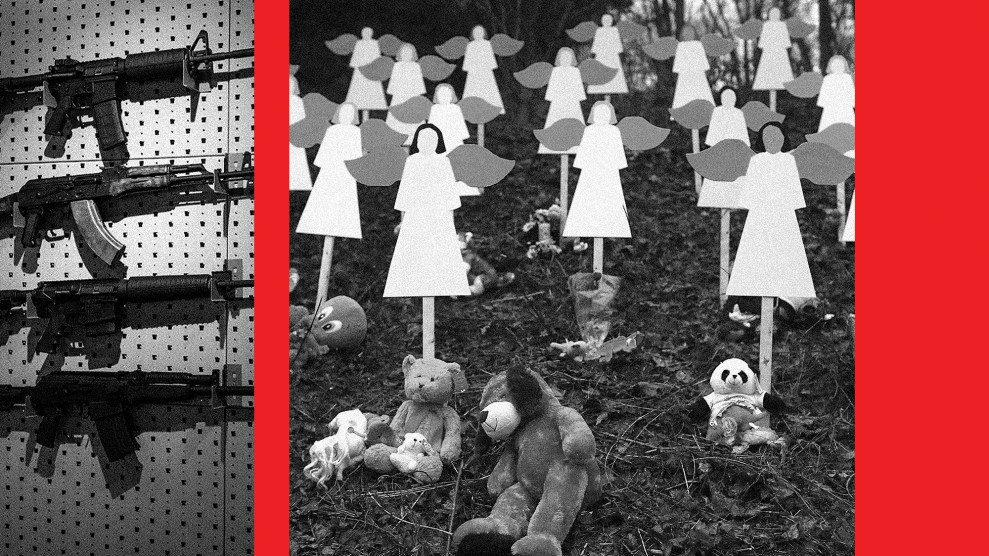

Getty; Spencer Platt/Getty

On a cold December morning a decade ago, a suicidal 20-year-old male used an AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle to murder 20 first graders and six educators at Sandy Hook Elementary School. The devastation for the victims’ families and the community of Newtown was nearly indescribable. Grief and outrage gripped the nation. The US president wept openly. Tributes from around the world deluged the small Connecticut town. Four months later, Congress infamously failed to muster any legislative response. A new era of gun safety activism soon caught fire through social media. Pro-gun extremists viciously targeted the women leading it. An American epidemic of mass shootings was on the rise.

The events of December 14, 2012, had a profound effect on many people, including me. Investigating and writing about gun violence—work I’d begun five months earlier after an unprecedented massacre at a movie theater in Colorado—would become my prime journalistic pursuit for the next decade. About a year into creating and then frequently expanding our Mother Jones database of mass shootings, I began to learn about behavioral threat assessment, a field of violence prevention virtually unknown at the time to the general public. Its collaborative method of intervention used by experts in mental health, law enforcement, education, and other relevant professions would later become the focus of my book Trigger Points.

After years of research into the origins and emerging work of threat assessment—which likely has prevented dozens, if not hundreds, of violent attacks throughout the country—I came to see that we could do far more as a society to reduce mass shootings. Now, a decade after Sandy Hook, a spate of gun massacres in 2022—including another nightmare at an elementary school—has only further clarified how America can and should think more broadly about confronting this distressing problem, which remains a fraction of the overall gun violence epidemic but inflicts outsize impact.

Longterm efforts to improve gun regulations in ways that a bipartisan majority of Americans support will remain vital. But progress also means contending with the reality that we are a country with an estimated 400 million firearms, which are easy to acquire in many places and include millions of rifles designed originally for use in war. This status quo is unlikely to change broadly anytime soon.

Such progress begins with rejecting the longstanding narrative that mass shootings are inevitable and will never cease, a theme reliably delivered after each horrific tragedy with the political cri de coeur that “nothing ever changes.” As I wrote after the disaster at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, it’s about more than just moving beyond the entrenched polarization and despair of our national deadlock on gun politics, which finally began to crack with federal legislation passed in June. The assertion that mass shootings are an inherent feature of our reality is in its own right fueling the problem, in part by validating this form of violence in the eyes of its perpetrators, who seek justification and notoriety for their actions. Case evidence reveals this effect explicitly.

What the carnage of 2022 shows in vivid terms is how two specific areas of policy could take us far in confronting the mass shootings scourge. First, we need to shift away from the heavy overemphasis on active shooter response—lockdown drills and the various “target hardening” measures of physical security—to a greater emphasis on active shooter prevention. This means investing in mental health care and community-based violence prevention, including behavioral threat assessment programs, which can have a broader benefit of helping foster a climate of safety and well-being, from corporate and college campuses to K-12 classrooms. That may now be particularly valuable in an era when a majority of parents nationwide express fear about sending their children off to school.

