Drew Angerer/Getty

For years, Purdue Pharma has maintained that it can’t be blamed for the overdose crisis that unfolded after its introduction of OxyContin—but a trove of new evidence suggests that the company was instrumental in laying the groundwork for the opioid epidemic.

As early as 2000, Purdue collaborated with pain patient advocacy groups and professional pain management organizations to create what former president Richard Sackler called a “pain movement.” The company also allegedly worked with competitor and opioid maker Johnson & Johnson, which was recently found liable for contributing to the opioid crisis in Oklahoma, in an effort to create a “pain management franchise.” In addition, company executives appear to have met with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to discuss possible collaborations.

These revelations come from new exhibits in the federal litigation bundling roughly 2,000 cases against opioid makers and distributors that is set to go to trial in October. The plaintiffs allege that the pharmaceutical companies worked together in a conspiracy to sell more opioids, an allegation that the defendants vigorously deny. Under the terms of a recently-leaked settlement proposal, Purdue and its owners, the Sackler family, may soon settle all the claims brought against the company by thousands of state and federal lawsuits.

Here are some highlights from the recently unsealed exhibits:

“They are going to have to learn to live with ‘industry’ reps on their board”

In order to promote opioids, pharmaceutical companies funded a number of professional and patient advocacy organizations to serve as “front groups,” according to the plaintiffs, including the now defunct American Pain Foundation and the American Pain Society. Some of the groups went on to issue guidelines minimizing the risks of opioid addiction, lobby to change laws aimed at curbing opioid abuse, and protect doctors sued for overprescribing painkillers, according to an investigation by former Missouri Sen. Claire McCaskill (D).

