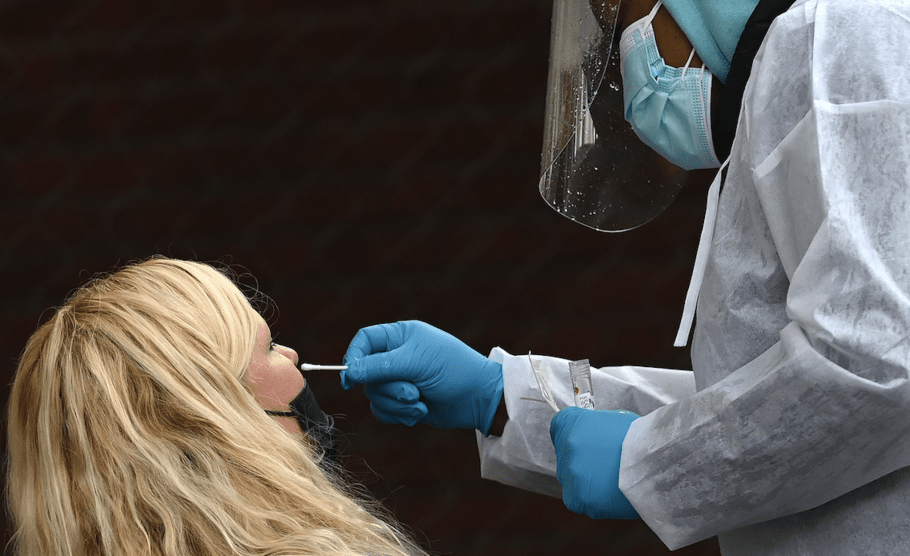

A healthcare worker swabs a patient during a drive up rapid COVID test in West Des Moines.Jack Kurtz/Zuma

This story was published originally by ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica‘s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

The promise of antigen tests emerged like a miracle this summer. With repeated use, the theory went, these rapid and cheap coronavirus tests would identify highly infectious people while giving healthy Americans a green light to return to offices, schools and restaurants. The idea of on-the-spot tests with near-instant results was an appealing alternative to the slow, lab-based testing that couldn’t meet public demand.

By September, the US Department of Health and Human Services had purchased more than 150 million tests for nursing homes and schools, spending more than $760 million. But it soon became clear that antigen testing—named for the viral proteins, or antigens, that the test detects—posed a new set of problems. Unlike lab-based, molecular PCR tests, which detect snippets of the virus’s genetic material, antigen tests are less sensitive because they can only detect samples with a higher viral load. The tests were prone to more false negatives and false positives. As problems emerged, officials were slow to acknowledge the evidence.

With the benefit of hindsight, experts said the Trump administration should have released antigen tests primarily to communities with outbreaks instead of expecting them to work just as well in large groups of asymptomatic people. Understanding they can produce false results, the government could have ensured that clinics had enough for repeat testing to reduce false negatives and access to more precise PCR tests to weed out false positives. Government agencies, which were aware of the tests’ limitations, could have built up trust by being more transparent about them and how to interpret results, scientists said.

When health care workers in Nevada and Vermont reported false positives, HHS defended the tests and threatened Nevada with unspecified sanctions until state officials agreed to continue using them in nursing homes. It took several more weeks for the US Food and Drug Administration to issue an alert on Nov. 3 that confirmed what Nevada had experienced: Antigen tests were prone to giving false positives, the FDA warned.

“Part of the problem is this administration has continuously played catch-up,” said Dr. Abraar Karan, a physician at Harvard Medical School. It was criticized for not ensuring enough PCR tests at the beginning, and when antigen tests became available, it shoved them at the states without a coordinated plan, he said.

If you tested the same group of people once a week without fail, with adequate double-checking, then a positive test could be the canary in the coal mine, said Dr. Mark Levine, commissioner of Vermont’s Health Department. “Unfortunately the government didn’t really advertise it that way or prescribe it” with much clarity, so some people lost faith.

HHS and the FDA did not respond to requests for comment.

The scientific community remains divided on the potential of antigen tests.

Epidemic control is the main argument for antigen testing. A string of studies show that antigen tests reliably detect high viral loads. Because people are most infectious when they have high viral loads, the tests will flag those most likely to infect others. Modeling also shows how frequent, repeated antigen testing may be better at preventing outbreaks than highly sensitive PCR tests, if those tests are used infrequently and require long wait times for results. So far, there are no large scale, peer-reviewed studies showing how the antigen approach has curbed outbreaks on the ground.

People need to realize that without rapid testing, we’re living in a world where many people are unknowingly becoming superspreaders, Karan said. About 40 percent of infections are spread by asymptomatic people with high viral loads, so antigen tests, however imperfect, shouldn’t be dismissed, he said.

Even those who are more skeptical said they can be helpful with a targeted approach directed at lower-risk situations like schools, or outbreaks in rural communities where PCR is impractical, rather than nursing homes where a single mistake could set off a chain of deaths.

