Justin Sullivan/Getty

On the morning of June 22, as the coronavirus was spreading through the dormitories and cells of San Quentin State Prison, a prisoner I’ll call Gabe picked up a blue pen and a half-finished letter he had put down the night before. Elsewhere in his cell block, prison staff were escorting a sick prisoner away. “As I sit in this cell and hear another person go out [because] they are having trouble breathing I cannot help but contemplate my own death,” he wrote to his partner, Jordan, who requested I use pseudonyms for them both out of fear that Gabe could face retaliation. “I think, what if that was me going out?”

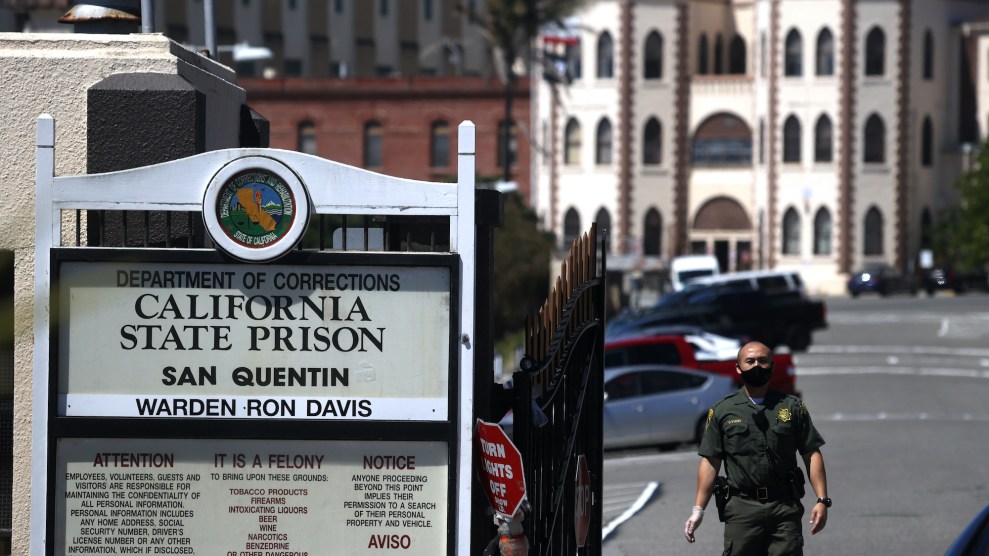

San Quentin is currently the site of one of country’s worst COVID-19 clusters, with 1,300 prisoners and 184 staff having tested positive for the coronavirus as of July 7. At least six prisoners have died from the virus. Sick prisoners are being put in isolation or treated in tents, while those who have not fallen ill are locked down in crowded dormitories and cell blocks where fear of the coronavirus is sometimes overwhelming. Gabe, who has spent about 25 years inside, including several in solitary confinement, told Jordan the lockdown was the hardest time he had ever done. In his letters, he describes being locked in his cell for more than 23 hours a day, unable to go out on the yard, with limited access to showers and programs. “I began to feel hopeless the more helpless I become,” he wrote on June 25. “We sit and wait, wait for what? That is the anxiety.”

On May 30, the prison of about 3,500 people on the edge of San Francisco Bay had zero coronavirus cases. Then California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) officials transferred 121 people to San Quentin from the California Institution for Men in Chino, which was struggling with a fierce outbreak. Some of the men, who had medical risk factors and hadn’t been tested for up to four weeks, were packed onto buses where a handful fell ill even before they arrived at San Quentin. There, they were placed in a housing unit called Badger, where tiers of cells opened onto a shared atrium, according to a San Francisco Chronicle investigation.

The virus spread swiftly in the overcrowded, poorly ventilated prison, where 42 percent of inmates are considered medically high-risk. By June 30, about 1 in 3 San Quentin prisoners had tested positive, along with 106 prison staff. Thirty incarcerated people were hospitalized, including 16 sent to ICUs, according to a recent filing in an ongoing lawsuit over healthcare in the California prison system. San Quentin now accounts for more than half the coronavirus cases in the state’s prisons.