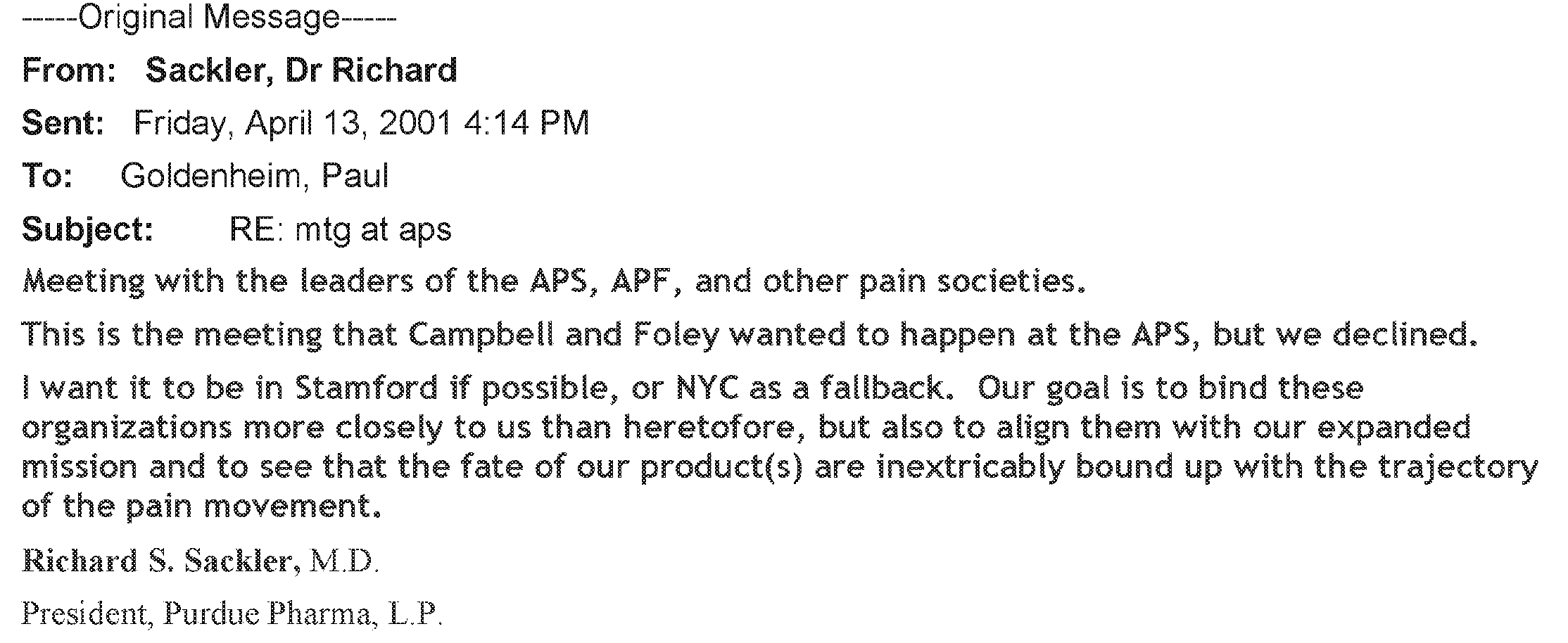

The new exhibits suggest Purdue’s motives in collaborating with these organizations. In a 2001 email conversation with colleagues about meeting with patient advocacy groups, Purdue president Richard Sackler wrote, “Our goal is to bind these organizations more closely to us than heretofore, but also to align them with our expanded mission and to see that the fate of our product(s) are inextricably bound up with the trajectory of the pain movement.”

A screenshot of email correspondence published in the multi-district opioid litigation.

Purdue executive Robin Hogen allegedly stated in a 2000 memo that if the American Pain Society “want our bucks (and they honestly cannot survive without industry support) they are going to have to learn to live with ‘industry’ reps on their board. I don’t think they can expect huge grants without some say in governance.” (Hogen said that the memo showed “some naiveté on my part and a little bravado…from a new employee.” He added that Purdue did not heed his advice, and, in an email to Mother Jones, Purdue denied controlling the organizations it sponsored. The American Pain Society filed for bankruptcy in July.)

Collaborating with Johnson & Johnson to create a “Pain Management Franchise”

