On the night of March 23, 2011, four political operatives arrived for dinner at Scarpetta, a posh Italian restaurant in Beverly Hills’ Golden Triangle. They wore DC power suits but ditched the ties—their one concession to LA fashion. For a bunch of hacks more at ease on Capitol Hill than Rodeo Drive, they blended in well enough. Bill Burton and Sean Sweeney had spent their adult lives climbing the rungs of Democratic politics, including a stint together in the Obama White House; pundit and consultant Paul Begala had advised Bill Clinton in the 1990s; Geoff Garin had been a top pollster for some 30 years. A hostess led them through the Mediterranean-themed dining room, all dark woods and tan walls lit by golden glass lamps, then up a flight of stairs to a private room. Awaiting them was the man they hoped would be their bell cow.

That was the term Begala, the Texas-raised funnyman of the group, used to describe a megadonor who leads his rich friends to bankroll a candidate or cause. Their dining companion, Jeffrey Katzenberg, the CEO of DreamWorks Animation, raised millions for the Obama campaign in 2008, and the fate of their project—and, potentially, the presidency—hinged on convincing him to raise millions more in 2012. They wanted him to take the lead in funding a new super-PAC to support president Obama’s reelection.

Burton, Sweeney, Begala, and Garin didn’t like super-PACs, which can raise and spend unlimited amounts. Nor did the president, who had ripped them as a “threat to our democracy.” Nor did Katzenberg, who felt that the 2010 Citizens United decision was a huge blunder. And yet here he was, listening to a pitch that Begala had rehearsed on the flight to LA. It was hard to think of a presidential election, Begala said, with more at stake. With the economy on the mend, health care reform on the books but not yet enacted, the wars in the Middle East winding down…

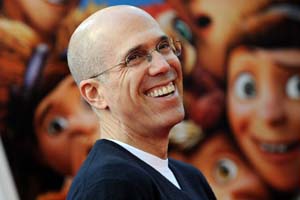

“I know all that,” Katzenberg interrupted. “Tell me your business plan.” At 60, Katzenberg, who stands 5-foot-5, cut a lean and fit figure (“On background, he’s incredibly buff,” says a friend of his), his clean-shaven face taut and tanned, with a disarming, horsey smile. What remained of his graying hair was trimmed to a fine stubble. He wore a V-neck sweater over a T-shirt, slacks, and sneakers—his Hollywood CEO uniform—and he grilled the four operatives with the same intensity he would a potential business partner. What was their fundraising target, and how would they reach it? How would they spend their money—on broadcast, cable TV, online? Who would be their research director? Their ad maker? How much would they pay themselves? What was their strategy?

The answer to that last one was simple: Destroy Mitt Romney. The Republican primaries were nearly a year away, but the four politicos believed that Romney would end up the nominee, so they would focus on him and ignore the rest of the field. They would attack him using the same approach employed by Swift Boat Veterans for Truth and other groups in 2004. “Just as the conservatives took away Kerry’s war record,” Begala said, “we’re going to take away Romney’s strongest asset: his business record.”

Katzenberg, who is worth an estimated $800 million, liked what he heard. By the end of dinner, he pledged $2 million to the super-PAC, later named Priorities USA Action, and promised more money down the road—no strings attached. He also offered to tap his network of wealthy friends and colleagues. And he picked up the tab.

Begala had found his bell cow. “It was the most important meeting of the entire campaign,” he told me recently. “If you tell people, ‘Jeffrey’s behind this, Jeffrey’s helping us,’ man, that really helps.”

Katzenberg’s investment paid off big for Obama. Priorities zeroed in on Romney’s time at the private equity firm Bain Capital, cutting a series of ads depicting him as a real-life C. Montgomery Burns. In one, a union worker recounted how he was ordered to build a stage at his Indiana paper factory; days later, Bain executives strode across it to announce they were closing the plant and firing everyone. It was rated the most effective ad of the campaign; as Republican message maker Frank Luntz would say, “That ad alone has killed Mitt Romney in Ohio.”

