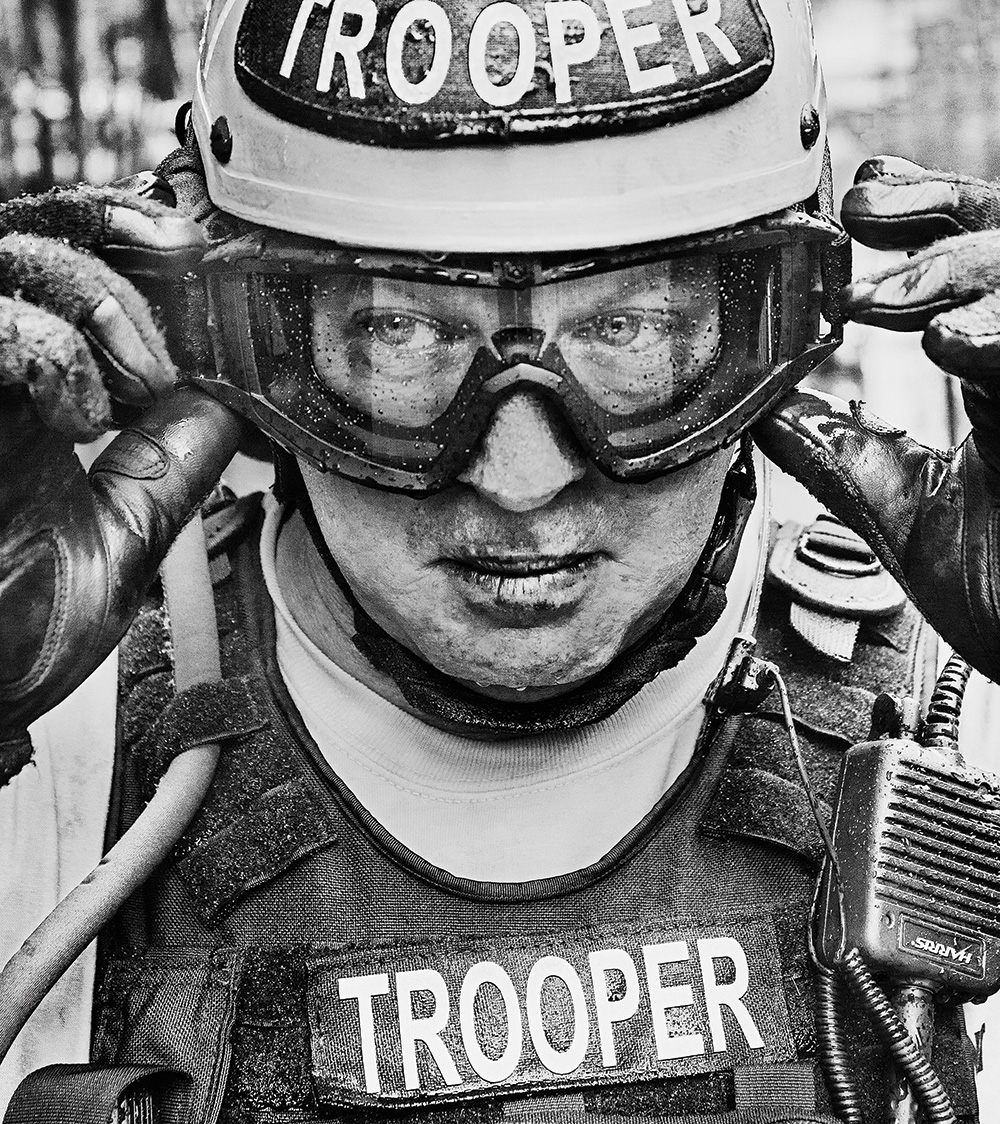

As the year 1990 came to an end, a fight broke out during a New Year’s Eve celebration at the Juke Box Saturday Night bar in downtown Minneapolis. A 21-year-old white student grabbed Michael Sauro from behind. Sauro, an off-duty white police officer working as a bouncer, handcuffed the man, dragged him to the kitchen, and then repeatedly drove his steel-toed paratrooper boots into his groin and head.

Sauro had been a cop for 15 years and had a long record of citizen complaints against him, most of them about excessive force. “I was dealing with animals,” he would later tell a reporter when asked about the people he’d beaten. “I mean, my dog is more human than them.” But he had never been disciplined. Four years after the bar fight, a court found that Sauro had used excessive force against the student, and it awarded $700,000 to him, then the largest civil award settlement in the city’s history. By then, Sauro had racked up 32 citizen complaints, though none had been sustained. The mayor finally fired him.

But his absence from the police department was short-lived. With the help of his union, the Police Officers’ Federation of Minneapolis, Sauro appealed to an arbitrator, who soon forced the city to rehire him with back pay. “These arbitrators always rule in favor of the police. It’s absolute and utter BS,” says Robert Bennett, an attorney who represented the victim and has sued the department dozens of times. A few months later, the police chief fired Sauro a second time for punching a Black student in the face near the Juke Box Saturday Night bar after the same New Year’s Eve party. Again, an arbitrator forced the department to rehire him. Then-Mayor Sharon Sayles Belton expressed her disappointment. “Allegations of abuse around Mike Sauro do not help create a climate of trust and respect,” she said.

