Donna Winkler

The sun was beating down on Rockdale, Texas, when Donna Winkler arrived at her sister’s ranch-style, clapboard house on the afternoon of July 29, 2013. Winkler was concerned about Sherill. At the age of 54, she had lost her job as a school bus driver after falling and injuring her wrist. Her husband, Clemon Small, a former crack addict, only worked a few days a week as a karaoke DJ. Recently, the Smalls had moved from nearby Austin to Rockdale, population 5,400, to cut costs.

Winkler knew her sister helped support herself by fostering children for Texas Mentor, a private agency that finds homes for children who have been removed from their parents’ custody. She had taken in an infant and a two-year-old girl named Alexandria Hill. Texas Mentor paid the Smalls $44.30 a day to care for both kids. The company earned $34.74 daily on top of that to monitor the Smalls. Winkler thought Sherill was in it for the money.

That July day, Winkler walked into the living room to find Alexandria standing, facing the wall, in a dark room everyone called the man cave. With blond hair and blue eyes, Alexandria stood 32 inches tall and weighed just 30 pounds. She liked kitties and the color purple. Alexandria turned around and smiled at Winkler.

“Hi, Alex,” Winkler said.

“No, you turn around,” Sherill Small barked at the girl.

A squat woman with stringy brown hair and a prominent mole on her cheek, Small seemed on edge. She told Winkler that Alexandria had been getting in trouble all day. Among her offenses: waking up before Small and taking some food and water from the kitchen.

Winkler stayed at Small’s house for two hours that afternoon. Two-year-old Alexandria stood in timeout in that dark room the whole time, she said.

At about a quarter to seven that evening, Clemon Small woke from a nap and left for a meeting at a nearby restaurant, leaving Sherill alone with Alexandria and the infant. About 15 minutes later, Sherill dialed his number, then 911.

First at the scene was Ward Roddam, the chief of the Rockdale Volunteer Fire Department, who was so surprised to find no one in the front yard waving him down that he called dispatch to make sure he had the right address. Inside, he encountered what he would describe as one of the strangest scenes in his 25-year career: Alexandria’s limp body lay on the floor while Clemon sat on the couch and Sherill talked to 911. Roddam found mucus on Alexandria’s mouth, suggesting that CPR, which foster parents are trained to administer, had never been attempted.

On the witness stand 15 months later, Roddam was asked if the Smalls seemed panicked. “‘Panic’ does not describe it at all,” he said. They seemed “very calm.”

What happened in Rockdale that night would be the subject of a weeklong trial in the fall of 2014, focusing on the care of Alexandria. But it also opened a window into the vast and opaque world of private foster care agencies—for-profit companies and nonprofit organizations that are increasingly taking on the role of monitoring the nation’s most vulnerable children. The agency involved in Small’s case was the Lone Star branch of the Mentor Network, a $1.2 billion company headquartered in Boston that specializes in finding caretakers, or “mentors,” for a range of populations, from adults with brain injuries to foster children. With 4,000 children in its care in 14 states, Mentor is one of the largest players in the business of private foster care, a fragmented industry of mostly local and regional providers that collect hundreds of millions in tax dollars annually while receiving little scrutiny from government authorities.

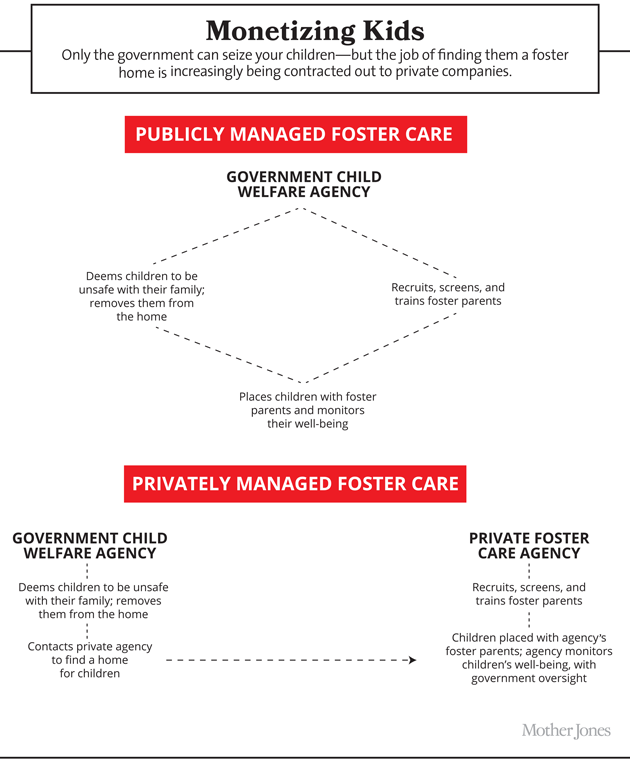

Squeezed by high caseloads and tight budgets, state and local child welfare agencies are increasingly leaving the task of recruiting, screening, training, and monitoring foster parents to these private agencies. In many places, this arrangement has created a troubling reality in which the government can seize your children, but then outsource the duty of keeping them safe—and duck responsibility when something goes wrong.