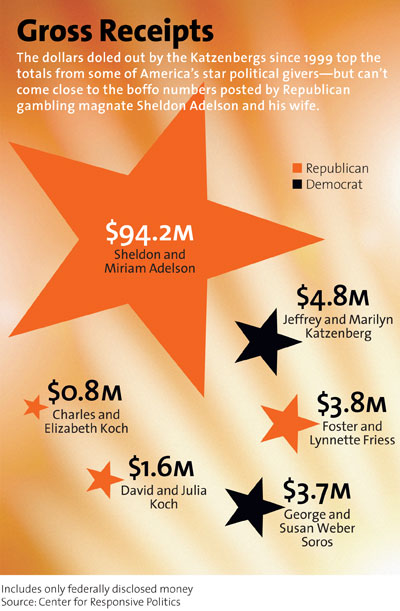

Katzenberg gave $3.15 million to Democratic super-PACs during the 2012 cycle—almost 30 times more than his total reported giving in 2008. (There’s no telling how much he might have given to other groups that don’t disclose their donors.) He steered millions more to Priorities—his friend and business partner, Steven Spielberg, gave $1 million, for instance. He hosted numerous fundraisers for Obama and raised more for the president than anyone else in California. All told, Katzenberg gave or raised more than $30 million to reelect Obama, helping Hollywood make up for Wall Street’s plummeting financial support of the president. And that’s not counting the funds he marshaled for other Democrats, such as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and California Gov. Jerry Brown.

“It’s hard to think of any other donor going back to the [1990s] or even further who did what he did,” says Bill Allison of the Sunlight Foundation. “He’s like soy sauce in Chinese food: He’s everywhere.”

The deep-pocketed kingmaker is a recurring character in American politics. William McKinley might have lost the 1896 presidential election without businessman Mark Hanna, the former US senator and master fundraiser. Harry S. Truman won his first Senate race, in 1934, thanks largely to “Boss Tom” Pendergast, the ruthless Missouri power broker later thrown in prison for tax evasion. Today, conservatives love to demonize George Soros, the liberal financier who gave a record $24 million to elect John Kerry in 2004. But Soros, a longtime supporter of campaign finance reform, didn’t raise a dime for Obama in 2012 and didn’t give to the Priorities super-PAC until very late in the campaign. Katzenberg, who shuns sleep, guzzles Diet Coke, and says his parents “didn’t raise me to sit on the sidelines,” gave early and often. “No one in the United States did what Katzenberg did,” a fellow Obama fundraiser says. “He is in a class of one.”

Jim Messina, Obama’s campaign manager, hails Katzenberg for his role in reelecting the president: “He’s one of the best, if not the best, fundraisers out there.”

If the Katzenberg story has a prequel, it is the story of Lew Wasserman, the canny, irascible, and ruthless mogul who in the 1950s and ’60s transformed the Music Corporation of America (MCA) from a middling talent agency into a mighty studio. Wasserman, a lifelong Democrat, saw the advantages to having friends in power, so he built Hollywood’s first real political machine, a network of performers, business partners, and studio bosses who gave generously to his handpicked candidates. By the 1990s, he was one of the Democratic Party’s all-time biggest donors. Wasserman and his wife, Edie, spoke of US presidents like they were cousins—Jack and Jimmy and Ronnie and Bill; once Wasserman slept in the White House when he couldn’t find a DC hotel room. And when he saw a headline that read something like, “Lew Wasserman Controls Hollywood. Does He Control Washington Too?” he offhandedly said, “Of course I do.”

Wasserman withdrew from politics in the late ’90s, leaving a gaping hole in the Democrats’ fundraising machine. The entertainment industry still rallied behind Al Gore in 2000 and Kerry in 2004. But the marquee donors of that period—movie producer Steve Bing, Power Rangers creator Haim Saban—couldn’t get Hollywood to fall in line like Wasserman could. After a ban on unlimited, undisclosed donations to parties—so-called soft money—went into effect following the 2002 campaign, showbiz donations to Democrats fell off. (The industry’s Republican giving, paltry as it was, held steady.)

Then came Citizens United, dismantling limits on political giving and paving the way for super-PACs—and a new kind of kingmaker arose. So, in 2012 megadonors like Katzenberg and casino tycoon Sheldon Adelson demonstrated just how far some 1-percenters were willing to open their wallets. “There’s now a whole range of opportunities for donors that didn’t exist before Citizens United,” says Bill Allison. And that’s not even accounting for the fact that the Supreme Court could lift what restrictions remain on individual giving, allowing donors to give millions directly to campaigns and parties.

