A meteorologist monitors weather patterns at NOAA Boulder.Hyoung Chang/Getty

After spending two years in confirmation purgatory, Barry Myers, the Trump nominee to head the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), asked the White House last week to rescind his nomination. Myers explained that he needed to step down because of recent cancer surgery and chemotherapy, but his nomination has been stunted by controversy from the start. Now the 11,000-employee agency, which is part of the US Department of Commerce and charged with tracking the weather and collecting scientific data on the nation’s coastlines, will face its third year without a permanent director.

Former NOAA senior official Andrew Rosenberg, who now directs the the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, says this means that the agency could remain paralyzed, its employees made wary by the fact that the interim head, atmospheric scientist Neil Jacobs, could be gone without warning. “NOAA people do their jobs really carefully and with great passion,” Rosenberg says. “But you want to know you have the backing of the agency to really deeply engage in your work. That becomes more difficult when you don’t have someone with the authority.” Especially after two years grappling with the troubling possibility of a Myers confirmation.

The head of NOAA has never been a particularly contentious presidential appointment—the two preceding directors were voted in by unanimous consent in the Senate—but Myers was a notable exception. Before his nomination by President Donald Trump, Myers was CEO of AccuWeather, a company that sells weather forecasting technology—much of which is sourced from NOAA’s raw data. The Washington Post reported that AccuWeather has consistently peddled climate denialism since at least the mid-1990s, when it worked with the fossil fuel–backed Global Climate Coalition. While CEO, Myers heavily lobbied to privatize NOAA’s data, largely to ensure his own venture could remain competitive in the face of NOAA’s free and easily accessible data. His lobbying raised initial concerns about his ability to run the government agency without injecting policies that would benefit the weather forecasting industry.

Though he stepped down from AccuWeather to receive the NOAA nomination, Myers’ brother, Joel, took over as its chief executive, a tenure that has been characterized by continuing the company’s established position that climate change does not exist. As recently as this summer, Joel Myers called into question humankind’s role in changes to the planet’s temperature and weather conditions. “[T]here is no evidence so far that extreme heat waves are becoming more common because of climate change,” Myers wrote in an essay published on the AccuWeather website last August. “Especially when you consider how many heat waves occurred historically compared to recent history.”

The climate denialism espoused by the Myers brothers is directly opposed to the work of NOAA, which is responsible for managing the National Weather Service and using its network of satellites to forecast the effects of climate change. NOAA was one of the agencies involved in the fourth National Climate Assessment, a 1,656-page comprehensive assessment of how the effects of climate change—shrinking coastlines, extreme weather, and more damaging wildfires—are reshaping the US. Even in the face of a presidency that disputes the realities of global warming, NOAA has attempted to assert that, yes, climate change is real.

Then there was the additional problem of Barry Myers’ tenure at AccuWeather, which occurred during a time when the organization was rife with allegations of sexual misconduct, as reported by Mother Jones and substantiated by Department of Labor documents earlier this year:

The Washington Post obtained a US Department of Labor report that found “widespread sexual harassment” at AccuWeather under Myers’ leadership, which further worried current and former NOAA employees, as well as other scientists. They remembered that in 2016, Congress passed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Sexual Harassment and Assault Prevention Act, after several of the agency’s employees had come forward complaining about the situation there. They were aware that Myers was the head of AccuWeather when an investigation conducted by the Department of Labor’s Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs found that “AccuWeather was aware of the sexual harassment but took no action to correct the unlawful activity”…

For many employees, the combination of the history of sexual harassment at NOAA, the lack of support for Myers, and then the problems at AccuWeather when he was in charge, made his nomination even more concerning.

The Washington Times reported that in his letter requesting to withdraw his nomination, Myers complained that Democrats contested his nomination since 2017 “for no reason other than my support for the administration.” But former NOAA administrators are more likely to suggest Myers’ many conflicts of interests and the work culture he oversaw were the reasons his nomination was stalled for such a long time before being withdrawn. “Any one of these major problems should have disqualified him from leading NOAA,” says Jane Lubchenco, the NOAA administrator from 2009 to 2013. “Together [they] clearly gave many senators ample reason to oppose his confirmation.”

