It was still dark when Veronica Perez arrived at Primex Farms, a nut-packing facility in California’s Kern County. Crickets murmured in the almond and pistachio groves stretching for acres in all directions. Once inside the building’s mirrored doors, Perez would usually stand next to other sorters alongside a conveyor belt, picking out blemished pistachios. But on June 25, at 4:30 a.m., Perez didn’t go in. Instead, for the next five hours, she and about 40 of her co-workers formed a picket line. More circled and honked in their cars. They held homemade signs with the names of co-workers who had the coronavirus. One sign in Spanish read, “The wise see danger and leave, but the foolish go on and suffer the consequences.” The employees chanted, “¡Somos esenciales!”: We are essential.

Perez, who is 42, had worked in California packing plants ever since she arrived from Mexico City 25 years ago, but she had never joined a walkout or protest. There hadn’t been many to join. But in recent months, things at Primex had become unbearable. In April, after employees requested the right to bring in masks to wear on the job, the company allegedly prohibited it. When it relented and allowed masks, it sold them for $8 apiece, according to several workers. (Primex denies ever selling masks.)

By May, employees at the 400-person plant were falling ill. Sick workers who stayed home went unpaid, so some kept coming to work with hacking coughs. Primex remained tight-lipped about any illnesses. When Perez asked the HR manager about a colleague who had contracted the virus, she recalled, the manager told her to “go home and stay there and not tell anyone about it.”

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

Remigio Ramirez, a 54-year-old maintenance worker, told his boss in mid-June that he wasn’t feeling well. The supervisor still encouraged him to come in since the team was already short-staffed. A few days later, Ramirez was diagnosed with COVID-19. He stayed home, isolating in his bedroom. “When I got up the next day, I didn’t see anyone—not my wife, not my daughters,” he says. “And I thought to myself, What’s happening? Did they leave me alone? But no, each one was in their room, sick.”

Over the summer, the coronavirus tore through the Central Valley, the vast, fertile interior of California that produces a quarter of the nation’s food, including 40 percent of its fruits and nuts. (Primex processes an estimated 6 percent of the state’s pistachios, most of which are exported.) By late July, the Kern County fairgrounds had been transformed into a federal surge testing site, and more than one in five coronavirus tests in the county were coming back positive. “The problem we’re seeing is not whether you’re going to get infected,” Armando Elenes, the secretary treasurer of the United Farm Workers (UFW), told me at the time. “It’s no longer a matter of if—it’s a matter of when.”

On June 23, Primex told a local news channel that 31 workers had tested positive for COVID-19. Employees who saw the broadcast were shocked: The company hadn’t told them about the cases, which it had confirmed about two weeks earlier. Ramirez seethed at the betrayal. “They said that they were going to let us know if anyone came down with it,” he says, “but they didn’t.” Primex didn’t comment on the alleged lack of communication to employees, but stated in an email: “We began implementing anti–virus spreading steps long before the CDC guidelines were published. We are proud to say that we are one of the cleanest and most sanitized plants in the industry.”

Remigio Rameriez, a maintenance worker at Primex Farms

Wesaam Al-Badry/Contact Press Images

Barely 5 feet tall, with an often-furrowed brow and a quiet voice, Perez never imagined herself becoming a labor organizer. “I’m not the loudest,” she admits, speaking through a translator. “I believe the message can be better communicated with control and poise.” Yet Perez knew what it looked like when a company turned a blind eye to its employees’ health. Years ago, she was injured at an almond packing plant and fired. A single mom of three kids, she suddenly found herself with no job and no medical help. “They use you until you can’t give any more of you—and once you have a problem, they’ll get rid of you like you’re nothing,” she says. She got through that crisis with support from Líderes Campesinas, an advocacy group for female agricultural workers. But it made her realize just how vulnerable she and her peers on the bottom rungs of the food system were. “I figured that if this happened to me, most likely it’s happening to many other women,” she says. Perez started attending Líderes Campesinas’ workshops on immigration law and workers’ rights, eventually volunteering with the group and joining its governing board.

The day the news of the Primex outbreak broke, Perez messaged the UFW’s Elenes, who created a WhatsApp group, called Justicia en Primex Farms, for concerned workers. (Primex isn’t unionized, but the UFW advocates for agricultural workers regardless of union status, Elenes says.) The next day, 100 people—a quarter of the facility’s workforce—had joined. That evening, they gathered on Zoom, many using the video platform for the first time, to plan a demonstration the following morning.