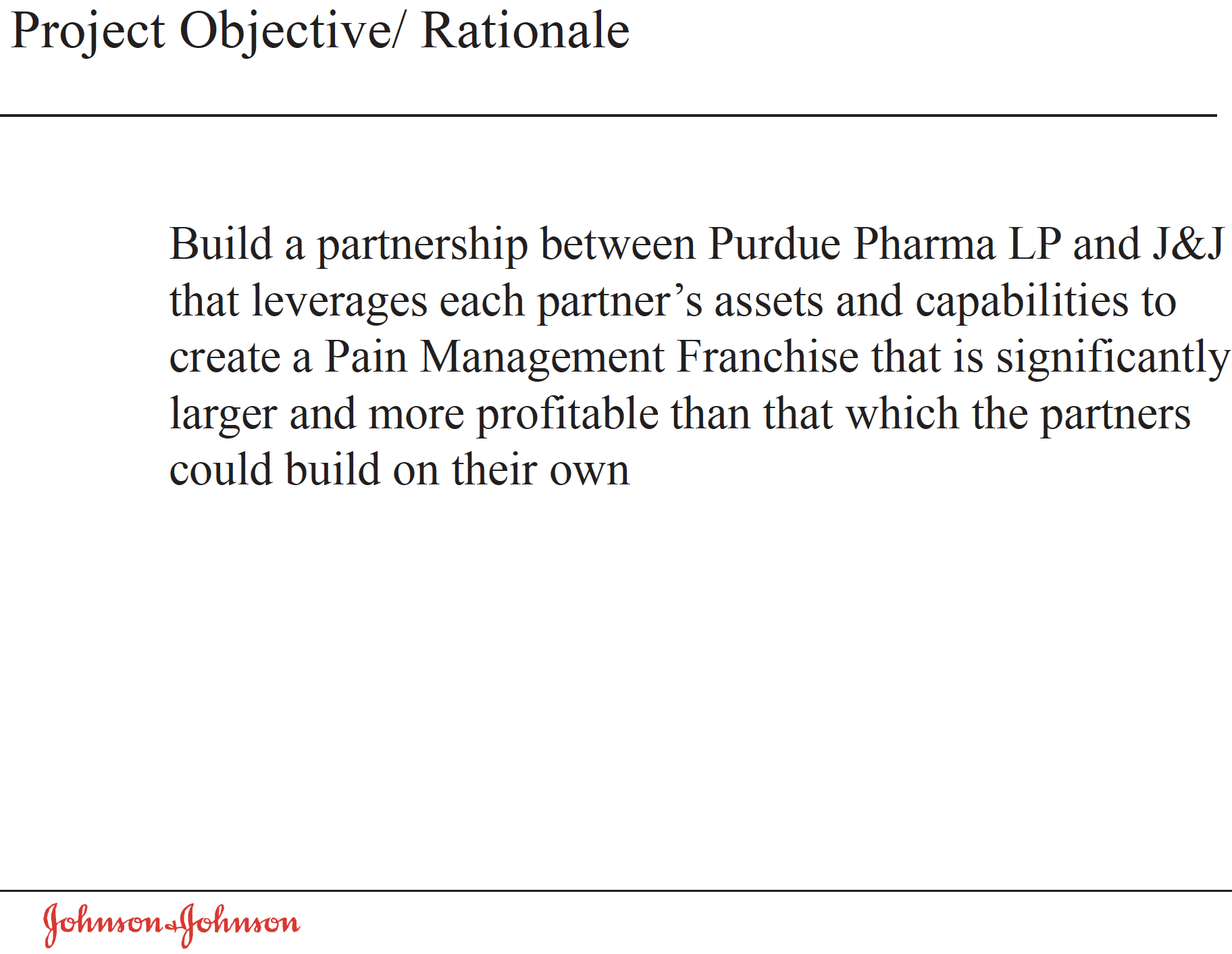

According to the court documents, as early as 2000, Purdue began working with Johnson & Johnson, whose pharmaceutical subsidiaries sold opioids Duragesic and Ultram, on a “co-promotion agreement” in which sales representatives would promote both companies’ opioid products. The ultimate goal, according to a J&J presentation, was to “Build a partnership between Purdue Pharma LP and J&J that leverages each partner’s assets and capabilities to create a Pain Management Franchise that is significantly larger and more profitable than that which the partners could build on their own.”

A screenshot of a J&J presentation regarding a possible collaboration with Purdue

The co-promotion agreement never came to fruition, but evidence suggests that the companies instructed their sales representatives not to attack the others’ brands. In 2001, after an executive from J&J subsidiary Janssen complained that Purdue’s sales representatives were telling doctors about the abuse of Janssen’s opioid, Duragesic, a Purdue executive instructed Purdue’s sales force not to discuss abuse and diversion of OxyContin or Duragesic. If they did, the letter stated, there would be consequences: “Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Purdue have agreed that should either company have representatives who promote product out of label or out of policy, the name of the representative will be provided to the other company for investigation and disciplinary action if needed.”