Katzenberg is savvy about which candidates he backs and when he gives, often cutting checks before other donors who are wary of placing the wrong bet. He relishes the nitty-gritty of politics—he’s the rare contributor willing to spend hours on the phone pitching rich people when others would rather stab themselves in the eye. “I don’t know anyone—anyone—in Hollywood that says, ‘Give me a donor list,'” says Donna Bojarsky, a political and philanthropic adviser in Los Angeles. “Except Jeffrey.” And he’s not bashful: “Jeffrey has no problem asking you for, like, way too much money,” Will Smith quipped at an Oscars ceremony honoring Katzenberg.

Obama officials say they respect Katzenberg not only for his fundraising, but also because he has no specific “ask”—no ambassadorship to Switzerland, no regulatory tweak, no nights in the Lincoln Bedroom. Even so, being Hollywood’s liaison to Washington has its perks: Obama takes Katzenberg’s calls, and he and his political adviser, Andy Spahn, visited the White House almost 50 times between them during Obama’s first term. (Not all of Spahn’s visits had to do with Katzenberg.) It has also left him well positioned to advocate for his industry’s and his company’s interests in China’s booming film market.

Katzenberg and Adelson have cast themselves as leading men in a new campaign finance picture, where small groups of wealthy donors wield even greater power, cutting monster checks that reshape the parties’ primaries. “It’ll be wealthy people getting together and picking horses and riding those horses through a primary process and maybe upending the consensus of the party,” says a Democratic strategist. “We’re in a whole new world.”

Adds Paul Begala: “Every Democrat who has presidential ambitions is now going to beat a path straight for Jeffrey’s door. Or they’re too dumb to be president.”

Katzenberg has made a president before. On February 10, 2007, Obama announced his first presidential bid. Ten days later, some 600 guests crowded into a ballroom at the Beverly Hills Hilton for the first major fundraiser of Obama’s campaign, including Tom Hanks, Denzel Washington, Eddie Murphy, and the studio chiefs from Universal, Paramount, Disney, and 20th Century Fox. At one point, Obama adviser David Axelrod wound up standing behind Jennifer Aniston. “I probably lost my ability to fix my place in time as a result,” he recalls. Later that evening, a handful of donors who’d raised $46,000 each gathered at the home of DreamWorks cofounder David Geffen for an intimate dinner with the Obamas.

Obama was the star of the show, but the night’s other breakout was Katzenberg, who, with Geffen and Spielberg, had had the political savvy to bet on the young senator. Katzenberg and Spahn had hoped to raise a half million dollars that night; as the demand for tickets soared, they doubled their target. The final haul was $1.3 million, an eye-popping sum that infuriated Hillary Clinton and her campaign aides, who had believed that Spielberg, Katzenberg, and Geffen—SKG in showbiz parlance and former Bill Clinton donors all—would choose her. Clinton’s campaign even demanded Obama return Geffen’s $2,300 donation after the mogul bad-mouthed Hillary to the New York Times‘ Maureen Dowd. Unfazed, Obama went on to raise $25 million in the early months of 2007, proving he could compete with Clinton in the so-called money primary.

For decades, Katzenberg had been a reliable, if less recognized, Democratic donor. Now, he had stepped onto center stage, signaling to Hollywood’s donor class which way SKG was leaning. “What put Barack Obama on the map was that first-quarter fundraising total,” says Rufus Gifford, the campaign’s head fundraiser. “The February event was a huge part of that.”

Katzenberg’s personality was central to the event’s success. He knows how to navigate Hollywood’s minefield of egos, eschewing mass emails to potential donors in favor of personal calls—which few can refuse. Those who give receive a handwritten thank-you note. Meanwhile, Spahn, his consigliere, counts among his friends Axelrod and former White House chief of staff William Daley (Spahn calls him “Billy”); Spahn and Rahm Emanuel, another ex-Obama chief of staff, appeared in each other’s weddings. “There are a lot of people Jeffrey can get to that political candidates or their campaigns can’t,” says John Emerson, a Los Angeles banker who co-chaired Obama’s Southern California fundraising team. Other industry players “assume that he’s researched the candidates, knows the issues, and there’s a level of due diligence.”