Nationally, no one tracks how many children are in private foster homes, or how these homes perform compared to those vetted directly by the government. As part of an 18-month investigation, I asked every state whether it at least knew how many children in its foster system had been placed in privately screened homes. Very few could tell me. For the eight states that did, the total came to at least 72,000 children in 2011. Not one of the states had a statistically valid dataset comparing costs, or rates of abuse or neglect, in privately versus publicly vetted homes.

“It’s troubling,” says Christina Riehl, senior staff attorney for the Children’s Advocacy Institute at the University of San Diego School of Law. “There are so many places where the government puts money to fix a problem without adequately checking to see if the money is actually fixing the problem.” Good data would make the system more accountable, Riehl says, but “data is a low priority because it’s difficult. How do you measure child safety?”

Mentor and other private foster care agencies say they are committed to children’s well-being, and that nothing can prevent the occasional tragic incident. But in my investigation, I found evidence of widespread problems in the industry—failed monitoring, missed warning signs, and, in some cases, horrific abuse. In Los Angeles, a two-year-old girl was beaten to death by her foster mother, who was cleared by a private agency despite a criminal record and seven prior child abuse and neglect complaints filed against her. In Albuquerque, New Mexico, prosecutors alleged that foster parents screened by a private agency beat their foster son so badly that he suffered brain damage and went blind. (A grand jury refused to return an indictment in the case.)

In Chattanooga, Tennessee, a foster father vetted by a private agency induced his 16-year-old foster daughter to have sex with him and a neighbor. In Riverview, Florida, a 10-year-old girl with autism drowned in a pond behind a foster home. The private agency that inspected the home had previously identified the pond as a safety hazard but had not required a fence. In Duluth, Minnesota, a private agency failed to discover that a foster mother’s adult son had moved back into her home. The son, who had a criminal record for burglary that would have disqualified him from being around foster children, went on to sexually abuse a 10-year-old foster girl. In Texas, at least nine children living in private agency homes died of abuse or neglect between 2011 and 2013.

Roland Zullo, a researcher at the University of Michigan who has studied foster care privatization, believes tragedies like these may be linked to the financial incentives of the industry, which he says are not aligned with child welfare. “This is just the kind of service where the market approach doesn’t work,” he says.

The bottom line for private foster care agencies—whether large, for-profit corporations or small, local nonprofits—is tied to the number of foster parents on their roster, and thus their ability to place children quickly. Given that every foster parent represents potential revenue, Zullo says, an agency may be more likely to overlook sketchy personal histories or potential safety hazards. There’s little incentive, he adds, to seek out reasons to reject a family, to investigate problems after children are placed, or to do anything else that could result in a child leaving the agency’s program. And as tough as the margins are for nonprofit agencies, the perverse incentives are exacerbated at for-profit agencies that need to make money for owners or shareholders.

“What happens,” Zullo says, “is the lives of these children become commodities.”

Alexandria’s grandmother, Diann Hill, has graying hair and a world-weary way about her. Over plates of fried catfish and okra at a diner in Lexington, Texas, she told me how her granddaughter ended up in foster care.

It was November 2012, three months after Alexandria and her parents—Diann’s son, Joshua Hill, and his girlfriend, Mary Sweeney—moved from Florida to Austin to be closer to Joshua’s family. Mary and Joshua, both in their early 20s, had problems. Mary suffered from grand mal seizures that prevented her from being alone with Alexandria. Joshua, who according to state records had served time behind bars as a juvenile, struggled with anger issues. They argued over their daughter. They smoked pot. Child protection got involved after receiving a couple of calls about Mary and Joshua, including a report that Joshua nearly dropped Alexandria down a flight of stairs (an incident Joshua denies). “Mary and Josh weren’t perfect,” Diann said. “They popped dirty for marijuana. No other drugs. Just marijuana. It’s not like they were getting Alex high, smoking in front of her. They waited until she went to bed; she was safe in the crib. They didn’t leave her alone in the house. She was never sick a day in her life. They fought. What couple doesn’t fight?”