When dozens of her co-workers showed up for the walkout early on June 25, Perez was thrilled at the turnout and terrified of the possible consequences. She carried a sign listing three demands: sick pay, job protection, and respect. Ramirez, who had tested positive the week before, joined the protest from the confines of his car.

“Most workers prefer to always keep quiet for fear of losing their jobs or for fear of retaliation,” Perez said in a text message. “I was amazed myself at the quick response we got from our co-workers. It may be that everyone is tired of always staying silent.”

“¡Somos esenciales!” is a double-edged phrase: an overdue acknowledgment of the economic role immigrants play and a cudgel with which to keep them on the job. As the country went into lockdown in March, President Donald Trump declared that essential workers, including farmworkers, “have a special responsibility” to maintain normal work hours. Pickers and packers, including Primex employees, started carrying cards or letters from their employers identifying them as essential workers. “I am a farm worker helping to protect our food supply during the coronavirus pandemic,” read the letter a berry picker shared with me. “My job is considered essential so that we can produce food.” In theory, these pieces of paper, tucked away in pockets and wallets, could deter curious cops or ICE agents.

The federal government estimates that half of farmworkers are undocumented. The rate for food packers, like Primex’s employees, is thought to be lower than farmworkers’ but much higher than the overall workforce’s. These workers are critical to feeding the country, but deportable at the drop of a hat. The pandemic has only made this contradiction more manifest. Undocumented workers don’t benefit from federal coronavirus relief measures, such as expanded unemployment insurance. While federal legislation and policy expansions by California Gov. Gavin Newsom eventually granted essential food workers two weeks of paid sick leave, or “COVID pay,” enforcement has been spotty. “If an employer is not paying them covid pay, that sends a message to everybody else to not say anything,” Elenes says. And if an undocumented worker loses their job, they don’t get the standard unemployment stipend that federal or state relief promises to citizens. “Most employees accept that they don’t have health insurance. But not having any income? That’s not something they can resolve.”

Many agricultural workers carry letters from their employers identifying them as “essential” during the pandemic.

So begins a potentially deadly feedback loop: The fear of lost wages and deportation breeds silence, which in turn increases the risk of transmitting COVID. The mentality is, “If I feel good, even though I have the virus, I’m not going to tell you,” explains one farmworker in the Central Valley town of Lost Hills. “The farm supervisors aren’t interested in if you have it or not. You might feel sick, but it’s fine—as long as you don’t die.”

“People are scared to say anything—or they take it like it’s a common cold, and they continue going to work,” says a 46-year-old I’ll call Esperanza, who works at a nursery near Oxnard. The nursery wouldn’t give out masks, and her co-workers came in sick, knowing they wouldn’t get paid if they stayed home. Esperanza spoke to me over the phone in a quiet, cracking voice; just a couple of weeks before, she had come down with the coronavirus.

Even without this shroud of silence, agricultural workers are especially vulnerable to the pandemic. Some live in dormitories for temporary workers, where the virus proliferates. It’s common to carpool to job sites, which include greenhouses and packing houses with limited ventilation. Oil fields and freeways contribute to the Central Valley’s atrocious air quality; Bakersfield and Fresno have the worst particle pollution in the country. Rates of respiratory ailments like asthma and Valley Fever, a fungal lung disease, have soared. And for much of August and September, a ring of wildfires blanketed the fields in a hot, dense smog.

It’s no surprise that farmworker organizing and labor actions are a rarity. Less than 2 percent of farmworkers are unionized. “It just seems like an insane proposition to go out on strike,” says Lucas Zucker, communications and policy director of the advocacy group Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE). “Without a union who’s really organizing and providing support and assuring you of your legal rights, it can be really daunting. So it only does happen when people really reach a breaking point.”

As some pickers and packers reached that breaking point, there have been blips of COVID-related organizing up and down the West Coast. In the month before the Primex walkout, hundreds of fruit packers in Washington’s Yakima Valley left production lines to protest a lack of safety precautions and hazard pay. In Santa Maria, California, strawberry pickers walked off the job to protest wages falling just as many families were particularly cash-strapped. Blueberry pickers near Fresno also struck over a wage cut, standing by the fields waving red-and-black UFW flags.