Sauro was rehired in 1997 and stayed on the force for nearly two more decades. Eventually, his bosses put him in charge of the sex crimes unit, where women accused his team of failing to investigate some of their rape cases. In 2018, Amber Mansfield said he ignored her complaint that a man she knew had choked and raped her. “Sometimes victims have to take some responsibility for their decisions and their actions,” he told a reporter at the time. In 2019, after Sauro retired, an internal review found 1,700 untested rape kits at the department dating back to the 1990s. (Sauro disputes this finding.)

Three decades after Sauro beat the man at the bar, the Minneapolis police union is fighting to protect another set of officers accused of violence. On Memorial Day, Derek Chauvin knelt on the neck of George Floyd for nearly nine minutes, even after Floyd said he couldn’t breathe and went unconscious. Three officers who were with Chauvin never intervened. As Floyd’s death thrust the nation into protest, Mayor Jacob Frey described the city’s police union as a “nearly impenetrable barrier” to disciplining officers for racism and other misconduct, partly because of the legal protections it bargained for. “We do not have the ability to get rid of many of these officers that we know have done wrong in the past,” Frey told the podcast the Daily in June.

Police unions are at the center of questions about what will happen to Chauvin and the three officers who watched as Floyd was suffocated. And they are also key to understanding why officers across the country escape discipline time and again after beating or killing people. As other labor unions have shrunk in recent years, membership in police unions has remained high. While the Black Lives Matter movement encouraged people to document police brutality on camera and demand accountability, police unions, which now have hundreds of thousands of members, have pushed back in almost every way imaginable—by overturning firings, opposing the use of body cameras, and lobbying to keep their members’ disciplinary histories sealed.

All of which can make officers feel invincible when they commit acts of violence. A forthcoming research paper from the University of Victoria in Canada found that after police officers formed unions—generally between the 1950s and the 1980s—there was a “substantial” increase in police killings of Black and Brown people in the United States. Within a decade of gaining collective bargaining rights, officers killed an additional 60 to 70 civilians of all races per year collectively, compared with previous years, an increase that researchers say may be linked to officers’ belief that their unions would protect them from prosecution. A working paper from the University of Chicago found that complaints of violent misconduct by Florida sheriffs’ offices jumped 40 percent after deputies there won collective bargaining rights in 2003.

Police unions, like all unions, were designed to protect their own. But unlike other labor unions, they represent workers with the state-sanctioned power to use deadly force. And they have successfully bargained for more job security than what’s afforded to most workers, security they can often rely on even after committing acts of violence that would likely get anyone else fired or locked up.

And yet, in the broader push to reform the criminal justice system, police unions have remained largely untouchable, both by the broader labor movement, which has avoided criticizing their bargaining process, and by politicians on both sides of the aisle, who have accepted millions of dollars in campaign donations from them. Democrats don’t want to come down against unions, and Republicans, who are normally happy to attack unions, don’t want to mess with the police. When former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker destroyed collective bargaining rights for his state’s public sector unions in 2011, he left police unions mostly unscathed. The AFL-CIO, the country’s largest labor coalition, has referred to police unions as rightful beneficiaries in the movement for workers’ rights.

The uprisings of 2020 might have finally cracked the police unions’ invulnerability. As protesters demand justice for Black people killed by law enforcement, they are now calling to abolish police unions or drastically limit their power as part of a broader push to defund and demilitarize the police. This, in turn, may raise uncomfortable questions for the left about whether upholding civil rights and rooting out racism in law enforcement will require curtailing collective bargaining, and whether it’s possible to rein in cop unions without also hurting the broader labor movement.

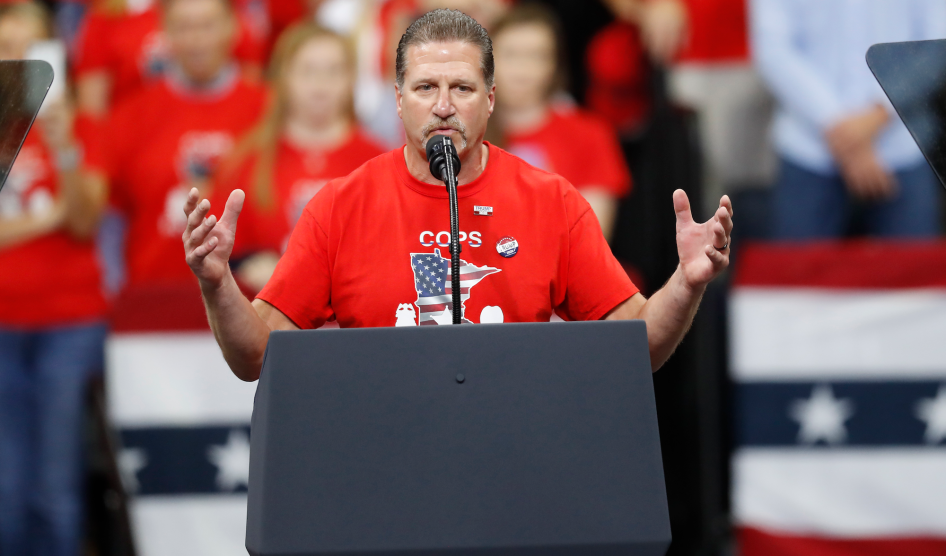

Minneapolis is now grappling with these questions. In June, City Council members said they intend to defund the police department and reenvision public safety in the city, a move they hope will defang the police union. But the Police Officers’ Federation of Minneapolis will not roll over without a fight. In the days following Floyd’s death, the union’s president, Bob Kroll, who is white, railed against the city’s politicians for not authorizing greater force to stop the protests, which he described as a “terrorist movement,” and which officers had dispersed with rubber bullets, tear gas, and flash grenades. Kroll also accused the police chief of firing Chauvin and the other officers “without due process,” and pledged to try to reinstate them. (Weeks later, he walked back that stance and said he did not believe Chauvin should be rehired.)