For NOAA, which is staffed largely by scientists and engineers, Myers’ withdrawal means they will be spared his potential conflicts of interest, management shortcomings, and complicity with the Trump administration’s refusal to take climate change seriously. But with only an acting director, it will have to continue in a “holding pattern,” says Rosenberg, who was a deputy director of NOAA’s fisheries department during the Clinton years. “He was just not the right guy for the job,” Rosenberrg explains. “I think NOAA people were quite concerned.”

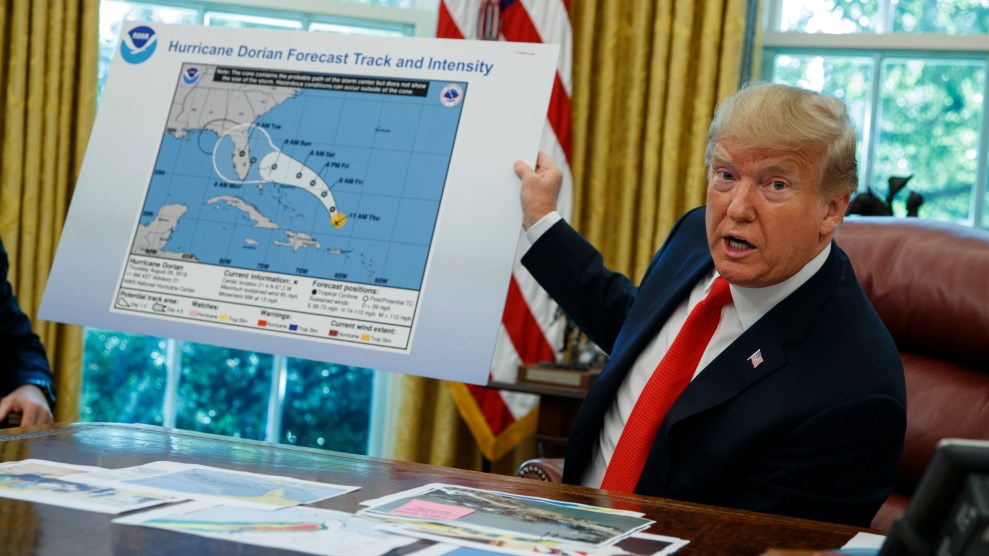

Jacobs, who has been the acting head of NOAA since February, has done an “adequate job,” Lubchenco says, especially when considering the fact that the president stands in the way of much of NOAA’s defining characteristics—scientific integrity, nonpartisanship, and transparency. But Jacobs’ performance hasn’t been without controversy. In September, when NOAA was tracking Hurricane Dorian’s path, it noted that Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Georgia were in the Category 5 storm’s path. With a sharpie in hand, Trump incorrectly claimed that Hurricane Dorian’s trajectory would cut across Alabama, a prediction with no evidence and one that conflicted with NOAA’s findings. After White House pressure following the agency’s announcement of the correct path, NOAA was forced to realign its view with the president’s, before then returning to its original data-driven findings. Though NOAA ultimately stood by its findings, but then its leadership took flak for allowing extreme weather to become political fodder. “Dr. Jacobs failed in this defining moment of his career,” Lubchenco says. “To his credit, he has apologized to his colleagues, but the damage was done.”

Now that the possibility of a Myers-headed NOAA is no more, the question remains of who—if anyone—will be in line. With its record number of positions filled by “acting” directors, the administration has a poor track record for confirming leadership. Rosenberg says he hasn’t heard any rumblings about another replacement. His prediction? “Jacobs will remain in place, certainly in the near term, and possibly through the end of the administration.” That means that for the first time since it was established by Richard Nixon in 1970, NOAA may spend an entire presidential term without a confirmed head. The future of NOAA’s leadership is unclear, but with Myers out of the running, the agency has avoided a political storm that would be far more damaging than the one created by a president drawing on a map with a Sharpie.