It is “completely irresponsible” to take a less-accurate test and say it applies to all situations, said Melissa Miller, director of the clinical microbiology lab at the University of North Carolina.

There’s no precedent for the government to bet this much on a product before it’s been thoroughly vetted, said Matthew Pettengill, scientific director of clinical microbiology at Thomas Jefferson University. “They put the cart before the horse, and we still can’t see the horse.”

The Government Quickly Embraced an Unproven Test

During a public health crisis, the FDA can issue emergency use authorizations to make tests available that might otherwise have been subjected to many months of scrutiny before being approved. The three most popular antigen tests in the US, from Abbott Laboratories, Quidel and Becton, Dickinson, commonly known as BD, had to submit far less proof of success than is usually required.

FDA gave the first authorization to Quidel on May 8 based on data from 209 positive and negative samples. BD got its permit July 2 with a total of 226 samples and Abbott in late August with 102. Outside of a pandemic, the agency might otherwise have required hundreds more samples; in 2018, BD’s antigen test for the flu provided data on 736 samples.

There’s no excuse for the small pool of data, particularly for Abbott, Pettengill said. At the start of the pandemic, the FDA authorized PCR tests based on as few as 60 samples because it was difficult to find confirmed cases. By the time Abbott got its authorization in August, it was “a completely different ballgame.” Abbott’s validation document states the company collected swabs from patients at seven sites. Given the case counts over the summer, it should have only taken a few days to collect many hundreds of samples, Pettengill said.

Abbott didn’t respond to requests for comment. Quidel pointed ProPublica to an article in The New England Journal of Medicine that explained how regular antigen testing can contain the pandemic by identifying those who are most infectious.

“We have full confidence in the performance” of our test, Kristen Cardillo, BD’s vice president of global communication, said in an email. BD “completed one of the most geographically broad” clinical trials for any antigen test on the market, she added, by “collecting and analyzing 226 samples from 21 different clinical trial sites across 11 states.”

The day after the Abbott test was authorized, HHS placed a huge bet on it, buying 150 million tests.

Then, it gave institutions like nursing homes advice on how to use them off-label, in a way in which they were untested and unproven.

The three tests are authorized for the most straightforward cases: people with COVID-19 symptoms in the first week of symptoms. That’s how they were validated. They produced virtually no false positives that way and were 84 percent to 97 percent as sensitive as lab tests, meaning they caught that range of the samples deemed positive by PCR.

Yet HHS allowed their use for large-scale asymptomatic screening without fully exploring the consequences, Pettengill said.

A recent study, not yet peer reviewed, found the Quidel test detected over 80 percent of cases when used on symptomatic people and those with known exposures to the virus, but only 32 percent among people without symptoms, The New York Times reported.

The HHS encourages nursing homes that can’t get access to PCR tests to use antigen tests, even on asymptomatic people. The agency suggested repeat testing to reduce false negatives but didn’t mention false positives.

An October survey found that nearly a third of nursing homes had left the federally provided antigen tests untouched, The Wall Street Journal reported. Staff cited time-consuming paperwork for federal reporting requirements and skepticism about their accuracy.

“I think a lot of the trust was lost, unfortunately,” Karan said.

“Be Prepared for Some ‘Pressure'”

As antigen tests began to give false positive results in nursing homes, state public health officials in Vermont and Nevada pushed back. But HHS officials overruled their concerns and pressured them to keep using the tests.

In July, an urgent care clinic in Manchester, Vermont, discovered that, of 64 patients (mostly asymptomatic) who the Quidel test said were positive, only four, all symptomatic, got a positive PCR result. As reported by the Vermont alt-weekly Seven Days, Quidel said the fault lay with the PCR tests. The FDA also pointed a finger at the PCR “without any foundation of evidence,” Levine, the state health commissioner, told ProPublica.

There was a potential problem related to the PCR machine’s software, but Vermont’s state lab retested the samples after upgrading the system and found no change in results, Levine said. State officials also conducted pop-up testing in the Manchester region and found just a handful of positives out of 1,600 tests, he said, proving that there was no outbreak in the community.

Levine said his health agency ended up labeling the 60 samples as “discordant” instead of “false positives” and left them out of the official case count. “We didn’t want hard feelings,” he said. “I do think this administration wanted to show it was doing something … and this [antigen test] is one way to demonstrate that.”

The federal government defended Quidel again in early October. The Times reported that Nevada’s Health Department ordered nursing homes to stop using all antigen tests after reviewing results from 3,725 tests. Nursing homes had double-checked 39 samples the BD and Quidel tests flagged as positive, but 23 of them tested negative via PCR. Nevada’s letter noted that it only learned about the problem because the state chose to go above and beyond federal guidelines: The FDA had said there was no need to double-check positive results. State officials told nursing homes to continue using PCR to fulfill testing requirements.