The union boss may feel emboldened by the White House. Last October, Kroll stood onstage with President Donald Trump at a campaign rally in Minneapolis and praised the “wonderful president” for “everything he’s done for law enforcement.” But some city lawmakers have had enough. Council member Jeremiah Ellison, whose father, state Attorney General Keith Ellison, is prosecuting the officers who arrested and killed Floyd, points out that Kroll is part of a biker club that allegedly displays white supremacist symbols. Yet he continues to enjoy support from the vast majority of the 800-plus officers in his union, who have elected him twice. “We’ve often sort of relegated Bob as a slight annoyance, and I think that was a mistake on our part,” Ellison says. “I think he’s a lot more dangerous than that.”

At a campaign rally last fall, Minneapolis police union boss, Bob Kroll, praised President Trump for “everything he’s done for law enforcement.”

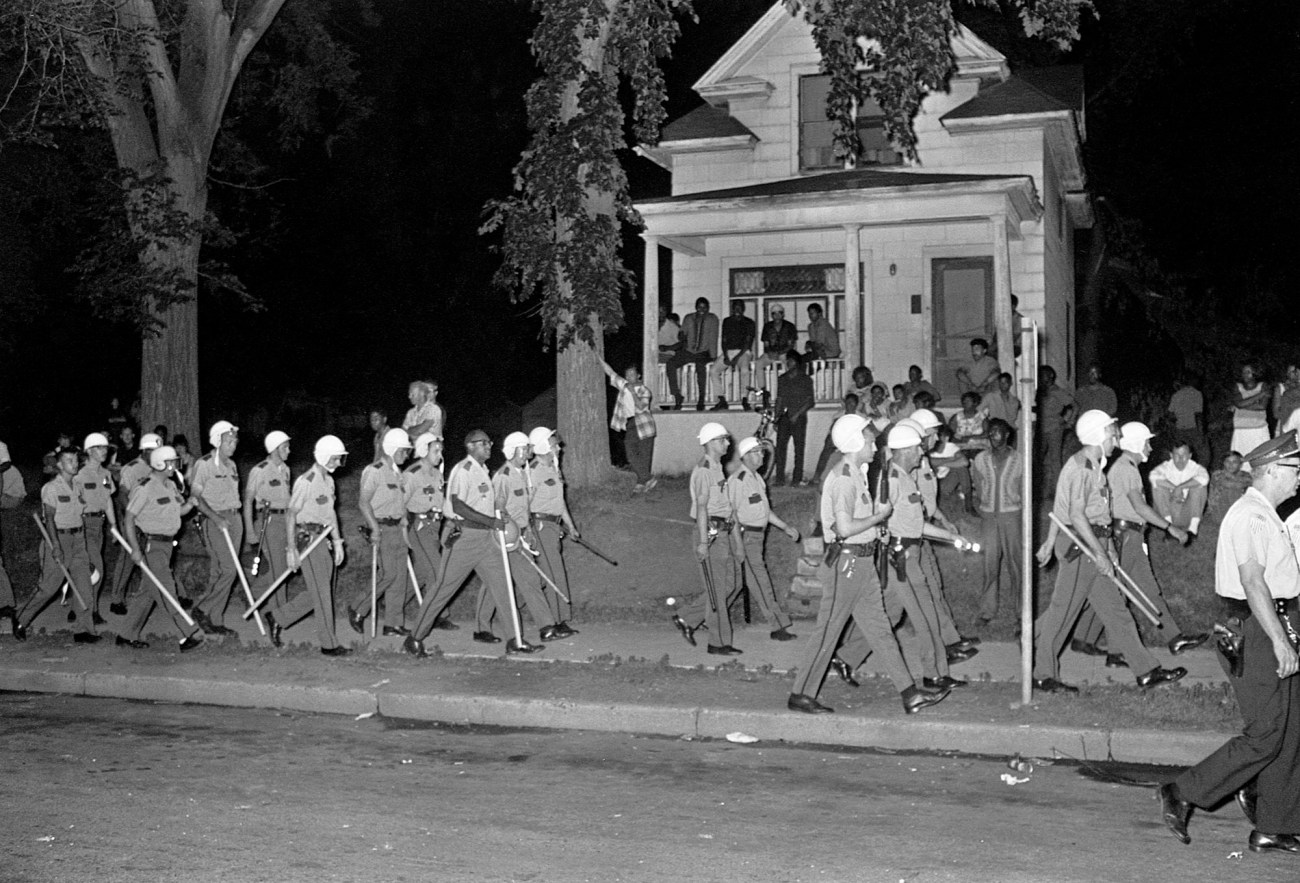

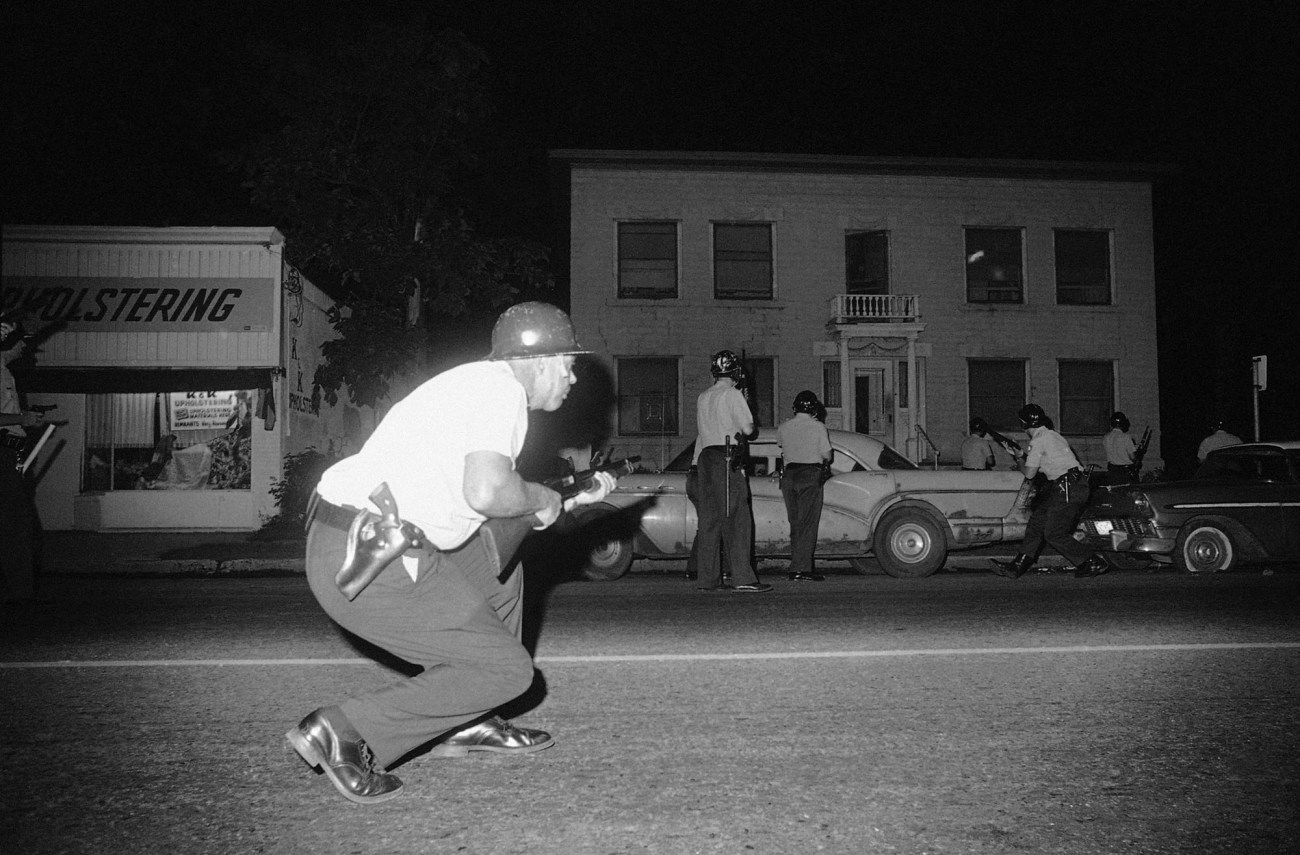

Stephen Maturen/Getty

Minneapolis has been here before, weighing police reform after massive, violent protests—and facing stiff resistance from the police union. In the summer of 1967, amid larger anti-racism protests around the country, there were several incendiary incidents in the city: That July, as witnesses recounted, Minneapolis police pulled a gun on a 5-year-old Black boy who wandered into the street during the annual Aquatennial parade. The cops called the boy the n-word and threatened to shoot him. Afterward, officers allowed white residents to hurl glass bottles at Black paradegoers as they walked home. Police stood by as white kids beat a Black boy on Plymouth Avenue on the city’s north side, where most Black residents lived. And they threw two Black girls to the pavement while breaking up a fight. Outraged, some people looted stores and set fire to shops along Plymouth. The violence escalated after a white bar owner shot a Black patron during an argument. Police officers and the National Guard were deployed to quell the uprising, as they were after George Floyd’s death in May.

Like Frey, the city’s mayor in 1967, Arthur Naftalin, proposed a series of police reforms. But he was no match for the Police Officers’ Federation of Minneapolis, according to Michael Lansing, a history professor at Augsburg University in Minneapolis who has studied the union’s political clout in the 1960s and ’70s. Like police unions around the country, the federation had seen its membership swell during the 1960s, partly in response to the civil rights movement, when police departments faced growing pressure to discipline officers for misconduct. Officers in many cities began to co-opt the language and strategies of the civil rights movement, and demanded a police bill of rights that would give them extra protections if they were investigated by their departments. For example, officers did not want to be questioned about misconduct without time to “cool off” and examine any testimony against them—privileges that are not afforded to suspects pulled in from the streets for interrogation.

