President Trump speaks during a news conference about the coronavirus on March 14.Alex Brandon/AP

Among the many crises caused by the global coronavirus pandemic is a crisis of information. Good information, as Charlie Warzel wrote in the New York Times, is one of our best defenses against the virus. But faulty science, untrustworthy authorities, and intentional attempts to deceive all serve to worsen the disaster—and can be a matter of life and death.

The recent confusion about CDC guidance on wearing face masks shows exactly how vital—and how difficult—public health communication can be during a pandemic. To get an understanding of how it’s done right, I spoke to Dr. Dean Schillinger, a medical doctor and professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who studies how public health literacy can affect patient outcomes. As the nation’s leaders grapple with how to communicate medical information effectively, we wanted an expert’s opinion on how to turn messaging into mobilization. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

The coronavirus messaging regarding masks has been confusing, to say the least. At first, it was: “Don’t wear masks; save PPE for healthcare professionals and people on the front lines.” Now it’s evolved to a recommendation to wear a cloth mask, even though efficacy studies aren’t yet definitive. How could that messaging have gone better?

Certainly, the messaging was botched in that it’s been confusing. As a public health person, when you’re facing an epidemic and you don’t know which way it’s going to go, you always have to err on being conservative. So it would have been a right call to say: “We’re recommending masks, even though we don’t have evidence that [this virus] works like the flu. We don’t know anything about it. It seems to be going rampant in China. We’re going with the mask thing. And yes, we know it’s weird. Yes, we know there’s stigma, but we’ve talked to a bunch of people—here’s our message.” That would have been a fine outcome.

But now that we have a new consensus, the most important question is: What is the communication plan around masks? We now have a different recommendation; let’s do it right. And I think we’re seeing an example of how it’s not being done right. Everything from Trump’s undermining of the message at his press conference to the absence of amplifiers and key celebrities modeling how cool it is to wear a mask. Everything that’s supposed to happen is not happening. How many people understand that you need to wear a mask not to protect yourself but to protect others? Is that important to convey? And how do we overcome the stigma that is perhaps associated with wearing a mask? How do you make a mask?

I mean, there are loads of communication questions and cultural questions that no one’s asking. It’s easy to say, “Wear a mask.” But that doesn’t get the job done.

So what does get the job done? What makes for effective public health communication?

So there are a few points:

1. Have a plan: That plan should be rooted in what we call a “logic model,” where you clearly define what the messages and messengers are trying to achieve. All those things need to be mapped out, and the strategy needs to be aligned with those objectives.

One of the problems we’re seeing here in the current crisis is the absence of a coordinated communications plan. Particularly at the federal level, it’s been quite apparent that nobody really knows who’s in charge of communication. So that, in part, is why we’re so enamored by the daily presentations given by Gov. Gavin Newsom in California and Gov. Andrew Cuomo in New York, because we see someone who’s presenting communication in a way that feels logical.

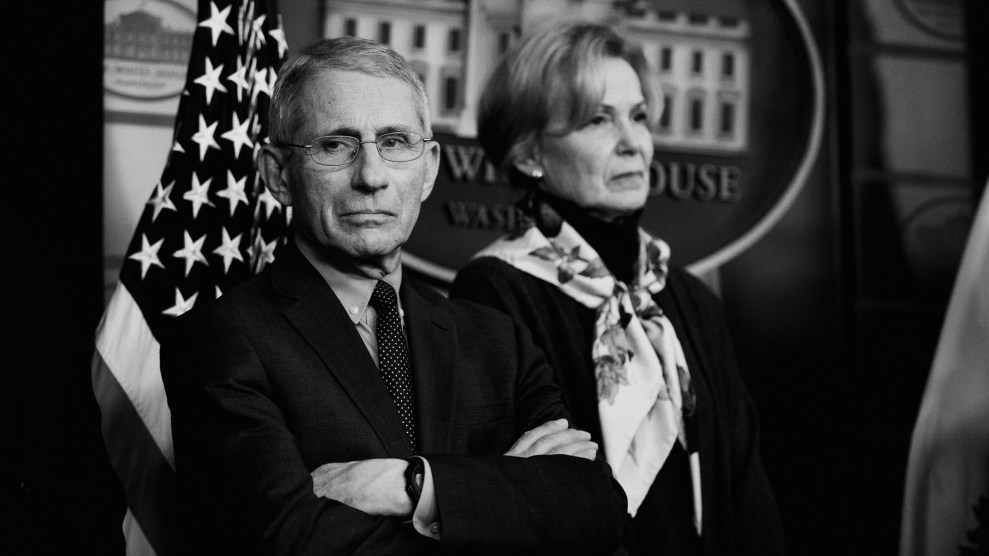

2. Get the right people: Next is having the appropriate person deliver the message. People who have both gravitas and have engendered enough trust in the general population that they will tune in and have a higher likelihood of adhering to any recommendations. That person should be closely aligned with other trusted individuals from diverse communities who can amplify and tailor the message.