Additionally, two types of gun regulations hold significant promise for helping reduce mass shootings in America. One is raising the age requirement for gun buyers from 18 to 21. Another is expanding the use of extreme risk protection orders, a policy known as red flag laws, for temporarily disarming individuals deemed through a civil court process to pose a danger to themselves or others.

Five devastating gun massacres since last May point directly to the value of these solutions. All five attacks—in Buffalo, New York; Uvalde, Texas; Highland Park, Illinois; Colorado Springs; and at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville—were carried out by deeply troubled and aggrieved young offenders, ages 18 to 22, who fit behavioral patterns known to threat experts. All showed various combinations of warning signs ahead of time. Those included aggression and other behavioral and mental health troubles; observable deterioration in life circumstances; various forms of communicated threats; focus on graphic violence, misogyny, and ideological extremism; and planning and preparation for the attacks.

Taken together, the picture of these five mass shootings is especially telling in terms of the weapons and tactical gear involved:

May 14: Tops supermarket; Buffalo, New York

Perpetrator: 18-year-old male

Weapons and gear: AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle, large-capacity ammo devices; wore body armor and a tactical helmet with a camera

May 24: Robb Elementary School; Uvalde, Texas

Perpetrator: 18-year-old male

Weapons and gear: AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle, large-capacity ammo devices; wore a tactical vest; had purchased other gear including a holographic gun sight and a “Hellfire Gen 2” snap-on trigger system

July 4: Independence Day parade; Highland Park, Illinois

Perpetrator: 21-year-old male

Weapons and gear: AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle, large-capacity ammo devices; posted photos of himself prior to the shooting wearing a tactical helmet with a camera

Nov. 13: University of Virginia campus; Charlottesville

Perpetrator: 22-year-old male

Weapons and gear: semiautomatic pistol; an arsenal found in his dorm room included an AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle, large-capacity ammo devices, and a federally legal “binary trigger” device enabling a more rapid rate of firing

Nov. 19: Club Q nightclub; Colorado Springs

Perpetrator: 22-year-old (defendant’s attorneys say defendant identifies as nonbinary)

Weapons and gear: AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle, semiautomatic pistol, and large-capacity ammo devices; wore body armor

Threat assessment research shows that many mass shooters fixate on military-style weapons and gear and identify with a “commando” mentality. The problem has grown against a backdrop of gun manufacturers aggressively marketing semiautomatic rifles as emblematic of military and masculine prowess, including through product placement in movies and video games popular with young males. The type of “Bushmaster” rifle wielded by the Sandy Hook shooter had been billed as a means for buyers to get their “man card” in advertising from its maker, Remington, which agreed early this year to a landmark $73 million civil settlement with victims’ families. The family of a 10-year-old victim in Uvalde filed suit in November against Daniel Defense, the maker of the rifle used at Robb Elementary, alleging the company used militaristic marketing appeals to target “young male consumers.” (Additionally, an NRA commentator made a glossy promotional video not long after Sandy Hook that likened a Daniel Defense assault rifle to a sexy young woman, as I documented in this 2014 story.)

Historically, semiautomatic pistols are the top weapon of choice for mass shooters, but the past decade brought a sharp increase in shooters using military-style semiautomatic rifles. Among the 83 mass shootings since 2012 documented in the Mother Jones database (whose perpetrators also include several high school adolescents and various middle-age men), 34 of the cases involved such assault rifles.

As those weapons have soared in popularity in the United States, there also remains scant regulation of the military-grade body armor that mass shooters increasingly use. Such gear helped protect the perpetrator who committed the racist mass murder at the supermarket in Buffalo; his body armor stopped a bullet fired by a security guard, whom he then fatally shot. Body armor also made it more difficult to stop the attacker at Club Q in Colorado Springs, according to the military veteran who heroically took him down.

With the Uvalde massacre, scrutiny of the catastrophic response by law enforcement remains the overwhelming media focus, arguably at the expense of public awareness about other painful and sobering aspects of the case. Among them is the array of missed warning signs from the suicidal perpetrator that included animal cruelty, online threats, a focus on violent misogyny, and other starkly aberrant behaviors.