Could the pandemic and the recognition of agricultural workers as essential begin to change the power dynamic between farmworkers and their employers? I took the question to Marshall Ganz, who once worked as the UFW’s organizing director and now lectures at the Harvard Kennedy School. “Where do you find courage to take risk? Grievances don’t generate courage. They generate anger or rage. They generate despair. So unless there’s some hope source, people don’t really engage,” he says. “Hope isn’t about certainty at all—it’s just about possibility.”

“So then the question is, under these conditions, are there unusual or new sources of possibility?”

The demonstration at Primex had an immediate impact: Within 24 hours, the company closed its processing facility for cleaning. Amid a flurry of local news reports about the outbreak, executives announced a plan to set up a mobile testing unit and implement other safety precautions, like installing Plexiglas dividers at the sorting tables, and more outdoor seating areas so employees could spread out during breaks.

When the plant reopened fully after a week, about 60 workers protested outside, alleging that Primex still wasn’t cleaning adequately or providing sick pay. But this demonstration lasted only a few hours. “We went back because we needed the work,” Perez says.

Meanwhile, suspecting that more people had been infected than the 31 that the company reported, employees started a coronavirus census, counting whoever had gotten sick. Primex is a 24-hour operation, and the texts to the group thread started coming in day and night; Elenes recalls waking up and finding message after message from upset employees. One woman reported that not only was she infected, she had exposed at least 16 family members. The youngest person in the Primex cluster was 6 months old.

In late June, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration opened an investigation. (It is ongoing, and OSHA did not respond to requests for comment.) By mid-summer, the employee-led count found that 97 of Primex’s 400 employees had tested positive, along with more than 60 family members. A week later, the mobile testing unit provided by the company would find that a total of 150 employees had been infected.

In mid-July, a 57-year-old Primex employee named Maria Hortencia Lopez was taken off life support. Perez had known Lopez as a lively co-worker who often brought in fruit to share and who asked after Perez’s kids. “I couldn’t believe that a person so full of life, such a happy and a good person, suddenly isn’t with you anymore,” she says.

Perez couldn’t shake the feeling that all of this could have been prevented. “That’s what hurts the most.”

The lack of basic workplace protections for farmworkers is by design. In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act, securing private sector employees’ right to collective bargaining and catalyzing an explosion of union membership. Under the law, workers could bring complaints of unfair labor practices to the newly created National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which could sanction offending employers. But Northern Democrats couldn’t pass the legislation without the support of Southern Democrats, who wouldn’t sign on to anything that threatened the racial hierarchy of Jim Crow. So lawmakers made a devastating concession: Packers, canners, and other “mechanical” food workers were covered by the NLRA, but farmworkers and domestic workers were not, effectively excluding two-thirds of the Black workforce from its benefits.

Three years after the passage of the NLRA came the Fair Labor Standards Act, which guaranteed a minimum wage and overtime pay. Again, to appease Southern Democrats, farmworkers and domestic laborers were excluded. These compromises, made to enshrine the legacy of slavery, continue to define conditions in the fields today. As Ira Katznelson wrote in his 2013 history of the New Deal, Fear Itself, “The South permitted American liberal democracy the space within which to proceed, but it restricted American policymaking to what I call a ‘southern cage,’ from which there was no escape.” Nearly century-old decisions are still shaping farmworkers’ lives, says Lori Flores, a historian of Latinx labor and politics at Stony Brook University: “What we’re seeing now is exactly what was happening in public discourse 100 years ago—this idea that farmworkers have always been this separate workforce that doesn’t need to be considered in federal protection.”

The official indifference toward agricultural workers persisted as their demographics shifted. During the Second World War, Mexicans were enlisted through the Bracero program to fill the labor void on farms and railroads. The program encouraged seasonal workers to come to the United States legally and reside in labor camps that were, in theory, supposed to meet health and labor standards, but in practice were unregulated, exploitative, and sometimes lethal. The program coincided with a rise in undocumented migrants, deemed “wetbacks” because many had forded the Rio Grande to enter the country.

For the food industry, the Bracero program was the root of “the arrogance that you will always have this bottomless reservoir of migrant labor,” Flores says. “Whether they are legal guest workers, undocumented, or citizens, migrant workers all feel the same kind of vulnerability to being fired, to losing their jobs, to not being able to advance within an industry or make a living wage.”

