The Endangered Species Act has been one of the country’s most valuable environmental tools, but it faces new threats. As the law turns 50, we’re asking whether this “pit bull” of an environmental law, as one expert described it, can survive the challenges of our time—from political attacks to climate shocks. You can read all the stories here.

The Sonoran pronghorn is an impressive beast. The antelope-like mammal, with its forked horns and eyes as powerful as binoculars, can dart at speeds of about 60 miles per hour—making it the fastest animal on the continent. It’s the only species of its family, Antilocapridae, to have survived a post–Ice Age extinction event about 11,000 years ago that wiped out 70 percent of large mammals in North America. But the pronghorn, nicknamed the “desert ghost,” is also extraordinarily rare. After years of overhunting and habitat loss, plus a devastating drought, by 2002 just 21 individual pronghorns remained in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona, the animal’s last population in the United States.

None of these details deterred Rep. Andy Biggs from introducing a measure that would have dealt another blow to the species. In July, the Arizona Republican, a member of the far-right House Freedom Caucus, introduced an amendment to the defense spending bill to end federal protections for endangered species on US military lands. As a card-carrying beneficiary of the Endangered Species Act for the last 50 years, the pronghorn and its pesky protection plan were interfering with US military operations, Biggs argued, including the firing of live missiles on the Barry M. Goldwater Range, an Air Force base in his state.

“If biologists determine that the Sonoran pronghorn is present within three miles of the training range,” he thundered from his podium during a House floor debate on the National Defense Authorization Act, “they shut it down.” (The range’s public affairs office did not respond to a request for information from Mother Jones.) Biggs hoped his amendment would exempt the Pentagon from complying with the ESA entirely—a drastic change that would affect not just the pronghorn, but hundreds of species that live on 27 million acres managed by the military. It’s “crazy,” a Democratic staffer for the Natural Resources Committee told me. “That’s a huge chunk of the economy to just be fully exempt.”

Biggs’ strategy—sticking a rider to must-pass legislation like the NDAA (a bill that Congress passed last week, after months of negotiation)—is hardly original. But it has been uniquely effective for the GOP. Rather than amending the ESA directly, which could draw public scrutiny and debate, in the past decade or so, experts tell me, congressional Republicans have taken a more behind-the-scenes approach to unraveling one of the country’s most powerful environmental laws—often one species at a time. “The act has been under attack a lot more in the past couple of years than we’ve seen for a long time,” says Joe Roman, a conservation biologist and author of the 2011 book, Listed: Dispatches from America’s Endangered Species Act. Among his biggest concerns is the increasing use of legislative riders that often have little to do with the bills to which they’re attached.

Last year, for instance, Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine successfully tacked on an amendment to the 2023 government funding bill to remove protections for the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, a move intended to benefit lobster fishers. This year’s House Interior appropriations bill includes riders that would block protections for species like the northern long-eared bat, bison, and the lesser prairie chicken (a repeated target for Republicans), which is threatened by oil and gas development. Roman worries that one of the whales he studies, the Rice’s whale, will be next. There are 50 or fewer full-grown Rice’s whales left in the Gulf of Mexico; if the animal is granted habitat protection by the ESA, those measures could hinder oil drilling in the Gulf. When there’s a conflict between endangered species and industry, Roman says, “I’m afraid that we’re going to keep seeing these riders introduced.”

As Roman explains, there are two major benefits to this strategy. Riders draw less public attention than bigger bills. Plus, lawmakers can write into a rider that the rule is not subject to judicial review, meaning a court couldn’t change it. And they’re on the rise: According to the Center for Biological Diversity, between 1996 and 2010, lawmakers launched 69 attacks against the ESA, an average of about 5 per year (just two of which were riders). From 2011 to 2022, attacks jumped to an average of more than 37 per year, peaking at 88 attacks in 2015, when Republicans controlled both the House and the Senate. At the time, the Center concluded that about a third of lawmakers’ attacks on the ESA were made via legislative rider. “These riders have no relevance to the spending priorities of Congress, but are nonetheless added through secretive closed-door processes as a means to pass controversial provisions that would otherwise not pass as standalone bills,” the group wrote in 2015. “There is no public hearing, debate, or citizen involvement.”