In early November, Joshua told child protection he was going to move, with Alexandria, into his parents’ home near Lexington, a plan the agency approved. But he didn’t follow through; he and Mary remained in Austin while Alexandria lived with his parents. The state didn’t like this arrangement, in part because Joshua’s dad had been convicted in the 1990s for having sex with Diann’s then-16-year-old daughter from a previous relationship. (Diann says she called the police on him and divorced him while he was serving time, but later remarried him.)

In late November 2012, a state investigator signed an affidavit requesting foster care for Alexandria, citing “serious safety concerns” about Mary and Joshua’s “limited parenting skills.” Alexandria was placed with a foster family. But Joshua complained about the girl’s care in January 2013, according to Diann, and she was transferred to Sherill and Clemon Small.

By this time, there had already been warning signs about Sherill’s capability as a foster parent. She’d reported to the company that she was stressed out by fostering children, something that might have set off alarms for someone familiar with her background.

She had told her Mentor screener that she had been a foster child herself, entering the system at age two, when her mother could no longer provide for her and six siblings, and that her experiences had been “good and bad.” Once, a foster parent made her sit outside in the dark on a cold Missouri night for punishment.

Mentor’s assessment also revealed that Sherill didn’t raise one of her three daughters, Jennie Langley. Instead, the assessment said that Jennie was raised by her paternal grandmother and that Sherill had a “despondent” relationship with her daughter. The Mentor screener explained this by noting that Jennie was a defiant child who as an adult didn’t approve of Sherill marrying a black man. The assessment says that Mentor officials spoke with Sherill’s other daughters but gives no indication that Jennie or her grandparents were ever contacted. (Mentor later said it tried to contact Jennie, but was unsuccessful.)

I tracked down Jennie Langley in rural southeastern Texas. Leroy Langley, her grandfather, answered the phone. Leroy said that he and his wife had formally adopted Jennie when she was about seven. In fact, he said, they once had custody of all three of Sherill’s daughters because Sherill was “wild, a street woman.” One of Sherill’s sisters and a daughter confirmed the story to me, saying that the daughters lived with the Langleys for several years in the mid-1980s.

It took me just a few phone calls to get this information. There’s no indication that Mentor went to the same effort.

Americans have been horrified by the foster care system for as long as there’s been foster care—about a century and a half. In the 1850s, the abolitionist Charles Loring Brace founded the Children’s Aid Society of New York, which began removing poor and neglected children from the city and shipping them, by train, to new homes in rural communities. Before long, critics of the “orphan trains” were accusing the society of recklessly placing little thieves and liars into good, upstanding homes. Child protection in general remained in the hands of private charitable organizations for decades, although state legislatures sometimes allocated them money. But in the late 1800s and early 1900s, states began to take the lead, and by the middle of the 20th century, foster care had become entirely a government function.

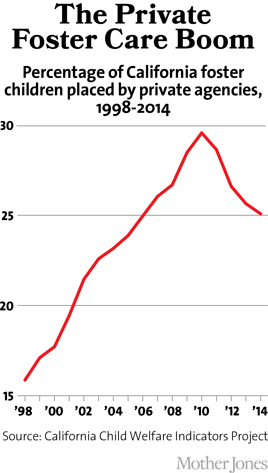

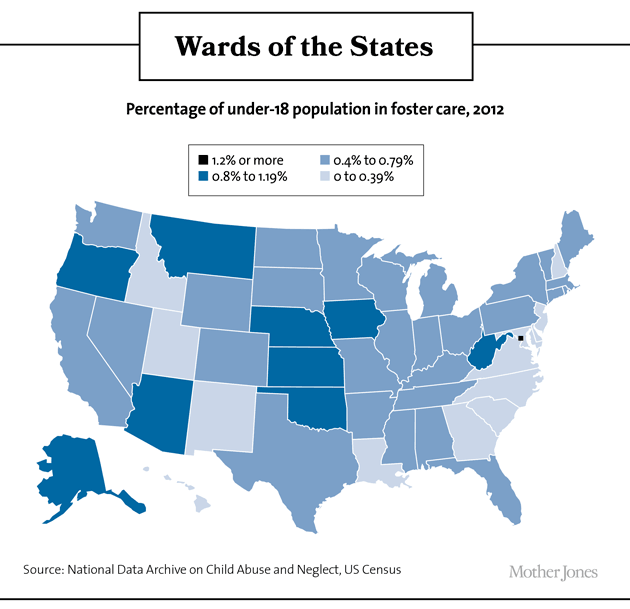

Today, some 250,000 American children enter this struggling system each year, and child welfare agencies are in perpetual need of more foster parents to handle the influx. Against this backdrop, the private sector’s promise of more-efficient services at a lower cost has been hard to resist. A couple of states (Kansas and Florida) are entirely dependent on private foster care agencies. Texas, where 90 percent of foster children are housed in private agency homes, is seeking to privatize the rest of the system—even as child advocates warn that quality of care is slipping. “Texas has chronically underfunded the child protection system,” said Ashley Harris, a former CPS caseworker who now works for the advocacy group Texans Care for Children. “I don’t think we can expand privatization until some of these basic issues are addressed.”

