Yuri Arcors/<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=yelling&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=1297687&src=a60f56733e79cb4108036b1548633a0a-6-36">ShutterStock</a>

Over the past week I’ve written a few posts expressing support for the Obama administration’s decision to require health care plans to cover contraception, as well as for its decision to permit only a very narrow exemption for religious organizations. I haven’t really laid out the whole case, though, and today I want to do that in telegraphic form. Then I want to tell you the real reason that my reaction to this has been stronger than you might have guessed it would be, especially considering that this isn’t a subject I wade into frequently. But that won’t come until the end of the post. First, the bullet point warm-up:

- In any case like this, you have to look at two separate issues: (1) How important is the secular public purpose of the policy? And (2) how deeply held is the religious objection to it?

- On the first issue, I’d say that the public purpose here is pretty strong. Health care in general is very clearly a matter of broad public concern; treating women’s health care on a level playing field with men’s is, today, a deep and widely-accepted principle; and contraception is quite clearly critical to women’s health. Making it widely and easily available is a legitimate issue of public policy.

- On the second issue, I simply don’t believe that the religious objection here is nearly as strong as critics are making it out to be. As I’ve mentioned before, even the vast majority of Catholics don’t believe that contraception is immoral. Only the formal church hierarchy does. What’s more, as my colleague Nick Baumann points out, federal regulations have required religious hospitals and universities to offer health care plans that cover contraception for over a decade. (The fact that some such employers don’t cover birth control is mostly the result of lax enforcement.) It’s true that the Obama regulation tightens this requirement, but only modestly: it covers organizations with fewer than 15 employees and it bans copays. Dozens of states already have similar rules on the books. So when Kirsten Powers says, “One thing we can be sure of: the Catholic Church will shut down before it violates its faith,” that’s just wrong. They’ve been working under similar rules for a long time without turning it into Armageddon.

- Some matters of conscience are worth respecting and some aren’t. If, say, Catholic doctrine forbade white doctors from treating black patients, nobody would be defending them. The principle of racial nondiscrimination is simply too important to American culture and we’d insist that the church respect this. I think the same is true today of the principle of nondiscrimination against women, as well as the principle that women should have control of their own reproduction. Like racial discrimination laws, churches that operate major institutions in the public square have to respect this whether they like it or not.

- This new policy doesn’t apply to churches themselves or their devotional arms. It applies only to nominally religious enterprises like hospitals and universities that serve secular purposes, take taxpayer dollars, employ thousands of non-Catholic women, and are already required to obey a wide variety of secular regulations. At organizations like these, the money that pays for employee health care doesn’t come from the church, it comes out of the income stream they get from their customers and clients.

- What’s more, this is hardly a unique matter of conscience. Anyone who pays taxes, including Catholic bishops, ends up financially supporting things they disapprove of. Public regulations often involve financial commitments too, and this one is no different. It’s also pretty minuscule. This is an issue that’s very clearly being blown up for partisan political reasons far beyond its actual impact on religious organizations or religious conscience.

Now, having said all that, it’s also true that I’m normally fairly sympathetic to granting religious exemptions to public policy. You can make a case—not a great one, but a case—that allowing an exemption to the new contraceptive policy wouldn’t actually work a huge hardship on the women affected. And the Catholic Church’s objection to contraception, wrongheaded though I think it is, is plainly of long standing. This is no made-up issue.

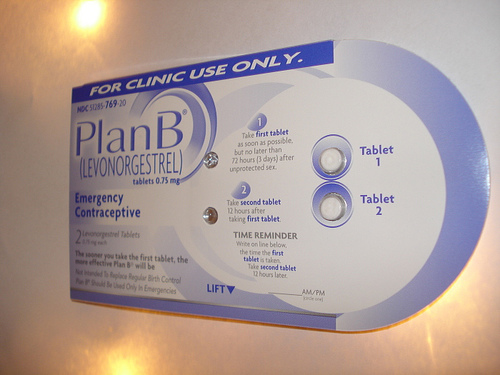

So why am I really feeling so hard-nosed about this? The answer goes back a few years, to the controversy over pharmacists who refused to fill prescriptions for the morning-after pill. I was appalled: If you’re a pharmacist, then you fill people’s prescriptions. That’s the job, full stop. If you object to filling prescriptions, then you need to find another occupation.

But of course, the entire right-wing outrage machine went into high gear over this. And it was at that point that my position shifted: if this was the direction things were going, then it was obvious that there would be no end to religious exemption arguments. The whole affair was, I thought, way over the top, and yet it got the the full-throated support of virtually every conservative pundit and talking head anyway. This was, in plain terms, simply a war on contraception.

So I changed my mind. Instead of believing as a default that we should take religious exemptions seriously and put the burden of proof on the rest of us to explain why they shouldn’t be allowed, I now believe that neutral public policy comes first and the burden of proof should be on churches to provide convincing arguments that (a) An important matter of conscience is being violated, and (b) The public policy in question isn’t important enough to be applied across the board. On the matter of contraception, I don’t think they’ve made a convincing case for either one.