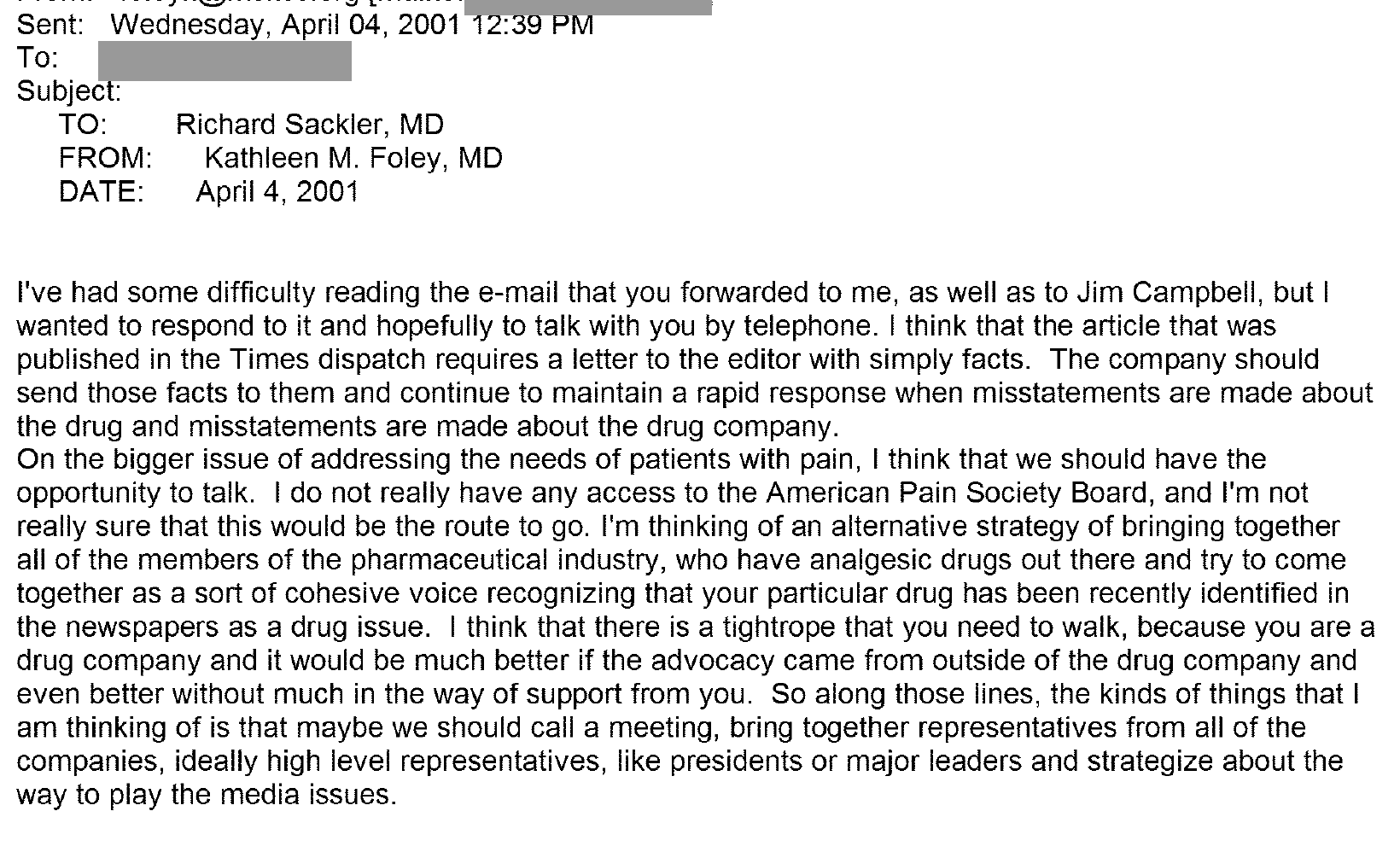

“It would be much better if the advocacy came from outside of the drug company”

In 2001, shortly after the first media reports of widespread abuse of OxyContin, Dr. Kathleen Foley, a neurologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York and a former paid speaker for Purdue, emailed Richard Sackler urging the company to collaborate with other pharmaceutical companies. “I’m thinking of an alternative strategy of bringing together all of the members of the pharmaceutical industry, who have analgesic drugs out there and try to come together as a sort of cohesive voice recognizing that your particular drug has been recently identified in the newspapers as a drug issue,” she wrote. “I think that there is a tightrope that you need to walk, because you are a drug company and it would be much better if the advocacy came from outside of the drug company and even better without much in the way of support from you.”