A 1951 report by the President’s Commission on Migratory Labor found that undocumented migrant workers suffered appalling work conditions, “grossly inadequate” housing, and “little opportunity to participate in influencing their wage rates.” “Since the ‘wetback’ has no legal rights he can make no demands, so is often preferred by the employer to the alien laborer brought in under intergovernmental agreement,” it stated. The report also noted that health problems disproportionately afflict migrant workers, issuing a warning that reverberates today: “The conditions contributing to this situation endanger not only the health of the migrant but that of the community as well.”

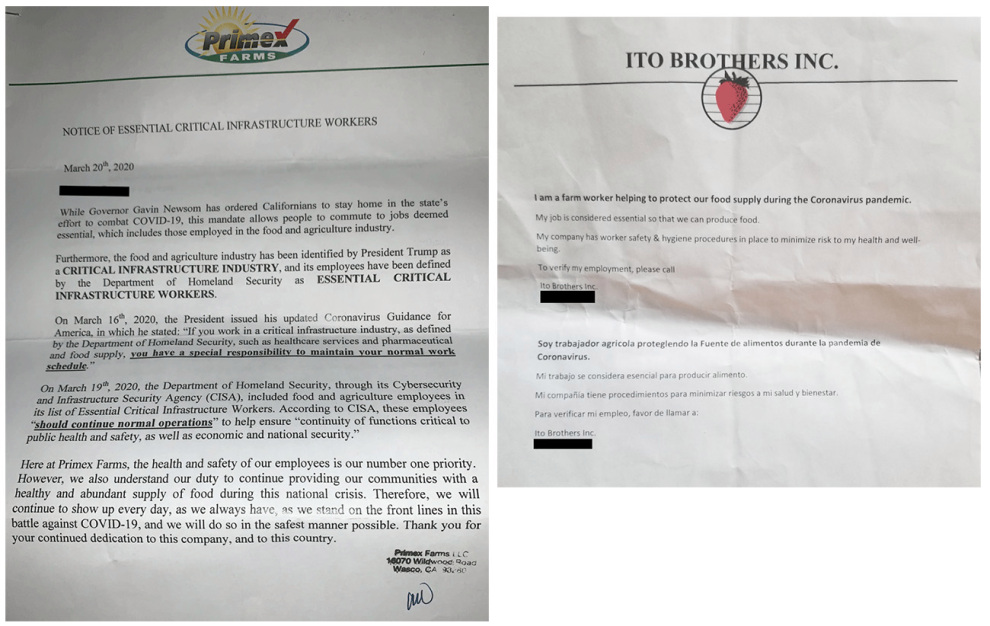

Day laborers in Lake Dick, Arkansas, 1938.

