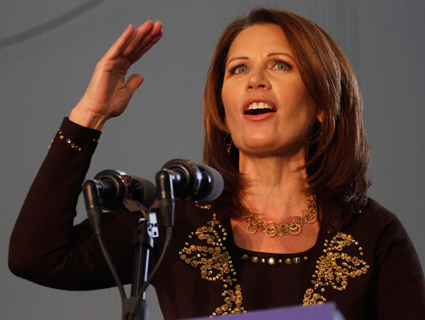

Gage Skidmore/Flickr

Minnesota Rep. Michele Bachmann has a reputation for saying nutty things. Perhaps you’ve heard. To the congresswoman’s critics, her overheated accusations—suggesting, for instance, that President Obama would create “re-education camps” for American kids or that Census data might be used as a tool for mass incarceration—are just the product of mindless conspiracy theorizing.

But that misses the point. There is a method to Bachmann’s madness (such as it is) that her critics don’t always understand. Long before she emerged as a bomb-throwing cable news fixture, Bachmann, who announced on Monday that she’s running for president, cut her teeth in a different sort of campaign that mirrored the religious and constitutional arguments she uses today to attack President Obama’s policies. As a culture warrior working with a nonprofit education watchdog in the Twin Cities suburbs, she laid the foundation for her political career by railing against the Profile of Learning, a state curriculum standard that she and her allies argued was leading the nation toward a pantheistic, pro-abortion, one-world society.

Bachmann’s activism began in 1999, when she ran for a seat on the Stillwater school board. It may have seemed like an unusual move for a parent who home-schooled her children, but Bachmann was unequivocal: the Profile needed to go. Bachmann ultimately lost, but she was just getting started.

Shortly after the election, Mary Cecconi, a school board member who survived the anti-Profile challengers, traveled to a local church to see her opponent, joined by a self-styled education policy specialist named Michael Chapman, give a presentation on the Profile. The duo was traveling the state to discuss the ideology and constitutionality (or lack thereof, in their view) of the curriculum standards on behalf of the Maple River Education Coalition (MREC), one of a handful of groups of concerned parents and educators that popped up to battle the Profile.

“There were a lot of people calling out amens, and a tremendous amount of kind of a visceral love pouring out for her,” Cecconi recalls. “Chapman was supposed to be the headliner but there was no question that she was the star.”

The pair’s critique of the system, as outlined in a fact-sheet they drafted for the MREC two years later, revolved around a fear that federal education policy (of which the Profile was an extension) was stealthily laying the groundwork for a “state-planned economy.” The Profile, which was initially created by former Republican Gov. Arne Carlson, established 10 basic “learning areas” that students were required to pass—things like reading, writing, and mathematics. But according to Bachmann and Chapman, this was merely a gateway; they argued that public schools, in collaboration with business interests, would then funnel children to specific careers through a program called School to Work. Officials in Washington, in that dystopian scenario, would form “workforce boards” to promote different sectors of the economy—green jobs, say—depending on their political whims.

“Government is implementing policies that will lead to poverty, not prosperity, by adopting the failed ideas of a state planned and managed economy similar to that of the former Soviet Union,” Bachmann and Chapman wrote. “The system is based upon a utilitarian worldview that measures human value only in terms of productive capability for the ‘best interests of the state.'”

“She had this very Brave New World kind of thing: ‘This is the federal government programming our kids,'” says Steve Kelley, a former Democratic state senator and gubernatorial candidate who served with Bachmann on the senate education committee.

The warnings about Big Brother irked even some Bachmann allies. “I attended one of their sessions recently in Edina in which a few people commented that the presenters seemed to use ‘scare tactics’ in their presentation,” one supporter wrote in a comment on the group’s website. “While I know that is not their intent in presenting the facts of the [School to Work] and Profile of Learning systems, I, too, felt the same discomfort… I would just encourage them to cut out even more of the details in future presentations in order to eliminate the sense of panic, emotion, and conspiracy that was felt at this session.”

For MREC’s members, fears of a state-planned economy were just the tip of the conspiracy. According to the group, the federal standards were actually part of a globalist plot. As they explained, the Profile was an extension of a Clinton-era program called Goals 2000, which made a preliminary attempt at a basic set of national curriculum standards. That initiative, meanwhile, marked the continuation of an effort endorsed by George H.W. Bush, called “Education for All,” which, in turn, adopted principles originally floated by the United Nations. “Promoting World Citizenship over National Sovereignty is now Official US government policy,” Chapman later wrote.