The lesser known case details also include the sheer firepower he purchased immediately after turning 18. The arsenal he acquired just days ahead of his attack—which contained multiple guns, tactical gear, and large quantities of highly lethal ammunition—drew relatively little media attention but was detailed deep into an investigative report from the Texas legislature, as I highlighted in July:

An online retailer shipped 1,740 rounds of 5.56mm 75-grain boat tail hollow point to his doorstep, at a cost of $1,761.50. He ordered a Daniel Defense DDM4 V7 (an AR-15-style rifle) for shipment to a gun store in Uvalde, at a cost of $2,054.28. On May 17, 2022, he bought a Smith and Wesson M&P15 (also an AR-15-style rifle) at the same store in Uvalde, at a cost of $1,081.42. He returned the next day for 375 rounds of M193, a 5.56mm 55-grain round with a full metal jacket, which has a soft core surrounded by a harder metal. He returned again to pick up his other rifle when it arrived on May 20, 2022, and he had store staff install the holographic sight on it after the transfer was completed.

Four days later, two teachers and 19 schoolchildren were dead.

The cluster of cases this year is an escalation of a trend. Last year, the 21-year-old who struck at a supermarket in Boulder, Colorado, used an AR-15-style rifle and wore a tactical vest. Three cases in 2019—at a festival in Gilroy, California; a Walmart in El Paso, Texas; and on the streets of a nightlife district in Dayton, Ohio—involved young men using semiautomatic assault rifles and various tactical gear. The prior year, the 19-year-old who attacked Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, used an AR-15 and wore tactical gear. The year before that, a 26-year-old committed a massacre at a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, using such weapons and gear. Dating back a decade, the 24-year-old gunman who opened fire with a semiautomatic rifle in the Colorado movie theater in July 2012 was outfitted from head to toe in body armor. And that December, the 20-year-old Sandy Hook shooter, who had studied the actions of numerous predecessors, wore earplugs and a utility vest as he used the Bushmaster rifle to carry out his slaughter.

The politics that stand in the way of change are vexing to say the least. The specific policy solutions are no longer theoretical. Leading research in California published in June indicated that use of the state’s red flag law may have helped prevent dozens of mass shootings over a three-year period beginning in 2016. Now on the books in at least 19 states and the District of Columbia, these laws have also been shown effective for preventing suicide, which is the endgame for a majority of mass shooters.

Yet, while funding to boost red flag laws nationally made it into the gun safety legislation passed by Congress in June, many Republican officials remain hostile to the policy. That’s despite it being designed to keep guns out of the hands of dangerous people, precisely as those same Republicans call for after every major mass shooting.

In the case of the Club Q massacre, disturbing questions loom as to why Colorado’s red flag law was not used to disarm the perpetrator in 2021, after the suspect was arrested for provoking a bomb scare and engaging in a heavily armed standoff with law enforcement. For reasons unknown to the public, the five felony charges were dropped in that case, whose context includes a threat by the perpetrator to become “the next mass killer,” and a sheriff presiding in a “Second Amendment sanctuary” county who has stated in general terms that he would not seek to use the red flag provision.

Moreover, efforts to raise the legal age for buyers of assault rifles from 18 to 21 were opposed by many Republicans, including—only a month after Uvalde—by the two US senators from Texas. Such a law could have potentially kept AR-15s away from the perpetrators in Uvalde, Buffalo, Gilroy, and Parkland, all of whom used guns obtained legally.

A case in Seattle freshly illustrates the potential for preventing mass shootings, both in terms of these specific gun regulations and threat assessment work. In mid-November, a King County judge used Washington’s red flag law to bar a potentially dangerous 18-year-old high school student from possessing firearms. According to court testimony reported by Seattle’s KUOW, local police investigated after the student had asked a friend to help him acquire an assault rifle and told a therapist about his desire to commit a mass shooting at a high school he’d previously attended, after which the therapist notified police.

The troubled student said he’d been bullied and confessed that he had a history of thinking about conducting mass killings. Notably important from a threat assessment perspective, he further stated to police that he “realized he didn’t need to specifically target those who had bullied him,” but that he instead felt he could indiscriminately kill “a multitude of students” at his former high school to cause pain and anguish for those against whom he wanted revenge.

That shift in focus by a would-be shooter to a broader group of potential victims—known to experts as “target dispersion”—signals increased danger for an attack.

The subject of the threat case, whom KUOW did not identify because he had not been charged with a crime, reportedly made another noteworthy statement to police. It underscores the despairing ambivalence that many young perpetrators of mass shootings feel in the runup to their attacks, and it further suggests the promise for expanding prevention policies nationally.

When the student was served with the extreme risk protection order in mid-November, he acknowledged the intent of the gun prohibition, according to testimony from a police officer who was present. “This is really helpful to know,” the young man said in response, “that I couldn’t get anything even if I wanted to.”