Cardillo, the BD spokesperson, said a “very small number” of the 11,250 nursing homes using BD tests reported higher than expected false positives, and “we are conducting thorough investigations into those cases.”

When an official from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services asked why the state adopted a ban, a Nevada health facilities inspector said false positives could put nursing home residents at risk, according to emails obtained by ProPublica via a public records request.

If someone tests positive on an antigen test, the nursing home may sequester the patient with other residents who are truly infected, the Nevada official, Bradley Waples, wrote. If that person later has a negative PCR test, then the faulty diagnosis will have placed them “in danger of contracting the virus by introducing them to a room full of actual positive residents.”

His email didn’t explain whether anyone had been infected that way. A spokesperson from the Nevada Health Department declined to comment.

In one nursing home, the antigen tests found seven positives out of 35 samples, yet all seven tested negative by PCR, Waples wrote. Two other states had reported similar false positive problems, he added.

“Thanks Brad,” the CMS official replied. “It’ll be interesting to see what HHS does with this information. Be prepared for some ‘pressure.'”

That pressure arrived two days later in a letter from HHS, where Assistant Secretary Brett Giroir ordered Nevada to rescind the ban. You “must cease immediately or appropriate action will be taken against those involved,” he wrote. Nevada complied.

Giroir’s letter cited some of the key arguments for antigen tests, including their ability to detect those who are most infectious. Yet the agency’s reasoning glosses over many unknowns. Some people can become acutely ill without ever showing high viral loads, or only doing so briefly, said Miller, the North Carolina scientist. Those with lower viral loads may still be able to infect others, and the data is murkier for asymptomatic people, she added.

“I’m not saying it’s right or wrong, but we’re not fully understanding how these tests perform in certain populations, and yet they’re being used,” Miller said.

“It’s a test, yes, but there are people on the other side of that test,” she added. If you have a family member in a nursing home that’s getting false positives, it takes time to confirm results by PCR, Miller said. “These are days in which the residents and their families have an incredibly high level of anxiety and worry about their loved ones.”

America Needs a National Antigen Testing Plan

The initial vision of giving every American at-home tests every day has been slow to materialize. Many of the available antigen tests require machines to read the results or someone who’s trained to administer the test. Some states aren’t even reporting their antigen results, so it’s unclear when they’re used or how they complement PCR.

“We need a federal plan for who gets tested, with what tests … when, how often, and what data should be reported back, and what those data pieces mean,” said Dr. Rebecca Lee Smith, an epidemiology professor at the University of Illinois.

So much remains unknown about the best way to use antigen tests, Smith added. If you have a million tests, is it better to test a million people once, or test half a million people who are at high risk twice, or test essential workers five or 10 times? “It’s how you use the tests, not just how many tests you have.”

The US has never had a national testing strategy, said Dr. Ranu Dhillon, an expert on rapid testing and global health equity at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The administration’s haphazard approach to antigen tests is an extension of that larger failure, he said.

While there have not been well-publicized examples of false negatives that have led to outbreaks, one risk that’s been overlooked until recently is the probability of false positives in low-prevalence communities—places where few people have the virus, Miller said.

Even if a test is very “specific” (providing few false positives), it can flag more false positives than true positives. This happens for both PCR and antigen tests, but if antigen testing scales up to tens or hundreds of millions of tests a month, communities and institutions could get overwhelmed, Miller said.

One paper from August found that if a quarter of American school kids were tested three times a week with an antigen test that’s 98 percent specific, it would produce 800,000 false positives a week that need to be double checked by PCR tests. (For reference, the US is processing an average of 1.4 million tests per day, nearly all of them PCR).

Miller said she’s received confused phone calls from doctors asking for advice. She helped a state task force create a flowchart that explains how to interpret antigen results and when to do repeat testing. “But why are 50 states doing this,” instead of a single clear message from the administration? Miller asked.

Karan, the Harvard physician, said federal officials need to set expectations. An employer who can’t afford PCR might welcome antigen testing, because catching 80 percent of infected workers would be better than catching none at all. Meanwhile, anyone who gets a single negative result shouldn’t use it as an excuse to go to a bar, he said, and they should understand they might test positive a couple days later. This is particularly crucial for the many who plan to rely on antigen tests results to clear them for Thanksgiving gatherings.

Smith said any testing plan must be paired with a strong program of contact tracing, isolation and quarantine. The reality in this country is that “just telling someone they’re positive has not been enough. There has to be a cultural shift.”

As Reuters reported, Slovakia drove down its infection rate through a mass antigen testing program that imposed strict quarantine rules. The country tested 65 percent of its population in one weekend, then repeated the tests in hot spots a week later. Anyone who refused testing had to stay home, while those who tested negative got certificates that let them participate in public life.

That approach wouldn’t be feasible in the US, Smith said. “We need to instead think about empowering and supporting people to abide by isolation and quarantine.”