Katzenberg is a political operative’s dream, with little interest in attention for himself—through Spahn, he declined multiple requests to be interviewed for this story—and no ideological litmus tests. He didn’t complain when Obama the lofty-minded candidate gave way to Obama the pragmatic politician. And even as the Priorities super-PAC struggled to get traction, and at least one donor called Katzenberg to try to convince him the project was a waste of money, he stuck with it.

A few days after Katzenberg’s $2 million donation showed up in Priorities USA Action’s monthly disclosure records, a New York Times editorial scolded the group for “abandoning the high ground” and choosing to “raise millions of their own secret dollars.” The Times singled out Katzenberg by name.

Begala shuddered as he read it at his suburban Maryland home. He knew big donors hated seeing their name in print, let alone in the Sunday Times. Katzenberg was the CEO of a publicly traded company, with a reputation to worry about. What if the piece scared away their bell cow? He had to call Katzenberg and do damage control.

Begala stepped outside. If the call got nasty, he didn’t want the kids to hear.

“Did you see the editorial?” he asked.

“What editorial?” Katzenberg said.

“The one in the Times.”

“Oh yeah, I read it last night.”

And?

“That kind of thing doesn’t bother me.”

Begala felt both stunned and relieved. “He’s the first donor I’ve ever met who could shake off a really tough editorial in the Sunday New York Times,” he later told me.

Katzenberg had been called a lot worse.

Before he was Jeffrey—never Jeff—he was Squirt. The son of a Wall Street stockbroker and an artist, Katzenberg grew up on Park Avenue and attended the prestigious Ethical Culture Fieldston prep school in the Bronx’s leafy Riverdale enclave. In the summer of 1965, having been kicked out of the exclusive Camp Kennebec in Maine for gambling with M&M’s, he volunteered on Rep. John Lindsay‘s mayoral campaign. A charismatic, blond, blue-eyed, patrician Upper East Sider, Lindsay was a rare breed even in his own time, a liberal Republican who opposed the Vietnam War and marched in civil rights protests. Katzenberg was 14 when he joined Lindsay’s campaign but looked 12, thus the nickname. “If you needed six cups of coffee at three in the morning, Squirt could get them,” Lindsay said years later.

Katzenberg lured his Fieldston classmates to the campaign office with free pizza and soda, then enlisted them to stuff envelopes. When Lindsay became mayor, Katzenberg started showing up at City Hall after school, sitting in on meetings, quizzing staffers. “Nobody quite knew what his role was,” says Sid Davidoff, a former Lindsay aide and friend of Katzenberg’s. But he devoured politics, proving to be a quick study and tenacious worker. “It was always, ‘What’s the next thing we gotta do?'”

After graduation, Katzenberg dropped out of college to work at City Hall. Dick Aurelio, a Lindsay campaign manager who also served as a deputy mayor, remembers him as an eager, loyal aide fascinated by campaign strategy, ad rates, and the inner workings of politics. One day in April 1970, Aurelio got a phone call while dining at a downtown steak house. His daughter, Jodi, who was being treated at Mount Sinai Hospital after a riding accident, had slipped into a coma. He needed to get to the hospital right away. “Before I know it,” Aurelio says, “I was in Jeffrey’s car and he had a siren—I don’t know where he got it from—that he was holding to the top of his car with one hand and he was driving with the other.” They raced uptown, picked up Aurelio’s wife, and ran every red light. Otherwise, “I would have never seen her before she died,” Aurelio told me.

Davidoff enlisted Katzenberg as his deputy, and when a window got smashed at a volunteer office, or when Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies staged an anti-war protest in the middle of Second Avenue, Davidoff and Katzenberg were dispatched to deal with it. On calmer nights, they took in midnight screenings of cartoons and B movies at a seedy theater on 42nd Street, sitting among the junkies and loners up in the balcony, until their pagers beckoned them back to City Hall. “He always loved the animated stuff,” Davidoff recalls.

On Lindsay’s 1969 reelection campaign, Katzenberg served as an advance man, carrying a suitcase with as much as $100,000 in campaign cash. In 1972, when Lindsay became a Democrat and sought the party’s presidential nomination, Katzenberg signed on; after the ill-fated campaign, he bounced between gigs as a professional poker player and a maître d’.

Aside from politics, Katzenberg nurtured a love of arts and movies, often chattering away about some new record or a pop art show between hands at Aurelio and Davidoff’s weekly poker game. His mentors connected him with the producer David V. Picker, who was looking for a new gofer. Katzenberg jumped at the chance.