Private foster care agencies generally eschew media scrutiny, but I found one in Sacramento, California, that was willing to give me an inside view. Positive Option Family Services, a small nonprofit with just 15 employees, is based on the east side of town in a strip mall with stained carpets and scuffed walls. I was somewhat surprised that the agency’s CEO, Jody Kovill, let me hang around the office, because Positive Option has a checkered record: Since 2008, two children in its care have died, one of appendicitis and the other in a mysterious house fire. The agency oversees only about 70 children, yet state investigators have found more than 190 deficiencies in its operations since 2009, including several failures to screen the criminal records of adults with access to foster children. In May 2013, the state threatened legal action if the agency didn’t clean up its act (though no charges were brought).

Positive Option staffers frequently grumbled about their treatment at the hands of county regulators. But other than that I found them to be affable, earnest people who seemed genuinely concerned about the welfare of foster children. Every month, Positive Option hosts a two-hour continuing education class for foster parents in a room with crayon-streaked tables and secondhand chairs. I attended several over a period of months, and each time I was struck by the reunionlike atmosphere, where foster parents hugged their hellos and agency social workers were on a friendly, first-name basis with everyone.

Kovill, the cofounder, is an energetic 82-year-old with a white beard who continues to manage the organization on a day-to-day basis. Kovill feels a special kinship with the foster children he serves: He says he was abandoned by his father when he was about seven and given to a shoemaker as a laborer. “Foster care is a good system,” Kovill said. “I wish it had been there when I was a kid.” (Kovill told me he changed his name long ago to break from the family that abandoned him. He wouldn’t tell me what his old name was.)

Kovill told me the margins are tight in private foster care, especially if child welfare is your top priority. He said he once had to sell land he owned in Arizona to keep Positive Option, which has annual revenues of about $1.2 million, afloat. Some of his employees report taking 10 percent pay cuts several years ago for the same reason, cuts that remain in effect today. “I’m still a businessman, and I still try to stay in the black as best I can,” Kovill told me one day in the cramped office he shares with his wife, Luan, who works at the agency for free. “But if it meant a car seat for a baby, if it meant diapers for a baby, if it meant safety for a child, the bottom line is gone.”

Kovill took responsibility for Positive Option’s problems, saying they came about in part because he was distracted by the agency’s financial struggles during the recession. “I just trusted everybody to do what I do—I work hard,” Kovill said, referring to some former employees he eventually fired. “I figured they did too. Well, you can’t do that.”

The state of California pays private foster care agencies like Positive Option a monthly fee for each child in one of their homes. That fee ran from $1,714 to $1,977 (depending on age) per child per month in fiscal year 2013. Under state regulations, roughly half of that money is required to go directly to foster parents, but agencies can elect to give more; Positive Option, for example, rewards outstanding foster parents with more money. Whatever is left over after paying the foster parents goes to the agencies—up to $968 per child per month. In 2013, California paid a total of $308 million to private foster care agencies.

Joshua Hill says he knew Alexandria wasn’t going to make it the moment he laid eyes on her in the hospital. She was hooked up to a ventilator, tubes snaking from every part of her body, a brace on her neck. “There’s no way she was going to wake up from that,” he said. “Her eyes were swollen. There was no chance.”

It was Halloween when we met at a park in Lexington, Texas, near where his parents live. As we talked, children roamed the small town’s main streets, trick-or-treating in the late afternoon light. Joshua wore an olive Army T-shirt over camo pants, a backward cap concealing his long hair, his long, wispy goatee bobbing up and down as he spoke. He and Alexandria’s mother had signed a settlement with Mentor, the terms of which he was not allowed to disclose. But the 25-year-old, who made ends meet delivering pizzas for Domino’s when Alexandria was in foster care, pulled up in a late-model Scion tC with a throaty engine and told me he owns property just outside of town.