The rapid spread of the virus inside San Quentin was predicted by a group of health experts who toured the the facility on June 13. They visited at the request of the federal receiver who had been appointed by a judge to oversee health care in California’s prisons. In an urgent memo, the experts reported that the outbreak, then affecting 16 prisoners, could develop into a “full-blown local epidemic and health care crisis in the prison and surrounding communities.”

The memo’s authors praised the medical providers at San Quentin but highlighted the lack of air flow and space throughout the aging facility, which is at 112 percent capacity and particularly vulnerable because of its age and design, according to Stefano Bertozzi, the former dean of the University of California-Berkeley public health school. In the North and West cell blocks, which hold about 1,600 people—including 300 with four or more COVID-19 risk factors, according to the public health experts—windows are welded shut. Air is recirculated among five tiers of two-person cells, passing freely through grates or bars that open onto narrow walkways. James King, an activist with the Ella Baker Center who was released from San Quentin in December, describes the North and West cell blocks as “concrete boxes” where illness routinely spread in waves. “We used to joke and call it that we were living in a petri dish,” King says.

The lower-security dormitories at San Quentin are also packed, as is a gymnasium filled with rows of bunks that the public health experts said was at a high risk for a “catastrophic super spreader event.” Prisoners in the dorms share toilets, sinks, showers, and phones. (CDCR says that access to phone calls, and showers is staggered to allow for disinfecting between each use.) “I got one person who lives about eight inches away from my face,” says Kerry Rudd, who lives in a San Quentin dorm of about 100 people. “And of course the person on the bunk below me, he lives about four feet from me.”

In their memo, the public health experts strongly recommended cutting San Quentin’s population in half as soon as possible. “It’s not possible to keep people safe in that environment without moving them out,” says Bertozzi, one of the authors of the June 13 memo. Thousands of incarcerated people, Bertozzi says, needed to be moved to hotel rooms, dorms, or unused hospitals where they could be quarantined for 14 days, tested, and then released from prison. “Any number of options would be better than having those people remain in an explosive outbreak as it’s happening,” Bertozzi says.

Yet large-scale releases from San Quentin have not happened, despite the public health experts’ recommendations and sustained pressure from anti-incarceration activists, who point to CDCR statistics showing that in 2018, 59 percent of San Quentin inmates were considered to be at the lowest possible risk of reoffending. The prison has a mixed reputation—known both for the sensational crimes of the men housed on its death row and for its wealth of rehabilitative programs, including the prisoner-produced San Quentin News and the Ear Hustle podcast. “For years, San Quentin has been the vanguard of the best prison you could get to if you were a lifer who was trying to turn your life around,” King says. “There are just a lot of people who have done a lot of time, who haven’t been in trouble in a long time, because you can’t get to San Quentin if you’re a troublemaker.”

Since the start of the pandemic, state officials have granted early releases to 3,500 people across the prison system—a tiny fraction of its roughly 113,000 total prisoners. Gov. Gavin Newsom, who called the San Quentin outbreak a “deep area of focus and concern” at a briefing last week, said that prison officials had identified an additional 3,500 people who were close to finishing their sentences and met specific criteria for release. On Monday, Newsom added that there are plans to reduce San Quentin population to 3,082 in “the next few weeks,” adding he is considering transferring some prisoners to facilities in Kern and Alameda counties. “I am going through individual by individual, people with medical needs that are acute, people we are fast tracking, expediting parole review,” he said.

As of July 1, CDCR began implementing a “community supervision program” to let more people go, according to a recent court filing. But of 110 people identified as eligible for early release at San Quentin, 70 may not be released because “they don’t have a place to stay” on the outside, Newsom said last week. Meanwhile, the San Francisco Public Defenders office plans to ask a court to release roughly 60 of its clients at San Quentin, many of whom are serving life sentences for a third strike.