After a year with Picker, he moved to Paramount Pictures to work under chairman Barry Diller. Despite his youth and inexperience, he gave as good as he got. The first time Diller chewed him out, as the Hollywood Reporter‘s Kim Masters wrote in her book on Michael Eisner, The Keys to the Kingdom, Katzenberg, then 26, stormed into Diller’s office, slammed his hands on the desk, and said, “This is the first time and the last time that you will ever talk to me that way while I work for you. If you do not want me here, I will leave. If you ever do this again, either start with ‘You’re fired’ or end with ‘You’re fired.'”

Encounters like that, combined with a manic work ethic, served Katzenberg well as the brash, go-anywhere-do-anything lieutenant to Diller and Paramount CEO Michael Eisner. He moved to Los Angeles in 1977, and eventually rose to head of production at Paramount. New York magazine called him Paramount’s “golden retriever.” One colleague said, “The problem with working with Jeffrey is there’s no job too low he won’t do himself.”

Eisner had grown up a block or two away from Katzenberg, and the two sons of Park Avenue privilege forged one of the industry’s most formidable partnerships when they took over the ailing Walt Disney Company in 1984. Eisner, a failed playwright, was seen as the controlling, creative half, and Katzenberg as the workhorse. The stories of Katzenberg’s aggressive management style spread fast in Hollywood—the 6 a.m. meetings, the 200 daily phone calls, the back-to-back-to-back business breakfasts, the prodigious amounts of Diet Coke. Eisner put him in charge of Disney’s film studio, including its stale animation company, and Katzenberg poured everything into the task. He wore the same outfit again and again, and kept a new Ford Mustang on blocks so that when the one he was driving died he wouldn’t have to think about buying a new one.

His motto was “If you don’t come to work on Saturdays, don’t bother to come in on Sunday.” Yet he let his employees take risks, too. “He’d say, ’80 percent of the time you’ll make the right decision, and 20 percent of the time you won’t, but we’ll figure it out,'” a former colleague recalls. With Katzenberg and Eisner at the helm, Disney underwent a renaissance, churning out box office hits like Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Aladdin, The Little Mermaid, and Beauty and the Beast. Disney bagged dozens of awards, and, under Katzenberg, became the industry’s most profitable studio, raking in $800 million in 1994—four hundred times what it had earned a decade before.

On the lot, Katzenberg could be charismatic in one meeting and imperious in the next. The animators bristled at his micromanagement and copious production notes. In his biography of Steve Jobs, Walter Isaacson quotes Katzenberg telling a roomful of artists: “Everybody thinks I’m a tyrant. I am a tyrant. But I’m usually right.”

Katzenberg has mellowed a bit since his time at Disney, friends and former colleagues say. He once said that while working for Eisner he saw himself as a “mercenary soldier. Someone else wrote the music, and I marched to their tune. And if someone poked me in the chest, I would hit them with a baseball bat. And if they hit me with a bat, I would blast them with a bazooka.”

Eventually, Katzenberg would turn that bazooka on his boss. After Disney CEO Frank Wells died in a 1994 helicopter crash, Katzenberg believed Eisner had promised him the job. Eisner disagreed. A few months after Wells’ death, Eisner summoned Katzenberg to his office and handed him a draft resignation announcement. “I was disappointed, sad, angry, scared, philosophical, sad, vengeful, relieved, and sad,” Katzenberg would say years later. He eventually sued Eisner and Disney, seeking $250 million in unpaid bonuses. Katzenberg settled out of court for a sizable sum believed to be close to his initial demand.

On October 12, 1994, flanked by Spielberg and his longtime friend and mentor Geffen (“my dream team,” he called them), Katzenberg unveiled DreamWorks SKG, Hollywood’s first major new studio in 60 years. It would churn out live-action movies, animated films, music, video games, and more. “There’s an opportunity for us to have a revolution,” Katzenberg said. The threesome raised an unprecedented $2.7 billion for their launch and went on to produce American Beauty, Saving Private Ryan, and Gladiator, all Oscar winners. And yet DreamWorks was never able to match the heft of a Warner Bros. or a Universal. In 2004, its wildly successful animation studio, riding high after Shrek, was spun off into a publicly traded company; Katzenberg went with it as CEO. Paramount Pictures snapped up the rest of DreamWorks for $1.6 billion.