Minnesota cops did not win a bill of rights until later. But when Naftalin urged the city’s police department to investigate citizen complaints, officers threatened a work “slowdown.” And when he tried to alter hiring procedures to bring more Black officers to the force, the police union’s president, a detective named Charles Stenvig, successfully opposed the change. Then in 1969, Stenvig campaigned to replace Naftalin as mayor by promising to “take the handcuffs off the police”—and won. In 1971, the police union pressured the City Council to prohibit the newly created Civil Rights Department from investigating officers for most citizen complaints. By the 1980s, when Democratic Mayor Donald Fraser appointed a reformist police chief to curb violence within the department, the union opposed his every move. In an editorial, the Minneapolis Star Tribune openly questioned “whether the mayor and the council will control the police department, or whether the power will shift to the police union.”

The answer became clearer as the war on drugs escalated and the police became more militarized. In 1989, Michael Sauro, the officer who would later be fired and rehired, led a botched no-knock drug raid on the home of an elderly Black couple who were killed in their bed after a SWAT officer threw a grenade through a window, setting their living room on fire. All the officers were cleared of wrongdoing. Keith Ellison, then a law school student, led protests demanding accountability, and the city established a civilian review board that could investigate officers accused of misconduct. But the board had little power, in part because of the union. Over the next two decades, allegations of police abuse mounted: Officers kidnapped an African man to extort $300 from him; shoved two Native men, who’d passed out, into the trunk of a squad car; and shot a 19-year-old Hmong man after chasing him near a school. The police union, facing pressure to reform, instead lobbied the state legislature in 2012 to prohibit the civilian review board from issuing statements about whether officers had committed misconduct.

When Kroll became the union’s president in 2015, he and Sauro were “birds of a feather,” says attorney Bennett. Kroll fervently opposed the Black Lives Matter movement, which had gained momentum after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Not long after Kroll’s election, two white officers in Minneapolis killed 24-year-old Jamar Clark after they said he’d reached for one of their guns during an arrest, igniting protests across the city. Kroll accused Clark of having a violent criminal history. When a federal investigation cleared the officers of wrongdoing, he referred to Black Lives Matter as a “terrorist organization.”

Kroll had “a history of discriminatory attitudes and conduct,” according to a 2007 lawsuit alleging racism in the police department, filed by officers including then-Lieutenant Medaria Arradondo, who is Black and now the city’s chief of police. In 2007, colleagues accused Kroll of insinuating that Keith Ellison, who had just become the first Muslim elected to Congress, was a “terrorist.” (Kroll denies the allegation.) The lawsuit also accused Kroll of wearing a motorcycle jacket with a “‘White Power’ patch.” In June, Kroll was made to address that allegation too. He denied it but said he’s a member of the City Heat motorcycle club, some of whose members have been accused of displaying white supremacist symbols. He did not respond to questions from Mother Jones.

As head of the union, he advocated aggressive policing. Under former police Chief Janeé Harteau, he opposed policies requiring officers to intervene if they saw a colleague use excessive force. (Kroll was disciplined at least three times and was suspended from the force—until a successful appeal—for beating up a man while off duty in 2004; he reportedly lost a chunk of his ear in another off-duty fight.) He also pushed back last year when Mayor Frey banned “warrior-style” trainings that were linked to other shootings by officers, including of Philando Castile just outside Minneapolis in 2016. The trainings espoused a “killology” view of policing that urged officers to be prepared to use more force, not less. Kroll called the ban illegal and vowed to make the trainings free for union members. “It’s not about killing, it’s about surviving,” he told the Star Tribune. He reiterated this sentiment in a radio interview in April: “Certainly getting shot at and shooting people takes a different toll, but if you’re in this job and you’ve seen too much blood and gore and dead people, then you’ve signed up for the wrong job.”

That attitude makes the police union seem more like a warrior cult than a labor union, says longtime Minneapolis organizer Ricardo Levins Morales, who’s part of MPD150, a collective of activists who studied the union’s history. It’s “just one of the layers of smugness that you see on officers’ faces when they are committing a crime and know nothing is going to happen to them. They have the ultimate power.”

Shortly after Floyd’s killing, Kroll sent a letter to his union members in which he defended Chauvin and the other officers at the scene, saying they were unfairly disciplined. By late June, he’d changed his stance on Chauvin and said he no longer considered Black Lives Matter a terrorist organization, but he still believed protesters in Minneapolis engaged in “domestic terrorist activities.”

And Kroll mostly stood by the three officers who did not intervene in Floyd’s death, saying the union could not condemn them without seeing more evidence. He also disputed the mayor’s claims that he opposed reforms. The union, he told CBS’s Gayle King, was being “scapegoated by political leaders in our city and our state, and they have shifted their incompetent leadership, failed leadership, onto us and our members, and it is simply unjust.”

“We’re willing to sit down and talk about any reforms brought to us,” Kroll told local CBS affiliate WCCO, where his wife works as a reporter and covered public safety without disclosing their relationship to viewers for some time.

Rich Walker Sr., a union board member who joined Kroll for that interview, and who is Black, denied that the police department is racist, and said people shouldn’t blame the union for the unrest. “We never rejected reforms,” he said. “We accept no responsibility of what’s going on in our city.”