Russell Lee/Library of Congress

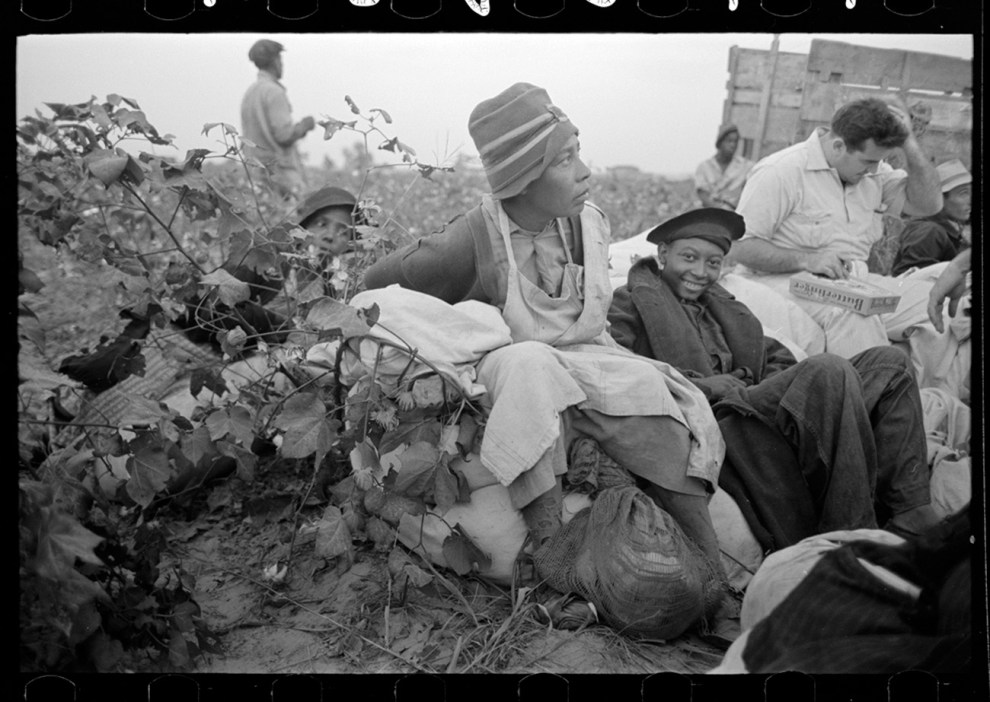

Mexican agricultural laborers arriving by train to help in the harvesting of beets in Stockton, California.

Marjory Collins/Library of Congress

The first contingent of Braceros disembark from buses at Calexico, Calif., May 19, 1965.

AP

Such was the state of things when Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and Larry Itliong established the United Farm Workers in 1966. The farm labor movement is often depicted as taking off thanks to Chavez’s singular charisma, but it also succeeded because it focused primarily on the rights of legal migrants and US citizens denied basic protections that other workers had enjoyed since the New Deal. “They took advantage of civil rights discourse and applied it and extended it to people who the average American wouldn’t normally think was undergoing their own civil rights struggles,” Flores says. Yet Chavez saw undocumented workers as strikebreakers, a threat to the movement he was trying to organize. He criticized growers who relied on them, and called for enhancing the Border Patrol; he also directed UFW workers to personally monitor the border. “As long as we have a poor country bordering California, it’s going to be very difficult to win strikes,” he said in a 1972 interview.

The UFW’s defining moment was its grape campaign: a series of boycotts, marches, and strikes demanding higher wages and union representation for California’s grape pickers. Many Americans first learned of the movement in 1966, when Chavez led hundreds of farmworkers on a 340-mile march through the Central Valley. The march began in Delano, just 15 miles from Primex.

Because farmworkers didn’t enjoy the protections of the National Labor Relations Act, they instead relied on secondary boycotts, encouraging consumers to avoid non-union produce. A vast network of organizers led protests outside grocery stores, distributing iconic UFW grape boycott pins. “It was all about getting the average housewife or the average shopper going into their grocery store to make a choice: not to buy non-union lettuce or grapes,” Flores says. “If they could just make that one choice, then even if they lived in New Jersey, or Minnesota, they could help farmworkers struggling in California.” Even dockworkers in Europe refused to unload American “scab grapes.”

The late ’60s and ’70s marked a brief golden era for the UFW. At its peak, the union was 50,000 members strong, having lobbied successfully for the 1975 California Agricultural Labor Relations Act, the first state law in the country allowing collective bargaining among farmworkers.

Those days were short-lived. California’s corporate growers found ways around the union contracts, restructuring after they expired so that a new union would have to be formed from scratch. In one common workaround still used today, growers set up trucks in the fields where freshly picked produce is packed by workers who can be categorized as “farmworkers” exempt from the New Deal protections. Free trade agreements, so-called right-to-work laws, and a host of Supreme Court decisions have made it even harder for farmworkers (and all workers) to form and join unions.

Cesar Chavez, leader of the National Farm Workers Association, stands with a group of striking workers in Delano, California.

Ted Streshinsky/Corbis/Getty

Yet much of the UFW’s fall was internal, fueled by Chavez’s increasing paranoia and refusal to decentralize power. After Chavez befriended the founder of the self-help cult Synanon, he subjected union leadership to “the Game,” a practice of spewing personal attacks in the name of therapy. “It began to cut the heart out of the union: purges, witch hunts, all of that stuff,” Ganz recalls. “The worst thing was that worker leadership who wanted to try to step up…were treated as traitors, and they were fired.” The union went into a downward spiral as key members left and fewer contracts were renegotiated. When civil wars in Central America led to mass migration to the United States in the 1980s, the UFW didn’t make overtures to bring the new arrivals into the fold, Flores says. “Its intense anti-‘wetback’ rhetoric was really damaging,” she says. In the following years, wages dropped, fringe benefits dried up, and living conditions worsened, Flores notes in her history of California farm labor, Grounds for Dreaming.