Joshua said he got the call at around 9:30 p.m., which would have been about two and a half hours after Small dialed 911. “They just said it was something with Alex,” he said. “She had an accident. That’s all they would say.” Joshua was broke, and the hospital was an hour away, but a friend gave him $40 for gas. “I bought a pack of cigarettes and hauled ass,” he said.

Joshua showed little emotion when we talked, until he described seeing his daughter in the hospital. Then his voice dropped and his eyes grew wet. “I asked the doctor flat out: ‘Is there any chance at all that she could wake up even a little bit?’ He said no. There was too much damage inside of her.”

Alexandria was kept on life support until July 31 so her mother’s family could drive in from Florida to say goodbye. After the plug was pulled, a doctor allowed Alexandria’s mother to hold her for 15 minutes before declaring her dead. A subsequent autopsy found the little girl had bruising on her right cheek, left ear, left knee, right ankle, chin, back, and buttocks; multiple blunt-force injuries to her head; subdural hemorrhaging; and two tears in her liver. A third of her blood was found pooled in her abdomen.

Sherill Small was indicted for capital murder—but it was far from a clear-cut case. Small was the only person who really knew what happened, and she claimed it was just a terrible accident.

Foster care caseworkers are expected to intimately know the parents to whom they entrust vulnerable children. A good caseworker will know the stressors in a foster parent’s life and will carefully monitor the home to ensure the parent doesn’t become overburdened. The job requires vigilance and experience, because a missed warning sign can lead to tragedy. “The radar, in my opinion, always needs to be up,” says Sheila Van Vleck, a longtime caseworker who has worked for both private foster care agencies and the government in California. “The stakes are very high.”

When screening foster parents, the obvious danger is missing a criminal conviction or a child abuse charge. But there are many other issues that can interfere with a foster parent’s ability to care for children. In 2006, a two-year-old girl in Victorville, California, drowned in the bathtub when her privately vetted foster mother temporarily forgot about her, according to a lawsuit against the private agency. The lawsuit claimed the foster mother suffered from impaired memory and walked very slowly, using a cane. In another case, in 2008, a private agency in rural California placed a nine-year-old boy with the same family as a 17-year-old foster boy with a history of aggressive actions, inappropriate sexual behavior, and hallucinations. In a lawsuit, the younger boy later claimed that the older boy crept into his bedroom and sexually assaulted him.

Private agencies have also been sanctioned in some cases for failing to educate foster parents on relevant laws or even basic parenting skills. In December 2010, a six-month-old boy was found dead in a crib littered with stuffed animals, clothes, an adult pillow, and an unsecured blanket, according to lawsuits against Los Angeles County and the private agency that vetted the child’s foster mother. The county investigator concluded that the young foster mother didn’t understand safe sleep practices.

Heather Lamie was caring for five young children when her inexperienced caseworker at The Baby Fold, a regional nonprofit foster agency in Illinois, recommended that she take another foster kid. It was December 2010, and the mother of Lamie’s three foster children had just given birth to a fourth. Twenty-seven years old, Lamie also had two children of her own, ages eight and five. Her husband, Joshua, worked overnight shifts an hour away from their home in rural Illinois. Joshua’s schedule effectively made Heather the sole caretaker for the six kids, all eight or younger.

The Lamies’ oldest foster child was four-year-old Kianna Rudesill, a mischievous kid with long black hair who liked SpongeBob and having her nails painted. Kianna and her siblings had been removed from their biological mother, Tawnee Jones; the children’s father, James Rudesill, had tried to obtain custody but says the authorities refused because he had served time for a marijuana offense.

Shortly after receiving her fourth foster child, Heather Lamie started asking The Baby Fold for help. She requested time off from caring for the children and assistance driving them to their many mandated appointments. The Baby Fold maintains it gave Lamie all that she asked for. But state investigators later found that the agency denied her requests, and that it didn’t recognize the growing stress on Lamie.

Lamie also complained that Kianna was having behavioral problems. She told social workers that the little girl was violent with her siblings and routinely injured herself. A therapist observed bruises on Kianna’s face and ear, but she accepted Lamie’s story, even though state investigators now say those injuries are consistent with abuse.

On May 3, 2011, Lamie called 911, reporting that Kianna had had a seizure. At the hospital, she was found to have severe head injuries, bleeding in the brain, and dozens of bruises in various stages of healing all over her body.

More than three years later, Lamie was found guilty of first-degree murder. The prosecutor argued that Lamie snapped under the “overwhelming” pressure of caring for so many young children.

Investigators with the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services found that The Baby Fold provided inadequate monitoring and recommended that the supervisor overseeing the case be disciplined. But the agency refused, saying it was an isolated incident.