SKG may have failed to create the next great studio, but in political circles, their brand grew stronger. During the DreamWorks years, all three men reliably donated to Democratic candidates. While Katzenberg was close enough to President Clinton to host him at his homes in Malibu and Park City, Utah, he was overshadowed by Geffen in the SKG triumvirate. It was Geffen who rallied Hollywood donors and gave $20 million of his own to Clinton and the Democrats; he was rewarded with sleepovers in the Lincoln Bedroom.

On October 18, 2006, Oprah Winfrey interviewed the young Sen. Obama on her show. Afterward, Katzenberg’s wife, Marilyn, told Jeffrey she wanted to meet this rising Democratic star. Spahn, who first introduced Obama to LA’s donors when he was a state legislator running for the Senate, had no trouble setting up the meeting, and Katzenberg, too, was taken. He was reminded of one of his earliest mentors: John Lindsay was “very much about hope and about engagement and change,” Katzenberg says in a public-television documentary on Lindsay released in 2010. “All the things we hear today were things he represented in 1965.” Obama, in turn, was impressed with his new acquaintance, and sought Katzenberg’s support as he mulled a bid for the White House.

Years later, in the final weeks of the 2012 campaign, Obama came to Los Angeles and hailed the couple during a $25,000-a-plate fundraiser, a rare, heartfelt shout-out from a president not known for his warm relationship with donors. “Jeffrey and Marilyn Katzenberg have been tireless and stalwart and have never wavered through good times and bad since my first presidential race, back when a lot of people still couldn’t pronounce my name,” he said. “I will always be grateful to them.”

When David Geffen hosted fundraisers for Clinton, he did not fuss over seating arrangements. But Katzenberg does. In the spring of last year, as he was planning a major Obama event at George Clooney’s house, he told the campaign that he wanted something grander than the usual pep-talk-plus-photo-op. He wanted Obama to hang out, to mingle. Each table would have 10 donors and 11 chairs; Obama or a top aide would sit in the spare one and chat, before moving on to another table. The campaign was reluctant to sign off on a night of political speed dating, but Katzenberg insisted.

He and Spahn also suggested raffling off tickets to a couple of low-dollar donors, raising an extra $7 million before the first guest arrived. The night of the event, Obama worked a crowd—Salma Hayek, Jack Black, Barbra Streisand—cheered by his announcement the day before of his support for gay marriage. Katzenberg milled around, leaning on his friends to open their checkbooks. The total haul: $15 million, making it one of the most lucrative fundraisers in history. “I’ve been around this business for a long time, and I’ve never seen anything like that,” says Dick Harpootlian, a longtime Democratic operative who earned a ticket.

Obama aides say they sought out Katzenberg and Spahn for guidance on messaging and outreach to wealthy Democratic donors at every turn. Rufus Gifford, Obama’s 2008 and 2012 campaign fundraising chief, says, “I knew that from the moment I took this job I would call Jeffrey for advice: What should I do? How would I go about doing it? They were a couple of our greatest allies.” Jim Messina, Obama’s campaign manager, says he was talking to Katzenberg as early as 2010 about how to make the reelection the most technologically adept campaign in American history.

Katzenberg has said he wants nothing, personally or professionally, in exchange for his support of the president, and DreamWorks’ DC agenda is hard to glean: The studio has no lobbyists and is not part of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). Yet it is hard to deny that he—along with Hollywood as a whole—has benefited from his connections. In the 2012 fiscal-cliff fight, for instance, the White House insisted Congress preserve a $430 million tax break for film studios that keep production jobs in the United States. But nowhere are the benefits to Katzenberg clearer than in his company’s efforts in China.

The industry’s expansion into China’s $2.7 billion film market, which is expected to supplant the United States’ as the world’s largest in 5 to 10 years, hasn’t been without obstacles. Several studios, including DreamWorks, are under federal investigation for potentially violating US anti-bribery laws in China. And until recently, the Chinese government would allow only 20 foreign films to screen in its theaters each year, and kept a greater cut of ticket sales than Hollywood thought was fair. In 2009, the United States won a World Trade Organization ruling urging China to open up, but to no avail.