Today, there are roughly 1 million hired farmworkers across the country; the UFW represents just 7,500 of them. In many ways, pickers and packers face the same conditions as the grape strikers did in the 1960s—a model “rooted in plantation economics,” as Zucker, of CAUSE, put it. Only five states entitle farmworkers to overtime pay. In New York, overtime for farmworkers is defined as more than 60 hours a week. Lawmakers “are still pushing the boundaries of trying to make farmworkers seem like they’re not like other types of workers—that they can stay treated differently, and their bodies can stand to undergo more harm,” Flores says.

Even in California, where farmworkers have the right to collective bargaining and overtime pay, “the laws on the books aren’t the laws in the fields,” Zucker says. In theory, workers can complain to the state division of occupational safety and health, but in practice, aggrieved workers, who may be undocumented, poor, and not native English speakers, find the process difficult to navigate. Hazel Davalos, the community organizing director at CAUSE, says her group refers people with complaints to the state agency, but “if the worker doesn’t chicken out the moment they ask for their name, will Cal/OSHA actually come when their nearest office is like three hours away? Probably not. And if they’re strapped for resources? Probably not. And during a pandemic? Forget about it.”

Fixing this undeniably broken system would require legislation to improve and expand federal worker protections. But in the absence of the political will to do that, Flores says, a lot could be gained from taking a page out of the UFW’s old playbook for mobilizing consumer choice. Florida’s tomato industry provides something of a model. A decade of organizing by the Coalition of Immokalee Workers led to the creation of the Fair Food Program, which ensures workers on participating farms a penny-per-pound premium on top of minimum wage and basic safety standards like shade and water. Farm owners are guaranteed business from sellers, who can boast about their ethical practices to consumers. The program has gotten buy-in across the supply chain, including big customers like Taco Bell and Walmart. “I want to see Fair Food programs expand to not only other food items, but to also bring back that idea of visual power,” Flores says. “I’d love to see it more in grocery stores.”

Shoppers already know what labels to look for to make sure their produce is pesticide-free and their chickens had space to roam. What if that same transparency applied to the workers who harvested and packaged their food? And what better time than now—as Americans hang signs thanking essential workers of all stripes—to make amends for the decades that farmworkers have been denied a seat at the table?

In other parts of the food industry, workers have seized this moment to demand—and secure—change. The spring brought a series of deadly, highly publicized coronavirus outbreaks in meatpacking plants across the country. As of mid-December, more than 50,000 meatpacking workers had contracted the virus, 262 of whom have died, according to the Food and Environment Reporting Network. The spring was “horrendous at best,” says Mark Lauritsen, director of the food processing and meatpacking division of the United Food and Commercial Workers, which represents 70 percent of beef workers, 60 percent of pork workers, and a third of poultry workers.

In the calamity—and the outpouring of public sentiment that came with it—Lauritsen and his colleagues saw an opening. They busied themselves pushing through labor standards and wage increases at unionized JBS, Cargill, and Smithfield facilities. Union activists were able not only to secure hazard pay, but to make it into a permanent fixture. Now, the base hourly pay at some union shops has increased by $2; at several plants, the lowest-paid workers make between $18 and $20 an hour. “If these plants were going to be able to attract and retain workers in a pandemic, quite honestly, they just had to do it,” Lauritsen says. “They couldn’t afford a massive wave of disruptions during this time. So it was just a matter of leverage and time.” Still, Lauritsen acknowledges that “those folks on farms have struggled with the same issues that essential workers across this country have—they’ve just been left out because the law is set up against them.”

The challenges farmworkers must surmount to eke out even modest gains were evident during a protest last spring at Rancho Laguna, a raspberry and strawberry farm in Santa Maria, California, that supplies the berry giant Driscoll’s. In May, pickers walked off the job to protest changes to quality standards that slowed workers down, effectively lowering their wages. The action didn’t last long after Rancho Laguna called the local sheriff’s office. No one was arrested, but the sight of uniformed officers in the fields was enough to put an end to the walkout. When workers tried to deliver a petition to a Driscoll’s facility, the company also called the cops.