Mitchell Frazen, The Baby Fold’s lawyer, told me the agency was duped by a manipulative foster parent. He notes that the state had originally vetted the Lamies and placed the first three foster children with them before handing management of the case over to The Baby Fold. Frazen says his agency bears no blame for Kianna’s death, even though The Baby Fold was responsible for monitoring the home. “It’s not going to come as a blinding revelation that [the state] is trying to cover its own ass,” he said.

Sixteen days after Alexandria Hill was taken off life support, in August 2013, the Mentor Network held an earnings call. Nothing was said about Alexandria’s death, but Bruce Nardella, Mentor’s president, did tell analysts that the company’s foster care business was doing well. “During the last year we have focused intensely on recruiting more Mentor foster parents who can provide caring, nurturing environments for children,” Nardella said, and that had led to increased revenue. Mentor generated $1.2 billion in net revenue in fiscal year 2013, with $218 million coming from its “at risk youth” services, which include foster care.

Around that time, a woman I’ll call Amanda quit Pennsylvania Mentor in disgust. She had previously worked in a women’s prison, where “I saw a lot,” she told me. “Nothing could have prepared me for Pennsylvania Mentor.”

Amanda (who didn’t want her identity revealed for fear of being blackballed from the social-services industry) said she was hired to supervise other Mentor social workers. Early on she observed her new charges conduct foster parent training. The social workers, she told me, were overworked and hadn’t had time to prepare; they read slides from an overhead projector and used decade-old material as foster parents dozed off. (Mentor says it has started rolling out a new training program that is interactive and engaging.)

Amanda said Mentor expected a lot of its social workers—too much, in her opinion. Everyone was working 50 to 60 hours a week, she says. Every night, Amanda said, she’d go home to feed her kids, then get on the computer and work until midnight, only to be back at the office by seven the next morning. “It was such a negative environment because you’re under so much pressure,” she said.

But what bothered Amanda most was Mentor’s focus on the bottom line. One child, she says, set his foster parents’ bedroom on fire. Amanda’s bosses wanted to keep the child in the home. She said she had to fight to get him transferred to an institution where he could be watched more closely. Another time, Amanda said she wanted to get rid of a foster father who wouldn’t follow the agency’s directions with a mentally ill child. She wanted to hold him accountable, but she said her bosses told her: “We need to keep every foster parent we can.” (After this story appeared in print, Buzzfeed’s Aram Roston has also detailed a range of abuses in Mentor foster homes, including a case in which the company continued placing children with a foster family where a child had reported being sexually abused.)

The only time Amanda remembers Mentor reprimanding anyone was when a foster mother took a child to a doctor’s appointment while drunk—and even then, she said, there was a “huge debate” within the company before the mother was dismissed.

After just a few months on the job, Amanda decided she couldn’t take it anymore. “That’s not where my values lie,” she told me.

I found Amanda and several other former Mentor employees on LinkedIn, and a couple of others through court records. Many told similar stories. A woman who worked for Mentor Maryland told me the company repeatedly let foster parents slide if their homes weren’t up to regulations. Several former Mentor employees said supervisors offered $100 bonuses for every new foster parent they could sign up. (Mentor denies this.) “Executives only care about the money and it is all they talk about,” a current Mentor employee wrote in an anonymous April 2014 review of the company on the website Glassdoor.com. In all, 173 current and former employees had posted reviews of Mentor on Glassdoor as of mid-January. Only 29 percent would recommend the company to a friend. (The average recommendation rate on Glassdoor is 58 percent.)

Dwight Robson, a senior executive at the Mentor Network, told me that of course the company is concerned with profits—and that’s exactly what keeps it focused on children’s well-being. “If you don’t do your job, your bottom line is going to be in a lot of trouble,” he said. “And if you do do your job, you’re going to grow and you’re going to have a healthy bottom line.”

But Rachel Wingo, who used to work in Mentor’s office in Hendersonville, North Carolina, says it seemed to her that children were lost in Mentor’s push for profits. “The success of the program is defined by how many heads are in bed at midnight,” the 34-year-old told me. If children were bouncing around from home to home, Mentor supervisors didn’t seem to care, she said, as long as they continued moving from one Mentor home to another. (Mentor says foster children in North Carolina who left its care in fiscal year 2014 changed homes an average of 1.5 times during their time in its program, with an average stay of 7.8 months.)

Wingo, who quit Mentor in the spring of 2013 to work in a bicycle shop, chose her words carefully when we spoke. Mentor has powerful attorneys, she said, and when you leave the company, “you sign things”—nondisclosure agreements. Speaking out, she said, could hinder her future ability to find work in the field. But Wingo said she has no interest in working in private foster care ever again. “The bottom line is a dollar, not a child’s well-being,” she said.