Kroll may seem extreme, but among police union leaders, he’s not that much of an outlier. Almost any time a police officer’s use of excessive force has made national news, you can bet that police unions were pushing back against the protests and calls for change. When Daniel Pantaleo, the New York City officer who choked Eric Garner while arresting him for allegedly selling untaxed cigarettes in 2014, was finally fired in 2019, the police union appealed that decision and threatened a work slowdown. When one of the officers involved in the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore was acquitted of murder in 2016, the union there posted a magazine cover on its Twitter account that referred to local prosecutor Marilyn Mosby, a Black woman, as “The Wolf That Lurks.” In Cleveland, the Police Patrolmen’s Association is still trying to overturn the firing of the white officer who killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice six years ago. And even when their members aren’t being directly criticized, local unions push back: When San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem in 2016 to protest police brutality, the Santa Clara police union said its officers might stop providing security at home games.

No matter how diverse or progressive a city’s leaders are, police unions offer a formidable counterweight. And they are almost exclusively led by white men. That helps explain why these union members are so often caught making racist comments. Kim Gardner, the first Black person to work as lead prosecutor in St. Louis, sued the union there for a culture of racism; the union chief had referred to her as a “menace to society” who must be removed “by force” if necessary. In Kroll’s interview with Gayle King, he denied that the Minneapolis Police Department struggled with systemic racism, even after officers were fired for putting up a Christmas tree at work that was decorated with racist tropes like an empty Popeyes cup and menthol cigarettes. (The union appealed their firing.)

But it’s not just racist bark—unions have bite, thanks to protections they’ve won through collective bargaining. “Police unions have gotten in their contracts all sorts of provisions which make it difficult to investigate and find officers guilty of misconduct,” says Samuel Walker, a researcher on police unions and an emeritus professor at the University of Nebraska, Omaha.

In at least 50 cities, according to a 2017 Duke Law Journal article, union contracts require police departments to wait a significant period of time, normally at least 48 hours, before interviewing an officer for misconduct, providing the officer with ample time to come up with a justification for their behavior, align their story with those of colleagues, or speak with a lawyer. In at least 34 cities, departments must show officers all the evidence against them before the questioning. And in dozens of cities, contracts require police departments to destroy or seal officers’ disciplinary records after a certain period of time, sometimes as little as two years after the offense. Other contracts prevent investigators from considering an officer’s past misconduct in disciplinary proceedings, and some shield disciplinary records from public view altogether. “It’s a huge issue for accountability,” says Samuel Sinyangwe, a data scientist with Campaign Zero who studies police unions. If officers’ histories are systematically purged, he says, it’s hard to identify those who repeatedly engage in misconduct, let alone remove them from the force.

Police patrol Plymouth Avenue in Minneapolis during anti-racism protests in July 1967.

Minnesota Historical Society/Corbis/Getty

In the event that a cop is fired, union contracts and state law often guarantee they can appeal their firing to independent arbitrators, who can reinstate them in their jobs with back pay. That’s how Sauro stayed on the force. It’s also how Hector Jimenez, an Oakland officer who shot two unarmed men in the mid-2000s, got rehired. Officers have been reinstated after facing domestic violence allegations, accidentally shooting someone while drunk, and saying racial slurs. Last year, an arbitrator sided with a University of Minnesota cop, a member of the Law Enforcement Labor Services union, who was accused of grabbing a woman by the neck while he was off duty. He denied the allegation, though her collarbone was bruised, and he admitted to getting into her personal space during an argument. “It’s an emotional issue among police chiefs. To do the hard work of firing an officer and then have the arbitrator hand them back to you, it’s infuriating,” says Walker, the researcher. Minneapolis police Chief Arradondo echoed that sentiment at a press briefing in June: “There is nothing more debilitating to a chief, from an employment matter perspective,” than being unable to fire an officer for misconduct.

Arbitrators aren’t elected officials; they’re usually attorneys who are mutually selected by the union and city officials, with broad discretion to decide whether an officer was disciplined fairly. They often side with cops because they rely on precedent—a big problem when you consider that police departments have a long history of allowing officers to get away with violence. In the case of the cops responsible for Floyd’s death, an arbitrator might look back to 2010, when two white Minneapolis police officers restrained a Black man named David Cornelius Smith for four minutes by sitting on his legs and putting a knee to his back, even after he stopped breathing. Smith died of asphyxia, and the officers were never disciplined.

In Louisville, Kentucky, where police shot Breonna Taylor eight times in her home during a drug raid that found no drugs, the city’s mayor warned that disciplining the responsible officers would likely be a drawn-out process because of an agreement with the union. As of mid-July, only one of the three officers who shot their weapons was fired—and, with help from his union, he was appealing.

When cops overturn their firings, it can embolden them. Sauro is a case in point. In 2009, more than a decade after he was rehired, he sent an email to colleagues outlining his philosophy on using violence during patrol. In the email, Sauro, previously a board member of the union, argued that Minneapolis officers had acted appropriately when they kicked and punched a Black man lying on the ground after they pulled him over for driving 15 mph over the speed limit. He added that civilians had themselves to blame if they were harmed by police. “If the suspect does not produce his driver’s license when requested he than [sic] dictates that force be used, not the officer,” Sauro wrote. Then, perhaps remembering his own bar fight, he added in all-caps—twice—that “in my 35 years as a Minneapolis police officer there is not one documented case of a suspect dying from a blow to the head by a Minneapolis police officer.”