So a great example of this is when Tony Fauci and Steph Curry had their Instagram conversation. People who follow Steph Curry who might not be following Dr. Fauci suddenly hear Dr. Fauci and immediately trust him because Steph Curry is showing him respect. So having a network of influencers and amplifiers for the communicator in chief, I think, is very, very important because we live in an extremely diverse country.

3. Don’t be overconfident: It’s important to be clear about what we know and what we don’t know. One of the problems that we have seen both from the formal and informal communication sector is overconfidence in statements made when, quite honestly, this is a brand new beast. And I think sometimes communicators—particularly at high levels—feel the need to present a level of certainty and make recommendations based on a belief that they are certain. That strategy may provide short-term gains, but may undermine trust in the long term.

We have to acknowledge, for example, that we’re not entirely sure if you have to be symptomatic to transmit the disease, that we don’t know if asymptomatic people can transmit the disease yet. And I think if that kind of conversation had happened, the CDC or other entities may have said: “Because we don’t know, and because we do know that this thing is potentially deadly, you might consider wearing a mask outside.” I’m not trying to cast aspersions on the CDC; I may have well done the same thing they did with the facts that I had at hand. But I think the principle of communicating uncertainty, while uncomfortable, is extremely critical.

4. Use clear and simple language: I think we’ve done a pretty good job at this. These messages of: Wash hands, don’t touch your face, shelter in place—those things have been relatively uniformly communicated. I think what’s been less effectively communicated is at the next level up, which is at the municipal and government and state level. Why is it that there are some states that are not issuing these orders? How is that possible that we have such variation across states in terms of adherence? Is it that we aren’t speaking to the stakeholders, the decision-makers effectively? So while it’s important to communicate to the general population, there’s also an art and a science to speaking to policymakers about science.

5. Know your audience: Communication, by its very nature, is normally a bidirectional and reciprocal process. When you’re on a pulpit, you don’t have the luxury of getting feedback on what you’re saying. Good communication campaigns and plans have embedded in them key informants, focus groups, etc., that are representative of the general population. And you want to be field-testing your messages, you want to elicit the concerns of those stakeholders and audiences, so that you can then create either broad messages that are understood and actionable and resonate with everyone—or tailored messages for certain subgroups using your amplifiers.

As communication scientists, that is one of the most fundamental questions: Who’s your audience? And what do they say they need and want? Part of the problem here with all of this in terms of the communication plan, the spokesperson, the amplifiers, the focus groups; all that stuff that requires a lot of infrastructure and planning and capacity building that should already be in place, so when these events happen, we can kick into gear, right? And that’s an important lesson I think we’ve learned here, that the discipline of health communication needs to be invested in and the infrastructure and personnel need to be trained and ready to go.

6. Effectively harness social media: In a paper I contributed to for the American Journal of Public Health that’s currently in review, we showed how social media is phenomenally powerful at accomplishing a range of health communication functions. It can itself be a vector of contagion, in the sense of spreading misinformation, or it can be a means of protecting public health and transmitting very helpful messages. So social media as a communication vehicle has, in unprecedented ways, placed communication at the center of who gets to be healthy and who doesn’t. And so we really need to understand both the dynamics of social media as it relates to public health, as well as how to harness it to advance public health and not undermine it.

How can officials communicate effectively despite the fact that good, reliable science moves on a much different timeline than a global pandemic? Trials and peer-reviewed studies can take months and years.

So this question raises a larger issue in society of what I call science literacy. There is a dichotomous view that people have that either science knows everything or science knows nothing. In reality, science is not facts; it is a process of discovering or approximating truth. And it’s constantly iterative and refined as we learn more. So we need the general public to understand the scientific process. And that does take time. It may be a week’s time to study in a mouse, or it might be a year’s time to study a vaccine in the human. But people need to understand what [the scientific method] buys you, how incredibly helpful it is to use it in terms of approximating truth and how painstaking it is to do it. Because if you don’t do it, you really mess things up. You draw false conclusions. So that’s why shortcuts like Trump’s saying everybody should be taking hydroxychloroquine are profound, deeply disturbing mistakes.

All of this is hard enough to communicate to educated, affluent audiences. What special considerations should be taken when communicating health information to vulnerable communities?

There’s the basic messaging, and then there’s the question of: Now what? So we’re telling people to shelter in place, which may lead to other questions. How do they get food, for example? So one of the things that has to be done better in terms of public messaging is communicating to vulnerable populations in particular, what resources they have available to them to take care of the basic necessities of life during this crisis. What if you’re marginally housed? Where do you go? What if you’re marginally housed and you get sick and you have seven roommates, what do you do?

It’s getting into the weeds a little bit about a lot of the same common five or six common problems, such as, how do you get unemployment benefits? On those things, everyone is left to fend for themselves. It uncovers the fragmented social safety nets that we have in this country. Right now, I think the big gap is in, not so much COVID risks itself, but the health risks associated with the social distancing and sheltering in place. These policies have immediate effects on poor families and individuals.

So it’s important to communicate what is and is not available. And what are we doing to work on what’s not available? And be honest. Let’s just let’s not bullshit about it.