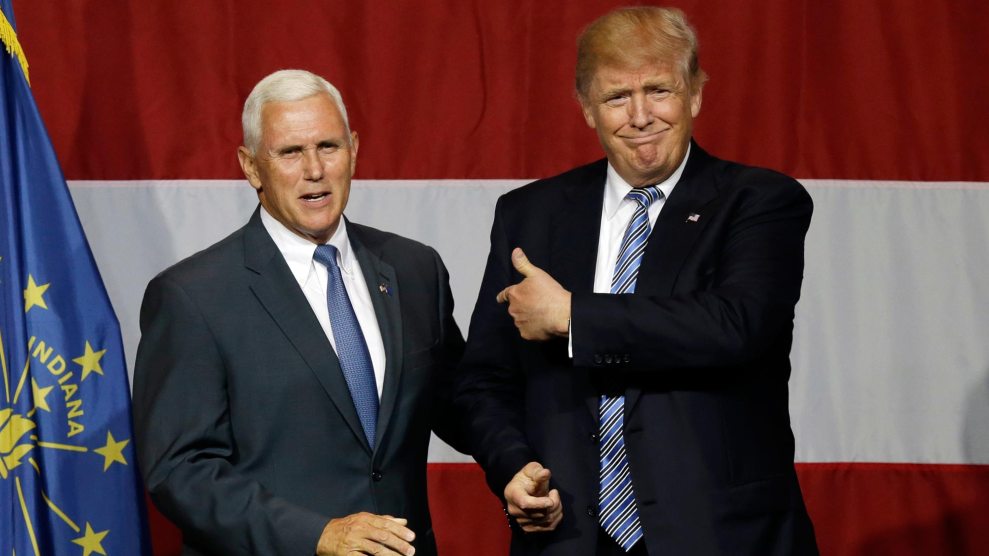

Darron Cummings/AP

Donald Trump has run an exceptionally negative campaign relying on over-the-top personal attacks, crude insults, and rude name-calling—and that could put Mike Pence in an awkward position.

Pence, the Indiana governor who’s reportedly Trump’s pick for vice president, is now expected to become the chief promoter and defender of Trump’s campaign. The second banana on a national ticket traditionally has one paramount mission: to assail the presidential nominee of the other party. But Pence once took a strong and moralistic stand against negative campaigning, vowing that he would no longer engage in personal attacks.

In 1990, Pence ran for Congress in a race that has gone down as one of the nastiest in Indiana history. The Indianapolis Monthly went down memory lane in a 2013 profile of Pence:

One Pence ad featured a man in a tacky robe with a thick Arab accent thanking [his Democratic opponent Phil] Sharp for his support of foreign oil. Some still maintain that the ad starred Pence himself, and its lost footage has become a sort of Ark of the Covenant in Indiana politics.

Pence lost that race and came to regret the campaign he had run. (Pence had lost largely because he had used campaign dollars to pay his mortgage, car payments, credit card bills, and even golf fees. At the time, this was not illegal, but it was bad politics.)

In 1991, Pence penned a candid personal essay about this congressional contest, titled “Confessions of a Negative Campaigner.” The short essay, published in the Indiana Policy Review, began with a quote from the Bible about sin, and Pence stated plainly, “Negative campaigning is wrong.” He wrote:

First, a campaign ought to demonstrate the basic human decency of the candidate,. That means your First Amendment rights end at the tip of your opponent’s nose—even in the matter of political rhetoric.

Pence noted that negative attacks are “wrong” because they distract voters from the important issues. He asserted that following his loss in the 1990 election, he had undergone a “conversion” on the topic of negative campaigning: “A campaign ought to be about the advancement of issues whose success or failure is more significant than that of the candidate.”

So how might Pence apply all of this to Trump’s campaigning—or to the attack-dog role he might be asked to assume on behalf of Trump? It’s fair to say that no major presidential nominee in modern times has so depended on invective and nastiness. Will Pence turn down the assignment to attack Hillary Clinton? If he does join Trump’s ticket, he will go through an un-conversion. Pence will be endorsing and enabling an extreme version of the sort of politics he once disavowed. And down the road, he might have to write yet another confession.

Here is the full text of Pence’s “Confessions of a Negative Campaigner,” which was made available online by reporter Craig Fehrman:

It is a trustworthy statement, deserving of full acceptance, that Christ Jesus came to save sinners, among whom I am foremost of all.

— 1 Timothy 1:15

In the wake of the 1990 election cycle, after one of the most divisive and negative campaigns in Indiana’s modern congressional history, the words of Saint Paul provide an appropriate starting point for the confessions of a negative campaigner.

Negative campaigning is wrong. That is not to say that a negative campaign is an ineffective option in a tough political race. Pollsters will attest—with great conviction—that it is the negatives that move voters. The mantra of a modern political campaign is “drive up the negatives.”

That is the advice political pros give to Republican and Democratic candidates alike, even though negative ads sell better for Democrats. (My admittedly biased explanation is that Republican voters disregard a Democrat’s negative ads as “predictable” while expecting a Republican to be “above that sort of thing.”)

But none of that explains my conversion. It would be ludicrous to argue that negative campaigning is wrong merely because it is “unfair,” or because it works better for one side than the other, or because it breaks some tactical rule.

The wrongness is not of rule violated but of opportunity lost. It is wrong, quite [simply, because*] he or she could have brought critical issues before the citizenry.

And this wrongness is not limited to the personal but extends to the general. Yes, it was personally wrong for me to waste my moment and limited campaign dollars talking about how an opponent might or might not have financed a rural retreat. But in my party’s defeat, as unaddressed issue piled upon unaddressed issue, it seems more grievous that the faithful were left with so few clues as to how I would have governed differently.

Campaigns ought to be about three simple propositions:

First, a campaign ought to demonstrate the basic human decency of the candidate. That means your First Amendment rights end at the tip of your opponent’s nose—even in the matter of political rhetoric.

Second, a campaign ought to be about the advancement of issues whose success or failure is more significant than that of the candidate. Whether on the left or the right, candidates ought to leave a legacy—a foundation of arguments—in favor of policies upon which their successors can build. William Buckley carries with him a purposeful malapropism. “Don’t just do something,” it says, “stand there.”

Third and very much last, campaigns should be about winning. A fellow member of the Failed Politician’s Club told me recently, “Our only mistake was that we thought that winning was the most important thing we could do.” He considers it more than a literal correction that Vince Lombardi’s exact words were, “Winning isn’t everything, but wanting to win is.” (The “winning is everything” line was spoken by the ignoble and now forgotten Red Sanders.)

Negative campaigning is born of that trap. But one day soon the new candidates will step forward, faces as fresh as the morning and hearts as brave as the dawn. This breed will turn away from running “to win” and toward running “to stand.” And its representatives will see the inside of as many offices as their party will nominate them to fill.

—-

[*] I supplied the words in brackets—it seems like a sentence or two disappeared while the essay was being formatted. Hey, it happens! I double-checked with the Review‘s editorial office, and the bracket-less text above is exactly what’s in the print issue.