Mayors and other elected city officials don’t have to bargain away so much power to police unions, but again and again they do. That may be because unions have a lot of political clout, with big membership bases that account for the vast majority of officers in large cities. While other labor movements have shrunk since the 1970s, the Fraternal Order of Police, one of the country’s biggest police unions, had 341,946 members at the end of 2018, its most in almost a decade. Police officers and their unions spent at least $47 million at the federal level on campaign contributions and lobbying in recent election cycles, according to an investigation by the Guardian.

Unions can give hell to mayors who oppose their agenda, particularly by attacking them as soft on crime or threatening a sick-out. They also flex in other ways against politicians who don’t get in line. In May, the head of the New York City sergeants’ union disclosed personal information on Twitter about Mayor Bill de Blasio’s daughter after she was arrested during anti-police protests. In Minneapolis, when City Council member Steve Fletcher backed a budget that diverted $1 million from police to other public safety measures, business owners in his district reported that cops took longer to respond to their 911 calls about shoplifting. “When they came, they said, ‘We would love to help you, but talk to your Council member about why we didn’t have more officers on this shift,’” Fletcher recalls his constituents reporting. Ralph Remington, a former City Council member in Minneapolis, says Kroll and three other union members threatened him in 2006 after he pushed for police reforms. At a meeting at a coffee shop, Remington told reporters at the time, the men raised their voices and vowed not to endorse him if he didn’t cooperate, a warning that Remington said felt like a physical threat.

Police unions spend heavily to beat candidates they don’t support. The San Francisco Police Officers Association and its allies doled out $700,000 in a failed effort to oppose Chesa Boudin, a former public defender who was elected as district attorney in 2019 after promising sweeping criminal justice reform. The union bought campaign ads describing him as the “No. 1 choice of criminals and gang members,” and later created a website called BoudinBlunders.com, where people could submit tips aimed at smearing him. In Los Angeles, the LA Police Protective League donated $1 million trying to defeat reform-minded district attorney candidate George Gascón in the March primary. His opponent, incumbent Jackie Lacey, was criticized by Black Lives Matter for only charging two out of the hundreds of law enforcement officers in the county who killed someone since she was elected. Meanwhile, all but two California lawmakers received campaign donations from police unions and associations between 2011 and 2017, according to a study by Sinyangwe. Unions gave more heavily to Democrats who opposed police reform bills, in a state where police kill more people than anywhere else. In 2017 alone, they spent $2 million to influence legislation in California, nine times more than even the NRA doled out for lobbying in the state.

The political clout of police unions extends to Washington. Though former Vice President Joe Biden is now pushing for law enforcement reform as part of his presidential bid, he worked closely with police unions while authoring the 1994 crime bill in the Senate, which provided funds to hire 100,000 more officers. “There wasn’t one thing when he said, ‘No,’” Tom Scotto, then president of the National Association of Police Organizations, which represents 240,000 officers, said in an interview with the Washington Post. “We would not be here were it not for the police helping fashion this bill,” Biden said at the time.

Trump, meanwhile, is every police union boss’s dream. In June, after threatening to deploy the military against anti-police protesters, he unveiled a tepid proposal to improve police training and track misconduct. He did so at a Rose Garden ceremony surrounded by police union officials; no family members of Black people who had been killed by police were present. “I strongly oppose the radical and dangerous efforts to defend [sic], dismantle, and dissolve our police departments,” he declared. “Americans want law and order. They demand law and order,” he added. “They may not say it, they may not be talking about it, but that’s what they want.”

In the wake of Floyd’s death, some politicians are taking steps to sever their ties with police unions. By early July, more than a dozen House Democrats signed a pledge to reject campaign contributions from the Fraternal Order of Police, including representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts, and Rashida Tlaib of Michigan. And in May, more than 40 district attorneys wrote that prosecutors “should not seek or accept” support from police or their unions. But that leaves more than 2,000 head prosecutors who did not sign on.

There’s also growing pressure to kick cop unions out of labor councils like the AFL-CIO, the country’s biggest union coalition. Police unions are different from other unions anyway, since they’ve never been aligned with the larger labor movement and have often acted as adversaries. In Minneapolis in the early 1900s, the police department regularly broke up strikes after forming an alliance with a right-wing business group known as the Citizens Alliance. In 1968, Memphis police responded to a Martin Luther King Jr.–led march in support of striking sanitation workers by macing and clubbing demonstrators who had taken refuge in a church. “The police have a history of cracking heads on picket lines, and yet anytime you try to lean into a reform, they recede into this labor solidarity movement that they’ve never been a part of,” says Jeremiah Ellison, the Minneapolis Council member.