A portion of Foley’s email to Sackler

In 2005, Purdue lobbyist Burt Rosen allegedly organized the Pain Care Forum. Purdue, J&J, and the American Pain Foundation were among the group’s early participants, but, according to court documents, the forum soon included virtually every major opioid maker and distributor. “I think this could fill the vacuum of leadership in the community at large, and provide for some unified direction on issues of importance to the pain community,” Rosen allegedly said. The forum—which has no public website, meeting notes, or member list—served as a platform for industry to discuss issues related to opioid supply and coordinate media and policy campaigns.

When the CDC proposed guidelines urging doctors to limit opioid prescribing, the group mounted a coordinated, seemingly-grassroots effort to criticize the guidelines using “media efforts and recruiting patients and provider experts,” according to court documents. Though Rosen denied that the forum itself hires lobbyists, the forum’s members allegedly spent nearly $900 million to influence government between 2006 and 2015.

Purdue’s Work with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Among the unsealed exhibits is a memo submitted by Purdue’s Robin Hogen describing a July 2000 meeting between Purdue executives and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation president Dr. Steve Schroeder. The foundation, started by and named after J&J’s former leader, is the nation’s largest philanthropic organization focused solely on public health. At the time, about 60 percent of the foundation’s holdings were in J&J stock.

Hogen wrote,

They were impressed with the scope of our programs and invited Purdue to join the national coalition they are forming to improve care and caring at the end of life (called the Last Acts Partnership). We would be the only for-profit company in that category. Dr. Steve Schroeder, President of the RWJ Foundation, indicated that they rarely sit down with pharmaceutical companies to discuss areas of mutual interest. He was impressed when we described the unbranded, non-promotional aspect of our speakers bureaus and symposia and seemed quite interested in keeping the lines of communications open for possible future partnerships.”

The memo notes that “areas of possible future collaboration” include setting up “Purdue Faculty Fellowships,” “help in identifying pain management advocates,” and “sponsorship of a session on pain management” at an annual foundation meeting. The memo ended, “I believe this is a relationship that could yield many happy returns to both Purdue and RWJ.”

Hogen, who later worked in communications for Yale and the RWJ Foundation, told Mother Jones that the meeting was part of a company effort to reach out to organizations “who shared our interest in treating chronic pain patients humanely.”

None of the collaborations mentioned in the memo came to be; the foundation “subsequently declined opportunities to collaborate with Purdue on programs related to pain assessment and pain management,” according to RWJ spokesman Jordan Reese. “We are working alongside others—and across disciplines—to address the many factors that lead to addiction, as well as to advance policies and practices that will prevent another such crisis from occurring,” he said. Today, about 15 percent of the foundation’s holdings are in J&J stock.

“Make the whole pie bigger, not only for us but for our competition as well”

In 2000, Purdue held a sales meeting in Palm Beach, at which an executive named Mark gave a speech welcoming the sales representatives. Below is part of Mark’s script, included in the unsealed exhibits:

(MARK SHOULD ENTER WEARING SUNGLASSES)

… You know, it’s always hot here in Palm Springs. That’s why it’s a perfect place to have our meeting … because we’re hot … we’re burning up the competition with our sales of OxyContin! Do you know it’s now the number one prescribed opioid brand in the U.S.?

“Now, you’re probably wondering what else can be done to sell even more OxyContin,” Mark went on. “There are also some things we’re cooking up for the coming year to help you and OxyContin and the whole pain market as well.” These initiatives allegedly included collaborating with the American Pain Society to develop materials that would “be distributed to hospitals across the country” and “weekly feature stories about pain and its management in newspapers.” The goal, said Mark, is to “raise awareness of undertreated pain” and to “Make the whole pie bigger, not only for us but for our competition as well.”

Mark concluded,

I hope you enjoy your stay here in Palm Springs, I know I will. Enjoy the weather … because let me tell you, OxyContin’s continuing success, is going to make every part of this country from Seattle to Detroit to New Orleans as hot as it is here in Palm Springs this winter for every one of you. You are the force for the future … let’s make it happen! (PLAY SONG HOT, HOT, HOT)

This article has been updated.