Shameela Keshavjee, who once worked for Mentor in Garland, Texas, and is now in private practice as a licensed marriage and family therapist, also told me she and her colleagues were under constant pressure to keep up the number of heads in beds. “‘We need more kids. We need more placements. We need, we need, we need,'” she said, describing the attitude of her supervisors. “It was all about churning out more numbers.”

Keshavjee recalled a time when Mentor approved a foster mother she and the other case managers didn’t trust. The woman’s only income came from caring for special-needs foster children; she didn’t have a phone and was difficult to reach. “It was borderline unsafe,” Keshavjee said, but Mentor ignored the concerns. (Keshavjee says she’s heard Mentor has since closed the foster home.) “The management was so clearly concerned about keeping the business going they would open homes that the clinical coordinators didn’t believe should be opened,” she said.

Keshavjee said no one at the company ever directly talked about money, but the message was clear nonetheless. “At the end of the day, it felt very profit-driven,” she said.

Approachable Foster Family Agency, a small nonprofit in Merced, California, was a solid business proposition for Franklyn and Cynthia Vincent, the couple who established the agency in 2004. Cynthia’s counseling business contracted with the agency while Approachable also paid both her and Franklyn six-figure salaries. By 2009, the Vincents and Cynthia’s business combined were making half a million dollars from Approachable, more than 10 percent of the nonprofit’s annual revenue.

But in the spring of 2010, Approachable faced a challenge: One of its foster mothers was demanding that the agency find a new home for three difficult children. The Dixon siblings—D.J., age eight; Dexter, four; and Shalea, one—had come from a volatile family that struggled with drug and mental-health issues. Both D.J. and Dexter had developmental disabilities; Shalea had respiratory problems. Approachable stood to lose as much as $2,600 in monthly revenue if it couldn’t find them a new home.

The Vincents turned to Wendy Ford, a 42-year-old mother of eight who was already fostering an additional child through Approachable. The agency had inspected her four-bedroom house in Merced, but Ford told me the review was perfunctory. Several potential safety issues were left unaddressed, including the backyard swimming pool, which did not have a cover, and the fencing around the pool, which had no locks.

Ford says her foster parent certification only permitted her to house three foster children. But, she figured, if Approachable wanted her to take four, it must be okay. On March 31, 2010, the three Dixon kids moved into her home. Dexter made an immediate impression on her. “He had quite a personality,” she told me. “He was just full of life.”

Five days later, Ford’s sister, who was also staying at the home, found Dexter floating facedown in the pool. He’d wandered out of sight for just a few minutes and apparently ridden a plastic toy right into the water.

First responders found Ford performing CPR on Dexter, both of them covered in his pink vomit. Miraculously, the child survived cardiac arrest and multiple organ failure. But he suffered such severe brain damage that he’s not expected to be able to hold an entry-level job as an adult. Now nine years old, Dexter is a shell of his former self. “He has the frown lines of a 50-year-old,” says his mother, Shalea Dixon, who regained custody of her children.

One afternoon last spring I watched Dexter and his little sister play outside in their cul-de-sac. While the little girl zipped about on a scooter, giggling and shouting, Dexter rode his bicycle in slow, careful circles, his face drawn and sad.

Ford, who was charged with felony child abuse for letting the boy wander away, ended up pleading no contest to misdemeanor child endangerment and got three years’ probation. Approachable paid $825,000, without admitting liability, to help settle a civil suit brought on Dexter’s behalf by a court-appointed attorney. (The money is now in a fund set up for his care.) Franklyn Vincent, Approachable’s CEO, declined to comment.

The state, meanwhile, fined Approachable all of $500—not for the near-drowning or the cursory home inspection, but for failing to criminally screen Ford’s sister. Subsequent inspections by the state of California found six Approachable homes that were over capacity and at least three with fencing or pool problems.

Michael Weston, a spokesman for the California Department of Social Services, bristled when I asked why the state didn’t penalize Approachable more. “Can we shut down agencies? Of course we can. But it’s not necessarily always in the best interest of everyone involved.” Why not? “There’s not a huge group of people trying to be foster parents right now, and that’s a challenge—finding enough homes.”

Dwight Robson, the chief public strategy and marketing officer at Mentor, comes from the public sector—before joining the company in 2003, he held several positions in Massachusetts state government and worked on Democratic campaigns, including John Kerry’s Senate reelection bid. He told me that Mentor is a “mission-driven organization,” its goal to help individuals—foster children and adults with disabilities or severe brain injuries—live in residential settings. He stressed that providing quality services to clients was the company’s No. 1 priority, and he noted that in fiscal year 2014 alone, it closed 869 foster homes over concerns about their “fitness” to care for children.