In July, Biggs’ measure failed, 193-237. Two hundred and twelve Democrats and 25 Republicans voted against it. But the fact that he’d proposed such a drastic measure at all and that so many Republicans signed onto it represents a marked shift from just a few years ago, Democratic lawmakers tell me. And it may offer a grim preview of what’s to come should Republicans control Congress. “There really aren't even words to describe how radical and extreme that is,” Rep. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.), said about Biggs’ amendment. “But the fact that most—pretty much all—of my Republican colleagues just fell in line and voted for that tells you a lot about where we are.”

When it became law 50 years ago, the Endangered Species Act was considered a historic, bipartisan achievement. The law sailed through the House in 1973, passing 390-12, and not a single senator voted against it. As Republican President Richard Nixon signed it into law, he issued a statement that many Republicans today wouldn’t be caught dead uttering: The country’s wildlife, he said, was a “many-faceted treasure” and “a vital part of the heritage we all share as Americans."

The truth is, Nixon was less a conservationist than an opportunist. At the time, environmentalism was popular, even among Republicans. The late 1960s was a period of acute and visible environmental turmoil in the US. Pollution in Lake Erie reached an all-time high; Ohio's Cuyahoga River was so saturated with oil pollution that it appeared to catch fire; and the nation saw what was at the time the worst oil spill in US history in Santa Barbara, California. All sorts of “charismatic megafauna”—condors, whooping cranes, right whales, jaguars, and more—were approaching extinction. “We were wiping out all kinds of species of fish and wildlife and didn’t seem to realize what we were doing to ourselves,” former House Representative John Dingell (D-Mich.), the longest-serving member of Congress in history and a sponsor of the ESA, told me in 2018 when he was 92-years old. Nixon, to his credit, sought to address those environmental ills: During his six years in office, he also signed the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Marine Mammal Protection Act, among other environmental laws, and established the Environmental Protection Agency. Of them all, the ESA was considered the “crown jewel” of America’s environmental laws. But along the way, it lost favor among many Republicans and has since become, in their eyes, something of a political whack-a-mole.

The shift began with one small fish. In 1973, scientists discovered a new species, the snail darter, in the Little Tennessee River, which was also the site of the nearly completed, $116 million Tellico Dam. At the time, Roman explains, it was the only place on Earth known to host the fish. If the dam were to be completed, scientists believed it would wipe out the entire species. The question of whether the dam could be built went all the way up to the Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously in favor of the fish. “The snail darter controversy focused the nation’s attention—and the ire of industry, small government, and pro-development advocates—firmly on the ESA,” historian and lawyer Lowell E. Baier writes in his book Codex of the Endangered Species Act. Republican lawmakers from Tennessee funneled that ire into a rider on an energy and water appropriations bill that nullified the Supreme Court ruling, and the Tellico Dam was eventually completed. The snail darter population in the Little Tennessee River disappeared for a time. (Interestingly, as Roman writes in Listed, future vice president and environmental advocate Al Gore, then a young lawmaker from Tennessee, voted in favor of the dam construction, which promised to bring 6,600 jobs to the region. He called the delay of the dam “unfortunate” when it was “virtually finished.” Newt Gingrich, then–newly elected as a Republican representative from Georgia, voted for the fish.)

But in those days, Republicans’ contempt for the ESA was still at a simmer. When President Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, the simmer reached a full boil. He issued an executive order requiring an economic review of all major government regulations, effectively putting funding for the ESA and other laws on hold. “The picture changed under Reagan,” Lee Talbot, a member of Nixon’s Council on Environmental Quality and a co-author of the Endangered Species Act, told me. (We also spoke in 2018; Both Talbot and Dingell have passed away.) “What had been a situation where the Democrats and the Republicans worked together—Reagan killed that. And I’ve never forgiven him for it.” Around the same time, Baier explains, litigious, pro-environmental groups formed, including the Center for Biological Diversity, Western Watersheds Project, WildEarth Guardians, and others, aiming to force the federal government into action with lawsuits, which only fueled more controversy among landowners, ranchers, farmers, and other industry-minded Americans. To this day, Baier estimates, the ESA is involved in more lawsuits than any other federal law.

