When a group of teenage environmental activists started a health survey of their Central Valley town, they were prepared for the usual problems plaguing the mostly Latino, mostly poor residents: Asthma, perhaps connected to diesel fumes from the thousands of trucks rolling down the freeway nearby. Cancer, perhaps from the pesticides sprayed on the vineyards and orchards all around. Obesity and diabetes, perhaps linked to the lack of local supermarkets. What they didn’t expect was to knock on door after door to hear of babies born dead, or with severe birth defects. Of 25 births over 14 months, researchers discovered five serious birth defects (three of those babies died). Ever since then, the town and its supporters have been demanding answers: What is killing the babies of Kettleman City? You can read the full story here.

Waste Management Inc., the nation’s largest waste-disposal company, operates a vast hazardous-waste dump three miles from town. The Kettleman Hills landfill is the biggest toxic-waste dump west of Alabama, where another Waste Management facility is located in another poor, minority community. California’s two other toxic-waste dumps are also located near Latino farmworker towns. Despite Kettleman City’s remote setting amid almond groves and tomato fields, its residents are exposed to a startling array of toxic chemicals.

Maricela Mares-Alatorre, a 38-year-old teacher, describes Kettleman City as having, “A Mayberry feeling with a Latino twist—that’s why I stay. Even if I left, that doesn’t mean the problems get solved. There are still vulnerable people here who can’t speak for themselves, and we’re supposed to abandon them?”

Maricela Mares-Alatorre has been battling Kettleman City’s hazardous-waste dump for years; her son Miguel, 15, is part of a youth group called Kids Protecting our Planet. “We’re people just like you,” he told white ranchers and Waste Management employees at a Board of Supervisors meeting. “We’re tired of all this dumping and toxic waste. We want it out.”

Kettleman City mothers—including Magdalena Romero, left, and Maura Alatorre, center—show photos of their babies to EPA officials.

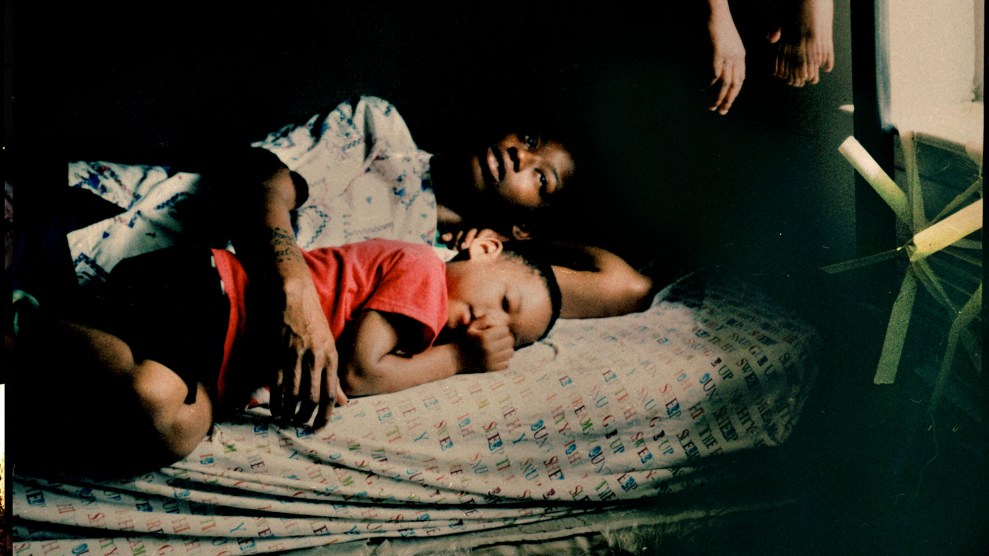

Kettleman City resident Maura Alatorre with her son, Emmanuel, who was born with a cleft lip.

A wooden cross made by a friend hangs in one of the Romero household’s two shrines to baby America, who died at five months. “You feel all the time, every hour, that something is missing,” says Magdalena Romero of her lost child.

More than half of Kettleman City’s labor force consists of farmworkers who are routinely exposed to toxic pesticides. Residents can smell the chemicals sprayed on the fields that border the town.

Residents blame the recent spate of birth defects on the vast hazardous-waste dump three miles from town. But Kettleman City has numerous environmental villains, including contaminated tap water, heavy air pollution, and daily toxic pesticide exposure.

Kettleman City children at Templo Betel, one of three churches in the town of 1,500.

Maura Alatorre’s second child, Emmanuel, was born in May 2008 with numerous problems, including a cleft lip and an enlarged head. He continues to have allergies so severe that his doctor prescribed medication usually reserved for older children.

There are projects in the works to build a massive natural gas power plant nearby, as well as to deposit 500,000 tons per year of Los Angeles sewage sludge on nearby farmland.

Photographer Justin Maxon: “Never before have I witnessed such an empowered local movement against oppression. Grandfathers, daughters, and grandchildren—all have found their voices to bring justice to their small community. Witnessing this is quite a marvelously uplifting thing.”

Kettleman City resident Ivan Rodriguez, 29, with his son, Ivan, who was born with a cleft palate.

Ivan Rodriguez dressed in his Sunday best. Ivan, like other Kettleman City children, was born with a cleft palate.

More than half of Kettleman City’s labor force consists of farmworkers who are routinely exposed to toxic pesticides, and residents can smell the chemicals sprayed on the fields that border the town on three sides. Here, farm laborers head to work in the blueberry fields.

Magdalena Romero’s daughter Alondra, 6 (second from left), with friends in Kettleman City. Alondra’s sister, America, was born with multiple birth defects and died as an infant.

An aerial view of oil storage tanks next to the California Aqueduct. The state Department of Toxic Substances Control is testing the aqueduct for toxic chemicals; some Kettleman residents eat fish from the waterway.

Tanks outside town hold the oil extracted in the Kettleman Hills. Street names like General Petroleum Avenue and Standard Oil Avenue are as close to oil wealth as Kettleman City gets; nearly half its 1,500 residents live below the poverty line.

Fast food chains abound at the I-5 Kettleman City exit, about halfway between LA and San Francisco. The town itself has no pharmacy, high school, movie theater, supermarket, or clean drinking-water supply.

Because Kettleman City tap water contains arsenic and benzene, most families rely on bottled water. Some travel 32 miles to Hanford, the county seat, to buy drinking water. Despite Kettleman City’s remote setting amid almond groves and tomato fields, its residents are exposed to a startling array of toxic chemicals. Nearly 100 trucks spewing diesel fumes roll through town daily on Highway 41, and many more come by on Interstate 5.