After the Police Officers’ Federation of Minneapolis formed in 1916, the Alliance pressured union members to sever ties with the American Federation of Labor, and it has remained independent from the labor movement since. But some other unions haven’t. The AFL-CIO is affiliated with the International Union of Police Associations and a dozen other unions that include law enforcement as members. Historically, leaders of the country’s biggest union coalition have refrained from bad-mouthing police unions, even while condemning police violence. When Officer Darren Wilson shot Michael Brown in Ferguson, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka expressed remorse but referred to the officer as family. “Lesley McSpadden, Michael Brown’s mother, who works in a grocery store, is our sister, and an AFL-CIO union member, and Darren Wilson, the officer who killed Michael Brown, is a union member, too, and he is our brother,” Trumka said. “Our brother killed our sister’s son and we do not have to wait for the judgment of prosecutors or courts to tell us how terrible that very thing is.” When the Center for Public Integrity reached out to 10 major unions and labor groups following George Floyd’s death, including the AFL-CIO, none were willing to have a conversation about police unions.

Protesters have noticed. In June, people set fire to AFL-CIO headquarters and smashed its windows during anti-police demonstrations near the White House. It is unclear if the building was targeted because of the coalition’s ties to police unions. Afterward, when its boarded-up windows were plastered with posters that read, “AFL-CIO Supports Black Lives Matter,” someone put up another sign on the building: “Hey AFL-CIO,” it read, “The Posters Are Nice, But If You Believed It You Would kick the police unions out.”

The AFL-CIO isn’t budging. In a statement after the protest, the group condemned Floyd’s death and urged Kroll to resign from the Minneapolis union, but said it would not cut ties with the International Union of Police Associations. “First and foremost, we believe police officers, and everyone who works for a living, have the right to collective bargaining,” it said. “There are officers of every color, background and stripe in America.”

Yet just below the national leadership, the ground has started to shift. In June, MLK Labor, which represents more than 100,000 workers in Washington’s King County and is affiliated with the AFL-CIO, voted to expel the Seattle Police Officers Guild from its labor council. In August, the California Labor Federation, which is part of the AFL-CIO and represents 2.1 million workers, passed a resolution to dissociate from police unions and defund law enforcement. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union staged protests against police on Juneteenth, shutting down major ports all along the West Coast. In Oakland, California, members of engineer and service worker unions lobbied City Hall for substantial cuts to the city’s law enforcement budget. Across the country, millions of other union members have joined protests to make similar demands.

For some activists, simply expelling law enforcement from labor councils isn’t enough. In a recent op-ed, Michael McQuarrie, director of the Center for Work and Democracy at Arizona State University, pointed out that state legislatures could eliminate police unions, since public sector unions are governed by state laws. But Walker, the researcher at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, pushes back on the feasibility of this approach, arguing that while officers have abused union power to shield themselves from discipline, they do have a legal right, like other public workers, to bargain for better working conditions. McQuarrie suggests that abolishing these unions might also threaten the collective bargaining rights of teachers, nurses, bus drivers, and other public sector employees.

Reforming the police’s collective bargaining does not necessarily have to upend the rights of other workers. In an op-ed, Benjamin Sachs, a Harvard labor law expert, wrote that courts, including the Supreme Court, have stepped in to limit specific types of bargaining powers without threatening unions more generally. Lawmakers could limit the types of subjects that cops can bargain over—for instance, allowing them to negotiate their pay and benefits, but not disciplinary procedures. In June, the Washington, DC, Council voted to do just that. It’s “a best practice that other cities should look to,” says Sinyangwe, the data scientist.

A policeman crouches in the middle of Plymouth Avenue in Minneapolis in July 1967.

Robert Walsh/AP

In Minneapolis, the police chief and mayor have called on the state legislature to revise the law that governs the union arbitration process. California and New York lawmakers, meanwhile, have changed laws that had shielded police disciplinary records. New York City’s Police Benevolent Association spent at least $1.8 million on state and local campaign contributions and lobbying fees during the five years it fought to keep the documents secret. Since 2019, journalists have used expanded access to California police records to write more than 100 articles on abuses of power, false arrests, and officers who were fired for misconduct and then rehired by other agencies.

It may also be possible to defang cop unions by returning to the main demands of Black organizers: Defund and dismantle the police. Reducing the size of the force, says Theresa Rocha Beardall, a sociologist who studies police unions at Virginia Tech, can do a lot to reduce the power of its union. “As you grow, your union dues increase, and as your union dues increase, so does your leverage over city hall,” she says. Cut membership, and mayors may take a harder line during negotiations.

That’s what Minneapolis City Council members are trying to do. While completely defunding and dismantling the police will likely require a public vote, which will not happen before 2021, Ellison says Council members are determined to reimagine public safety—to invest more in social services that prevent crime in the first place, and to consider whether other trained professionals, like social workers, might respond better to certain 911 calls. “Hopefully we’re moving in a direction where we no longer have to deal with this bargaining unit,” Ellison says of the police union. When asked in June whether he envisioned scrapping the city’s contract by firing all the officers, Ellison only said the Council was weighing its options. “Look, we are entering into, as far as the country is concerned, uncharted territory,” he told reporters.

It may well be that George Floyd’s death and the uprising that followed marked a turning point. The protests of 2020 are already far bigger than those that gripped Minneapolis in 1967. They’ve spread to cities across the country and around the world, creating space for people to imagine an alternative to the status quo of cops writing their own rules for accountability. “The police union is an entity that can be created,” says Michael Lansing, the historian in Minneapolis. “And anything that can be created can be uncreated.”