Then came the northern spotted owl controversy. In 1990, not long after President George H.W. Bush took office, the federal government designated the owl as a threatened species, meaning it was at risk of becoming endangered. Biologists established nearly 7 million acres of timber forest as critical habitat for the species—a decision which cut an estimated 32,000 jobs—and sparked the ire of the timber industry and the Pacific Northwest communities that relied on it economically. As Baier writes, logging families and their supporters protested the listing, often by holding rallies "featuring slogans such as 'Save a Logger–Eat an Owl,' 'I Love Spotted Owls–Fried,' and 'Save the Trees–Wipe Your Ass with a Spotted Owl,'" to name just a few. The ESA had officially broken the country in two.

Over time, as the tensions between industry and environmentalists deepened, Republicans and their supporters increasingly saw the Act as an example of government overreach. Why should one species, the argument went, stand in the way of economic growth?

By the Obama years, this argument opened the door for Republicans to embrace a strategy of rolling back the ESA one plant or animal at a time. In 2011, for the first time, Congress directly removed a species from the endangered species list by legislative rider. With an amendment to the federal budget bill, lawmakers Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.) and Rep. Mike Simpson (R-Idaho) ended protections for wolves in Montana and Idaho. As Defenders of Wildlife's Michael T. Leahy, told the New York Times, “Now, anytime anybody has an issue with an endangered species, they are going to run to Congress and try to get the same treatment the anti-wolf people have gotten.”

Leahy was right. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, in the 15 years before 2011, lawmakers made just 16 species-specific legislative attacks. In the five years after 2011, that number jumped to 102. And not-so-curiously, the animals most often targeted—wolves, sage grouse, the American burying beetle, lesser prairie chicken, Delta smelt, and Sacramento River salmon—tended to have something in common: Their existence interfered with oil, gas, or agricultural operations. Wolves have been a pain for ranchers because they feed on livestock, while the American burying beetle lives on prime oil-drilling lands.

But if Tester and Simpson sparked a fire under the ESA, Citizens United v. FEC supplied the fuel. The 2010 Supreme Court case opened the door for corporations to legally contribute unlimited funds to political candidates, so long as the money was funneled through an outside group. And companies certainly took advantage of that freedom: Between 2008—the last election year before Citizens United—and 2022, political contributions by Big Ag to members of Congress jumped from $74 million to $128 million, and oil and gas political contributions tripled from $44 million to $133 million.

Biggs is among the beneficiaries. Although he’s relatively new to Congress, elected in 2016, he’s since won the support of donors like Koch Industries, a multi-sector conglomerate with a long history of lobbying against environmental policy; utility companies Pinnacle West Capital and Salt River Project; and the aircraft-manufacturing behemoth Boeing. And he’s been busy: He has so far sponsored more bills this session than any other member, including at least five bills intended to weaken the ESA.

By the time Trump took a seat in the Oval Office, the ESA itself was already more endangered than ever. And Trump twisted the knife. During his four years in office, the Trump administration issued regulations that stripped automatic protections for threatened species, allowed economic factors to be considered in species listing decisions, and made it harder to protect species threatened by climate change. In 2018, when I asked Talbot whether he was confident the Act would be around in the coming decades, he replied, “Given the present administration, I’m not confident in anything.”