American Exceptionalism and Judeo-Christian principles, long a Bachmann sticking point, were being pushed to the back burner while environmentalist concepts like “sustainable development” emerged as a tool of the global agenda. Just what would this UN-based curriculum look like? The MREC identified 17 key planks of the global agenda—among them “pantheism,” “evolution,” “socialized medicine,” “one-world government,” and the “creation of ‘biosphere reserves.'” Even International Baccalaureate, the worldwide advanced placement system, drew the group’s scorn; a fact-sheet provided by MREC called it “the foundation of tyranny.”

Among the Evangelical Christians who formed Bachmann’s Minnesota base, the threat of global government is loaded with religious connotations. In the best-selling End Times series Left Behind, the Antichrist—in the form of a smooth-talking United Nations Secretary General—unites the world in a one-world state following the Rapture. Among many Evangelical Christians, globalism is a force for evil. (Bachmann has previously attended conferences devoted to Biblical prophecy and credits Beverly LaHaye, the wife of the Left Behind co-creator, with inspiring her to enter politics.)

One MREC supporter told Minnesota Public Radio in 1999 that the curriculum standard “fits very well with what the word of God tells us is happening, for we are living in the last days, and there will be a one-world government.” (He was not speaking for the group.)

Karen Effrem, a long-time board member of MREC, emphasizes that the group was not religious in nature, however. “Nothing that Maple River did was dealing with End Times anything or with religious discussions,” she says. It was, according to her, purely a constitutional question: Who should determine the content of local curricula?

Ultimately, through the efforts of Bachmann and her allies, the Profile was repealed. After facing fierce pressure from social conservatives during the state GOP’s nominating convention, Gov. Tim Pawlenty appointed an education commissioner who quickly set about developing a new set of standards, and invited MREC members to participate. The process was a mess; during one meeting, a committee member struck a reference to sharing in the kindergarten curriculum because she considered it too “socialist.” After a fierce backlash, the state senate ultimately chose not to confirm Pawlenty’s education commissioner, Cheri Yecke.

Bachmann’s relationship with Maple River was for the most part mutually beneficial. She lent her energy and considerable rhetorical gifts to the cause; the group, meanwhile, provided an entry point into the social conservative grassroots networks that would launch her into office. In interviews at the time, she attributed her surprising success at the polls to groups like MREC.

When the group, which by that point had rebranded itself as EdWatch and begun to expand its reach into other states, held its national convention in 2004, the charismatic state senator was a natural choice to deliver the keynote address. This time, the focus wasn’t on encroaching United Nations tyranny; it was on a threat of a different sort. In a 45-minute speech, Bachmann tackled the specter of the gay agenda in public schools. She alleged that teachers were indoctrinating students in homosexuality and encouraging children to give it a try. Even the word itself—”gay”—was an issue. “It’s part of Satan, I think, to say that this is ‘gay,'” she warned. “It’s anything but ‘gay.'”

Even Pawlenty, then the state’s Republican governor and currently one of Bachmann’s top rivals for the 2012 nomination, wasn’t immune to the group’s scathing criticism: “Under Governor Pawlenty’s supervision, his administration is actively promoting the indoctrination of students into a homosexual worldview and value system,” it warned in an open letter in 2006.

When Bachmann went to Washington, DC, she took Maple River/EdWatch with her. Julie Quist, a former MREC board member, went on to take a job as Bachmann’s district director; Renee Doyle, the former school board member who founded the organization, currently works in the congresswoman’s Washington office. The group closed up shop last December, but Effrem simultaneously launched a new organization, Education Liberty Watch, whose mission is more or less the same.

Bachmann’s war on the Profile of Learning is nearly a decade old at this point, but laid a foundation for her approach to politics that continues today. Her subsequent campaigns against “One World currency” and sustainable development (famously fretting that progressive policymakers wanted all Americans to live in urban “tenements“) reflect a latent and long-standing fear of globalism that stretches at least as far back as the debate over the standards. It’s the product of a coherent, if controversial worldview that’s been honed by her years as a grassroots activist. (Bachmann did not respond to an interview request.)

“The Michele Bachmann you see today is exactly the Michele Bachmann I met 12 years ago; she has not changed one iota,” says her former school board rival Cecconi. “Consistency is her middle name. That’s the quality that people read in her from the back of the room.”