In July 2011, ahead of a trade visit to China, Vice President Joe Biden met with industry leaders who asked him to press their case. Biden, too, returned empty-handed. Seven months later, Xi Jinping, then China’s leader-in-waiting, made his first official visit to America. On hand to greet him was Katzenberg, who scored a seat next to Xi at a State Department luncheon.

Later that week, Xi and Biden traveled to Los Angeles, and Katzenberg joined them for lunch with Gov. Brown. Biden spent the day pushing Xi on the film quota and profit sharing disputes. The White House wanted to bump the studios’ portion from 13 percent to 27 percent, but as the negotiations intensified, Biden asked Katzenberg and Disney CEO Bob Iger what they could live with. Then Biden made Xi a new offer: 25 percent. Xi agreed, and he also said China would let in 14 more foreign-made 3-D and IMAX movies each year.

Katzenberg was simultaneously working on a $350 million deal to open Oriental DreamWorks, a new animation studio in Shanghai—and it couldn’t happen without Xi’s approval. That same day, at a US-China economic forum held at a downtown LA hotel, Katzenberg officially unveiled the project—and proudly announced that it now bore Xi’s personal endorsement. “It’s hard to overestimate how big a deal this is for DreamWorks Animation,” he told the Financial Times.

Spahn insists Katzenberg had no discussions with “anyone in the Obama administration” about the Shanghai project, and denies he had any role in the WTO resolution. But those wins did more than show the perks of having friends in high places; they put Katzenberg’s deal-making savvy on full display. At the end of Xi’s visit, all parties walked away as winners: The White House rushed out a press release celebrating the WTO agreement as a “breakthrough” in trade relations. Xi got a Hollywood ending to his trip. And the entertainment industry—including DreamWorks Animation, which has invested heavily in 3-D—won more access to a booming film market.

Even when show business is on the losing side, Katzenberg knows how to work the angles. In January 2012, Chris Dodd, the powerful former senator who’d recently taken charge of the MPAA, was feverishly working to get the Stop Online Piracy Act passed as a safeguard against illegal downloading. Silicon Valley and the netroots saw SOPA as an attempt to muzzle free speech online, and Dodd began hearing rumors that Obama would also oppose the bill. So he asked Katzenberg to get a firm read of Obama’s thinking, and to urge the president not to dismiss SOPA. “It was kind of mortifying for the MPAA” to rely on Katzenberg, Masters says—especially given that DreamWorks isn’t in the association.

Ultimately, even though Katzenberg wanted SOPA as much as the other studio heads, he declined Dodd’s request. But he knew that any White House opposition to SOPA could do real harm to Obama’s relationship with Hollywood—there was even talk of boycotting the president’s fundraisers. So a few days after the White House finally came out against the bill, Katzenberg called Obama and suggested he and his top aides reach out to the studio chiefs to soothe their egos and shore up their support. Barry Meyer, the CEO of Warner Brothers, received one of those calls; he and his wife went on to raise more than $500,000 for Obama’s reelection campaign. In the end, Katzenberg chose to help Obama win over his industry rather than helping his industry win over Obama.

For people in fundraising, the campaign cycle never stops. Days after Romney lost, 2016 Republican hopefuls including Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal and Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell courted Adelson, the casino mogul, during a trip to Las Vegas.

Political adviser Donna Bojarsky says an already common question in Democratic fundraising circles is “Who is SKG going to support?” Katzenberg and Spahn are set to cohost a big fundraiser for Newark Mayor Cory Booker’s 2014 Senate bid; they also met with Messina about Organizing for Action, the nonprofit group aiming to raise $50 million to advance the president’s second-term legislative agenda. Spahn told me he and Katzenberg have heard from many 2014 House and Senate hopefuls looking for Hollywood money. Katzenberg has even been active in Los Angeles, raising more than $150,000 to elect Wendy Greuel, a former DreamWorks employee running for mayor. “This is a very long effort for [Katzenberg], a lifelong effort,” Paul Begala says. “My sense is this is not just about one election.”

He would know. On November 6, 2012, Begala was at CNN’s Washington bureau, readying for a long night of parsing election results, when his cellphone buzzed. It was Katzenberg. The network had just called the election for Obama.

The two men traded congratulations. Katzenberg thanked Begala for the work he and the Priorities team had done. Then he asked, “So what’s next on the agenda? What comes next?”

“Jeffrey,” Begala answered, “I haven’t even gotten time to get drunk yet.”