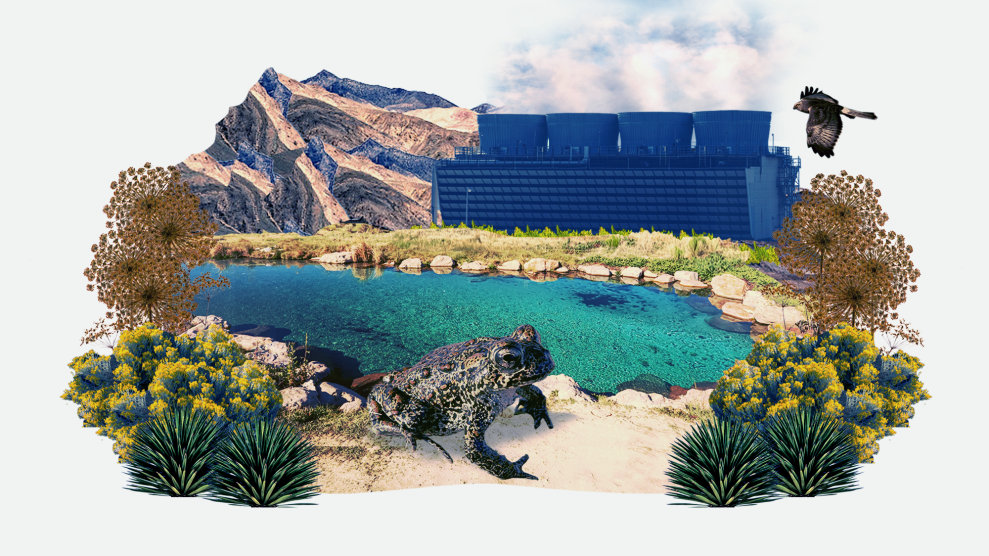

For the pronghorn, the Endangered Species Act has been a lifeline. In the two decades since the pronghorn’s numbers hit an all-time low of 21, the species’ wild population now sits at several hundred animals, thanks to a captive breeding program and other conservation measures brought forth by its listing under the ESA. The pronghorn still has a long road ahead to recovery, but today, its future, in the words of the Fish and Wildlife Service, looks “relatively sunny.”

Other species may never get a chance to bounce back. In June, the Fish and Wildlife Service announced it was considering a listing for an extremely rare southwestern species, the dunes sagebrush lizard. But, unfortunately for the lizard, its range overlaps with the Permian Basin in southeast New Mexico and western Texas—home to one of the highest-producing oil fields in the US. In July, during a Republican-led House oversight hearing titled, “ESA at 50: The Destructive Cost of the ESA,” Rep. Lauren Boebert (R-Colo.) asked Fish and Wildlife Service director Martha Williams about the dunes sagebrush lizard, and why her agency wants to “burden landowners with onerous ESA-related prohibitions” when the agency has “insufficient information to support a listing” for the lizard. Rep. August Pfluger (R-Tex.) called the lizard’s proposed listing “an attack” and “a weaponization of a federal agency, specifically against the most prolific energy-producing region in the world.”

“Was this species listed in an attempt to kill the fossil fuel industry?” he asked Williams.

“Absolutely not,” she replied. Williams said she had spent “a career” working on the dune sagebrush lizard, and the science was “very clear” on why a listing was needed, pointing to the “irreversible” loss of its habitat, shinnery oak dunelands. Although oil and gas companies had spent millions in voluntary conservation efforts, those efforts were “not enough” to prevent a listing, she said.

Their lobbying, however, just might. A week after Republicans’ oversight hearing, the House unveiled its Interior appropriations bill for 2024, and written into it was a provision blocking the Fish and Wildlife Service from using any funds to list the dunes sagebrush lizard as threatened or endangered, along with riders that blocked protections for at least six other imperiled species. In November, it passed the House 213–203, with just three Republicans voting against it. (The Senate has yet to pass its version of the appropriations bill.)

Rep. Dan Newhouse (R-Wash.) celebrated the House bill, boasting that it blocked “overreaching regulations under the Endangered Species Act.” “This year’s Interior appropriations bill is a win for western and rural America,” he said, “and our fiscal future.”

In a grim sense, he’s right: As one of more than 215 House Republicans to receive a combined total of nearly $36 million in contributions from oil, gas, or agricultural interests in 2022, Newhouse and his colleagues’ fiscal future looks very bright indeed. But for the country’s imperiled animals who have unknowingly interfered with industry interests, the future is growing dimmer.