Flickr/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/nycpublicadvocate/4881884117/">Public Advocate Bill de Blasio</a>

The Supreme Court may have opened the floodgates for corporate campaign spending, but Bill de Blasio, New York City’s public advocate, is doing his part to staunch the unfettered flow of political money—one company at a time.

De Blasio’s strategy is simple enough. Since this spring, he’s been approaching major corporations and lobbying them to publicly pledge that they won’t avail themselves of the free-for-all made possible by the Citizens United decision. The campaign has been surprisingly successful. Due to his efforts, a small but growing roster of corporate heavy hitters has taken vows of campaign-finance austerity.

De Blasio—a former campaign manager for Hillary Clinton’s 2000 Senate race—scored his latest victory last week with JP Morgan, after three months of talks with the company. The Wall Street investment firm said on Friday that it had “no plans to change our political contributions policies as a result of this decision,” which allows corporations to spend unlimited amounts on ads advocating for or against a candidate. JP Morgan didn’t do much to trumpet the decision, simply adding the language to its website. But de Blasio—who as public advocate acts as the city’s watchdog—hopes the company’s decision will motivate other firms to follow suit.

JP Morgan has joined other major firms, including Goldman Sachs, that de Blasio has convinced to maintain the campaign finance status quo. De Blasio has used leverage as a trustee on the New York City’s Employees’ Retirement System, which oversees $30 billion in assets and has invested in the majority of companies that the public advocate’s office has targeted. Using this approach, he’s also helped pressure Microsoft to take the vow, which joined the likes of IBM, Xerox, Colgate-Palmolive and other name-brand companies that previously pledged to abstain from the ruling*. But for every company that signs on, there are a host of others that have declined. These companies—which include Google, Monsanto, and Exxon, among many others—are subjected to a public shaming of sorts, their names listed on the public advocate’s website.

De Blasio maintains that decisions by even a handful of corporations to opt out of Citizens United-enabled spending could make a difference in the 2010 elections. Under the decision, corporations can now buy ads that directly endorse or attack a candidate and give money to independent groups to do the same—a change that de Blasio calls “a clear and present danger,” given their deep pockets.

“One corporation that goes all in could change the course of these elections,” he says in an interview, arguing that the pledges he’s received from a handful of corporate giants have helped blunt the “single worst part of the Citizens United decision.”

De Blasio launched his campaign in May, when Goldman Sachs was already mulling whether to adopt a separate shareholder resolution that would have required greater disclosure of its political spending. Though that resolution ultimately failed, de Blasio took the opportunity to lobby the company to opt out of the new Citizens United-enabled spending. After months of talks, the Wall Street firm—not known for being sympathetic to grassroots causes—made the surprising decision to make the pledge, stating that it would not change its political expenditures as a result of the court ruling. “It was the enlightened thing to do,” de Blasio says, calling the decision an act of corporate social responsibility. “They got praised for doing the right thing—it was very selfless.” Certainly, Goldman Sachs stood to benefit from some positive PR at the time, given its tarnished public image in the wake of the financial crisis.

Since then, de Blasio has lobbied some of the nation’s top corporations—mostly household names that focus on consumer products—to follow suit. So far, nine companies have vowed restraint. He’s also enlisted state officials in New York and Connecticut, as well as Illinois Governor Pat Quinn, to throw their support behind the campaign, as well as partnering with grassroots groups like New York’s Citizen Action.

Campaign finance watchdogs have generally praised the campaign—but they warn that its impact is likely to be more symbolic than substantive. “It’s a noble campaign…but it’s entirely voluntary,” says Craig Holman, a government affairs lobbyist for Public Citizen. “It helps draw attention to the problem, but it isn’t going to actually solve the problem of excessive corporate money flowing into politics.” Holman points out that corporations—even those that agree not to take advantage of Citizens United—could still hide there spending by giving gobs of money to independent groups like the Chamber of Commerce. Nonprofits like the Chamber aren’t required by law to disclose their donors, so there’s no way to hold companies accountable to their promises of restraint.

Ultimately, new campaign finance regulations will probably be the only way to curb the overall impact of Citizens United, which is just the latest federal ruling to lift restrictions on corporate participation in elections. The DISCLOSE Act, for example, would have forced outside groups to reveal corporate contributors to political ads. But the GOP swiftly killed the bill over the summer, arguing that the rules were cumbersome and unfairly restrained the ability of corporations to participate in the political process. While the Democrats are making a last-ditch effort to pass a watered down version of the legislation before the likely Republican takeover of the House, the new rules wouldn’t apply to the 2010 election cycle.

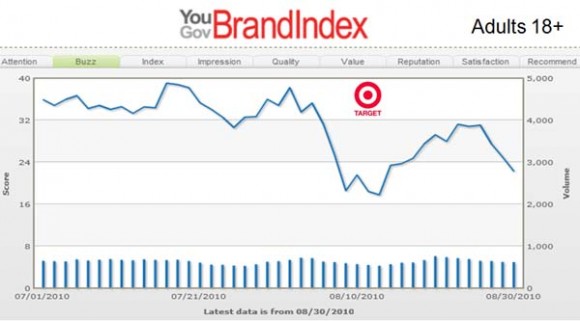

There’s still some hope that even left to their own devices, corporations will at least think twice before exploiting Citizens United—at least in terms of buying campaign ads directly or donating money for 527 “soft money” groups to advocate for or against a particular candidate. Target and Best Buy experienced significant blowback for supporting Republican gubernatorial candidate Tom Emmer, particularly given their LGBT-friendly reputations (and the candidate’s decidedly unfriendly position on gay rights). While spending across the board has reached record levels, there have been few other major companies that have been as brazen in trying to use the new post-Citizens United rules to their advantage.

Companies that ramp up their political spending could also get roped into what de Blasio calls a “spending arms race,” in which competing advocacy groups and candidates may start flocking to them to solicit their money and support. Amidst the Target controversy, for example, even progressive groups that oppose the Citizens United decision in principle pressed the company to counter its support for Emmer by donating $150,000 to pro-gay candidates. Target didn’t end up making such amends, but de Blasio warns that companies will still be subject to this kind of lobbying: “Your corporate treasury becomes everyone else’s piggy bank.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that de Blasio had lobbied all of these firms to sign onto the pledge. Some of them had implemented these policies prior to his campaign.