Robson dismissed the complaints of the former employees I spoke with, saying that Mentor employs about 22,000 people nationwide, many of whom have had long tenures with the company. Incidents like the death of Alexandria Hill, he said, are tragic but “extremely rare.”

William Grimm, a senior attorney at the California-based National Center for Youth Law in Oakland, agreed that it’s virtually impossible to prevent the occasional incident. “I don’t think you could have a perfect system,” he said. “Unfortunately, there’s going to be a few people that squeak through.”

Robson told me that Mentor implemented new policies in response to Alexandria’s death, and that Texas Mentor voluntarily stopped taking new foster children until the case could be reviewed by authorities. Robson said Mentor staff “misjudged the character and commitment” of Sherill Small; the company has also admitted to missing that Small had an outstanding warrant for passing a bad check and failing to background-check her daughters, who frequented the home and had criminal recÂords of their own. “Clearly, we didn’t do our job,” Robson said. “That’s a fact, and one that we’re not going to run from.”

I attended Small’s trial last fall, in the high-ceilinged old courthouse in Cameron, Texas. The proceedings were repeatedly interrupted by the piercing sounds of a train whistle from tracks less than a block away. The three male attorneys wore cowboy boots; the one female, pink high heels. Small slumped before a box of tissues, occasionally pushing up her glasses to dab her eyes.

For the jury, Milam County District Attorney Bill Torrey displayed a blown-up photograph of Alexandria, taken just days before the incident. In it, the little girl wears a canary yellow tank top, her pale skin ghostly in contrast to the brown puppy she’s clutching. Alexandria looks into the camera without smiling. “We are here because on July 29, 2013, Sherill Small murdered Alexandria—I’ll call her Alex—Hill,” he intoned.

Over the next week, the jury would learn that Small changed her story about what happened several times, first claiming that the child simply fell, then saying that she was running backward and fell, finally saying that she let go while swinging Alexandria by the arms. Jurors then watched an interrogation video where Small said she had been lying the whole time, that the real story was that she had been swinging the child over her head and accidentally dropped her on the floor. Several medical experts testified that Alexandria’s injuries were inconsistent with that story or any of the other ones, but were indicative of abuse. A police officer and an emergency room doctor also reported that Small didn’t inquire about the girl after she was rushed to the hospital. Witnesses repeatedly said they didn’t see Small cry.

But the most damning testimony for Small—and Mentor—came directly from Small’s family. Small’s sisters testified that Small didn’t seem to like Alexandria. Police photos showed that Alexandria’s room was devoid of toys or decorations, while a room used by Small’s teenage granddaughter was decked out with pictures, a zebra-striped blanket, and a Pikachu doll.

The jury also heard that Small hit one of her own daughters when the girl was just two years old, giving her a black eye and a knot on the head when she fell. Meanwhile, Small’s granddaughter admitted that Sherill and Clemon concealed from Mentor that a family friend, who had not been screened, sometimes stayed in the house. Clemon testified that he didn’t know Mentor’s guidelines on timeouts—no more than one minute for every year of age. Under Mentor’s own rules, Alexandria shouldn’t have been in timeout longer than two minutes. Taken together, the testimony suggested that Mentor didn’t really know the Smalls or what was going on in their home—or, for that matter, what had happened to Sherill herself when she was in foster care.

A psychological assessment painted a grim picture of what Sherill described as a “very sad” childhood. It said she was frequently spanked or put into isolation for things she hadn’t done. It got so bad that in her early teens, Sherill ran away from her foster home to live with a man who repeatedly raped her. Sherill told the psychologist that she preferred living with the man because she was “actually treated better and not beaten or left outside.” Sherill reported feeling depressed most of her life and attempting to kill herself once. She also testified that she had a son whom she gave up for adoption “because I was real young, I didn’t have a place to live, and I wasn’t going to have him live on the street.” Mentor’s background screening never found out about him either.

In early November, the jury found Small guilty of capital murder, sentencing her to life without parole. The verdict was the biggest legal victory in the career of assistant district attorney John Redington, but he told me afterward that the win felt hollow. “We get vengeance on these people and it makes us feel better temporarily,” he said. “But true justice would be making real change in the system so no kid is ever put through this kind of nightmare again.”

This story was supported by UC-Berkeley’s Investigative Reporting Program, where Brian Joseph was a fellow.