CAUSE helped the workers, who are not unionized, file a complaint with the state and put together an online petition signed by 60,000 people. The group also warned the farm owner, who happened to be a Santa Barbara County planning commissioner, that they would attend his next public commission meeting if he didn’t meet with them. The petition’s success appears to have done the trick: Driscoll’s president got on the phone with workers, and the farm owner agreed to increase the rate to $2.10 per flat. Driscoll’s noted that it “had limited involvement regarding the wage discussions as that would have interfered with the operations of the separate and independent business of Rancho Laguna Farms.” In a public statement, Rancho Laguna’s owner promised to ensure that workers feel safe, adding that he should have met with his employees before calling the sheriff.

After all that, wages increased by about $13 a day. While the result was ultimately a win, it also underscored how much organizing it takes to “get even the most bare bits of human dignity in the workplace” for farmworkers, Zucker concedes. “It’s unclear to me how long that public sympathy will last after the pandemic—and if that’s long enough to really make systemic change.”

Following the summer’s wins for workers, the atmosphere at Primex became increasingly oppressive. In late July, about a month after the first protest, dozens of workers lost their jobs when Primex ended its contract with a temporary staffing agency. The company attributed the reduction to typical seasonal changes, but according to employees and the UFW, the cuts included many of the employees most critical of Primex’s pandemic response. “Everyone knows why those employees were fired,” Perez says. “They put their health at risk. And even after they got sick, and after they got better, they were fired.”

Workers arriving at the Primex facility early in the morning.

Wesaam Al-Badry/Contact Press Images

Primex brought in new workers the same day, according to the UFW, which filed a complaint about the firings with the NLRB. (The case is open; Primex didn’t comment on it but said of the UFW, “all they do is just play the blame game without any accountability.”) When the board decides, the fired workers will likely have moved on, says Elenes. “They just delay, delay, delay, so by the time you actually win, it’s a really hollow victory.”

Perez and Ramirez say they were separately called into meetings that included Primex’s manager of human resources and were instructed to retract statements they’d made to the media. The company would close because of all the bad press, a manager said, and if it went down, it would be because of employees like them. “They said, ‘This company should mean something to you,’” recalls Ramirez, who has worked at Primex for 13 years. The HR manager told Perez that “her head was hurting from hearing me talk so much, and she didn’t want to hear from me anymore.” (A complaint to the NLRB accuses Primex of “making coercive statements to employees.” Other complaints allege that Primex retaliated by giving Ramirez a more demanding schedule, and by demoting Perez to on-call status.)

In July, one of Perez’s colleagues tried to record a video inside the plant showing that social distancing and mask-wearing weren’t happening consistently. Primex disciplined the employee, according to another NLRB complaint, and the company required workers to sign a policy prohibiting video recording on-site. Perez refused to sign. “That’s when [the production manager] pulled me into the office. He likes to scream a lot,” she recalls.

“I’m very short, and he’s tall,” Perez said in a virtual panel put together the same day by Líderes Campesinas. She began to weep. “It makes me want to cry because my co-workers…I’ve tried to be really strong in front of them, but I can’t anymore.” When they spoke up, things got worse. “We’re only asking for a safe place to work,” she exclaimed. “What do we have to do?”

In theory, Primex workers could form a union. But with so many vocal workers gone, and others exhausted and afraid of retaliation, there’s not much appetite for the lengthy unionization process. Elenes often runs into this roadblock: Workers put in so much energy to get the basics like masks or an extra 20 cents per flat of strawberries, that the organizing peters out after the first win. “It’s short-term thinking. And employers know this,” he says. “But the issues usually are much bigger and deeper than that. And that requires a much bigger commitment, which sometimes they’re not ready for.”

Fifty years ago, with the farmworkers’ movement ascendant, the conditions at Primex “would have been an invitation to organize,” says Ganz, the former UFW organizer. “There’d be a grievance, and people would call out the union to come and help.” Today, it’s much harder to see how conditions will get better anytime soon. There’s no shortage of reasons for anger or despair. Are there any sources of hope?

When I put the question to Perez, I feel silly even asking it. To my surprise, she responds with a resounding yes. “Hope never dies,” she says, as if stating the obvious. “It doesn’t matter if I get fired. It doesn’t matter if I get yelled at. Nothing will make me quiet my voice.” At the same time, she is clear-eyed about the pace of progress. “I understand that this probably isn’t going to be beneficial for me or my co-workers—probably not even in our generation.” If history is any guide, it could take decades for her labor to bear fruit.

This article was featured in Mother Jones’s January/February 2021 print issue, and has been updated to reflect research and editorial changes.