“I want to know why large-scale releases are off the table,” says King. He lists some of his friends inside, such as a 79-year-old who had heart surgery last year and a 66-year-old who recently learned his cancer had returned. “I want to know why they are not allowing science and medical advice to drive the decision making.” Bertozzi, too, is frustrated by the lack of releases. “People talk about fear on the part of the governor’s office that the law-and-order folks will make hay out of this,” he says. “If California—with a veto-proof majority in the legislature and, in theory, a sympathetic governor—can’t act quickly to do something here, I really don’t understand it.”

Meanwhile, the federal judges presiding over two long-running lawsuits involving medical and mental-health care in California prisons have grown insistent that officials seriously consider releasing more prisoners. At a hearing Thursday, US District Judge Jon Tigar urged corrections officials to let people out. “I don’t have the power to order the release of medically vulnerable inmates, but the state does have that power and it is imperative that the state exercise that power immediately,” Tigar said. “If CDCR does not release and physically distance in its facilities it will face more outbreaks like at San Quentin, and there will be needless deaths.” On Friday, Chief District Judge Kimberly Mueller requested that state officials brief her on whether Newsom is planning additional releases—and on whether she should convene a three-judge panel to consider ordering releases if the governor won’t.

In lieu of releases, San Quentin officials have tried to manage the outbreak by shifting people around the prison’s limited facilities. At first, prisoners who showed symptoms or tested positive were sent to the Adjustment Center, the highest-security unit, where the cell doors are made of solid concrete. Others who needed to be quarantined were sent to Carson, a unit known as “the hole” and typically used to isolate prisoners awaiting disciplinary action. As a result, according to advocates, some prisoners have been refusing to take COVID-19 tests for fear of being put in solitary confinement. People on death row have reportedly refused tests because of concerns that nurses were not changing their gloves. Prisoners know that if they report symptoms, Rudd says, “they’re going to be whisked away to the worst possible place in the universe that they can do their time.”

As the number of sick prisoners skyrocketed, the prison set up air-conditioned tents that could house up to 60 people. More prisoners may be moved into a chapel, according to a recent court filing. On Tuesday, CDCR said it would convert San Quentin’s Prison Industry Authority furniture factory into a 220-bed “alternative care site” to treat COVID-19 patients, and begin implementing 15-minute, point-of-care testing onsite.

For the people who remain inside, those who aren’t sick with the virus are sick with fear. “There’s people just going crazy with anxiety,” Rudd says. “It’s like a horror movie when you’re watching like a monster inch its way towards you and you haven’t no way out, you have nowhere to run. Us being locked in here, it’s like we’re watching this virus get steadily closer to us and there’s nothing we can do.” A group of men who tested positive for COVID-19 and were moved to the Badger unit went on hunger strike last week to protest “dismal” conditions under the lockdown, according to NBC Bay Area.

On the outside, people with family and friends in San Quentin are sharing what little information they can glean from threads of text messages and private chat groups, struggling with a lack of communication from officials and people inside. “People are trying to be resilient and comfort each other, be there for each other in the ways that we can even though we feel like deeply powerless about it all,” says Emile DeWeaver, who was released from San Quentin less than two years ago but still has a brother and close friends inside. He’s outraged that they are trapped in a place where they are exposed to such danger. “It’s a hard thing to deal with,” DeWeaver says. “It’s like, I just—I just escaped this. The thing that’s hard about that is, I didn’t escape it because I was any more deserving than anyone that is in there. It’s just dumb luck.”

Jordan has been trying to help families with loved ones inside San Quentin while struggling with how to comfort Gabe from afar. They weren’t able to speak by phone for weeks. “It’s just heartbreaking to think of someone who’s the strongest person I’ve ever met, who’s been through unspeakable violence and came out the other side a compassionate person who wants to help others heal—for them to be giving up hope right now,” Jordan says. “I don’t have an answer that’s helpful. Like, ‘Yeah, baby, we’re gonna pray, we’re gonna do everything we can, we’re gonna fight, and we may not be able to beat this situation you’re in, where you are trapped. I can’t knock down that wall and get you out.'”