead costs are covered by the banks. The result: the bank is sinking much of its money into a giant real-estate bubble. What could go wrong?

- Trump, apparently pressed for time, borrowed the color-coded currency from Monopoly—the lowest denomination is white; the middle is green; the highest is orange. The major difference is that the lowest denomination is $10 million and the highest is $100 million. He basically took Monopoly money, stuck his face on it, and added a bunch of zeroes.

Our experimental game lasted a little more than an hour. If there’s an upside to TRUMP: The Game, it’s that it’s hard to envision anyone flipping the board over in disgust after six hours because it’s physically impossible for a game to last that long. At no point did anyone have any idea who was winning until Molly bought the casino. Luxury properties are Trump’s horcruxes; when the seventh one is taken off the board, the game ends. Molly won.

“I’m Donald Trump now,” she said. For a brief moment, I thought I saw a shadow fall across her face.

Afterwards, I asked our team of guinea pigs for their feedback:

“It’s like Monopoly, but really dumb,” Pema declared.

“Nothing really happens,” Pat said. “I think I probably went around the board twice.”

“The thing about it is,” Pema continued, “it’s just a dumb game. Because you can’t really lose money. In Monopoly you can get really screwed by landing on other people’s properties. In this there’s very little moving around the board. And when you land on a property, the bank pays them instead of you so there’s no real risk.”

But the game’s flaws—its erratic nature, its contradictions, its singular obsession with the rapid accumulation of wealth for the purpose of acquiring luxury real estate and firing people—are also Trump’s flaws. And by the time we’d finished, there were a few signs that the experience of playing Donald Trump had begun to influence us in subtle ways. “I could see us all becoming ruthless and judging each other,” Pat said, after a moment of reflection. And more to the point, handling such huge quantities of money seemed to bring us closer, if just a little bit, to the luxurious lifestyle of the Republican front-runner. As Molly put it: “I stopped saying ‘million’ after a while and started treating them like normal denominations.”

Just don’t ask any of us to play it again.