Mary Calvert/ZUMA Press

This story first appeared on the Guardian website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In September 2007, a rising star of Alaskan politics dared to take on one of the toughest, most challenging issues for any leader: climate change. That summer, seasonal ice cover had fallen to its lowest extent since satellite records began in 1979, leaving much of the Arctic as open water. A few months earlier, Al Gore had won an Oscar for An Inconvenient Truth.

It seemed as if the timing was right to deal with climate change, and so the politician approached a group of high-level officials to develop a climate change strategy for Alaska.

Their leader was Sarah Palin, the then governor of Alaska before her entry into national Republican party politics. “Climate change is not just an environmental issue. It is also a social, cultural, and economic issue important to all Alaskans,” said Palin, announcing two new working groups on climate change.

“As a result of this warming, coastal erosion, thawing permafrost, retreating sea ice, record forest fires, and other changes are affecting, and will continue to affect, the lifestyles and livelihoods of Alaskans,” she went on.

The focus on climate was temporary. Once Palin joined the Republican ticket as the running mate to John McCain in the 2008 presidential elections, Palin dismissed climate science as “snake oil”. The causes of climate change—and its remedies—remain disputed territory in Alaska.

There is no disputing the real-time effects of climate change. Alaska is warming faster than anywhere else in America, setting off a circumpolar scramble for oil and other resources given up by the melting ice and threatening the livelihood of those who still live off the land and the sea.

“Up here in Alaska, I would say most people do not have an argument that climate change is happening because we see it,” said Douglas Causey, a wildlife biologist at the University of Alaska at Anchorage. “The debate is not whether climate change is happening. The debate is over what’s causing it.”

But those debates, and the fierce politics surrounding climate change, compromise efforts to deal with the causes and protect the people who will bear a huge part of the consequences.

Palin in late 2007 was still in her first year as governor of Alaska, and climate change was not yet the defining issue it was to become for America’s conservative politicians.

She followed up her announcement of high-level climate change action groups by committing an even bigger conservative heresy, signing Alaska up as an observer to the regional cap-and-trade partnership, the Western Climate Initiative.

During Palin’s time as governor high-level groups of officials brought in consultants to look at ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from Alaska’s oil industry and other sectors of the economy. Another set of officials worked on trying to protect Alaska’s infrastructure from flooding and erosion, and the extreme storms along the coast.

The legislature sanctioned more than $12 million to help native Alaskan villages—like Newtok on the shores of the Bering Sea and 400 miles south of the Bering Strait that separates the US from Russia—trying to shore up their communities from erosion and other climate risks, or relocate.

But Palin’s efforts did not survive her brief tenure as governor. Her successor, Sean Parnell, quietly retired the cabinet and the “immediate action” working group. Neither group has met in at least two years.

The authorities in Alaska are still acutely aware of the changes under way in the polar region. State officials are working hard to position Alaska for an age in which shipping traffic across the pole doubles every year and international concerns compete to mine the vast oil, coal, zinc and copper deposits beneath Arctic waters.

Alaska’s leaders are also realizing the costs of a warming Arctic. The state spends $10 million a year to repair roads that buckle with melting permafrost, said Larry Hartig, who heads Alaska’s Department of Environment.

But recognition of the opportunities—and costs—does not quite translate into explicit recognition of climate change and its impacts in real-time, or even on a human time scale.

Alaska’s lieutenant governor, Mead Treadwell, likes to talk about climate change over a period of 10,000 years .

Larry Hartig, who oversaw the work of the climate change sub-cabinet established by Palin, now dismisses the original reasons for the body’s existence.

“I don’t look at climate change as a subject in and of itself,” he said. “Coastal erosion and flooding, well, we would have them even if we didn’t worry about climate change.”

He went on to explain that he would prefer to deal directly with the impacts, rather than be drawn into that “other debate”.

But from Tom John’s perspective, it is hard to separate the two. John, now in his 50s, was for years counted among the best hunters in Newtok. The status is confirmed by the dappled hide of a muskox stretched out to dry outside his home. Inside, his wife, Bernice, has taken out a whole halibut to defrost for dinner from a freezer chest that is full of frozen fish and meat from previous expeditions. “Our entire world is a grocery store,” said Bernice.

When John was a younger man, there was a rhythm to the days and seasons. April brought pike fish and white fish, seal and walrus. High summer on the Bering Sea brought herring, flounder and sometimes king salmon, and berries back on land. Winter brought mink, muskox, and otter, which John used to sell to a fur trader.

A hunter could strike out in almost any direction from Newtok and be assured of coming back with food. John’s favourite route was out towards the ocean, five or 10 miles south, to catch bearded seal. Those patterns have now been thrown off by the changing seasons, he said.

“It seems like during the fall-time the freeze-up is getting late. I used to travel through the month of October, and I could travel through the snow without any problem, without jamming through ice,” he said. “But today winter is getting late. It comes late, probably November, and I also noticed the snow pack seems harder. When I try to shovel, it’s like cement. It’s really hard to dig.”

There are other changes on John’s calendar: shorter, warmer winters, earlier springs, and the floods and rising waters that, within the next decade, could make Newtok disappear entirely beneath the Ninglick river.

The river has been clawing away at the land, reducing Newtok into a small, and shrinking, island. The villagers are desperately trying to move to a new site, nine miles to the south, before the entire village is engulfed.

The Army Corps of Engineers estimates that the highest point in the village—the school—could be under water by 2017.

The village where John has lived since he was a boy could disappear. His way of life, a subsistence economy which survived the arrival of snowmobiles, food stamps, and online shopping at Walmart, was also threatened.

The migration habits of the animals and fish on which the John family and others depend have changed over time. Some of the animals are scarce now on the Bering coast.

Seals of all variety are still plentiful off the Bering Sea. Outside one house in Newtok, the bodies of seven seal are stacked up behind a snowmobile like frozen firewood.

But walrus have grown hard to find. “Twenty years ago, I could see walrus, and hardly see the end of them. There were lots of them, thousands, but today I don’t see that any more,” said John.

Alaska is warming at twice the rate of the rest of the country, with a nearly 4F increase in average statewide temperatures since 1949, according to the US National Climate Assessment draft released last January. Temperatures could rise by up to 22F by the end of the century unless there is bold action on climate change, the report said.

On land, the glaciers are melting, and at a faster rate than ever recorded. Land that had been shored up by frozen layers of permafrost has softened and sunk. The first snow now arrives on average two days later than it did a decade ago, and melts four to six days earlier in the spring. Rivers swollen by heavier rain and snow flood more often.

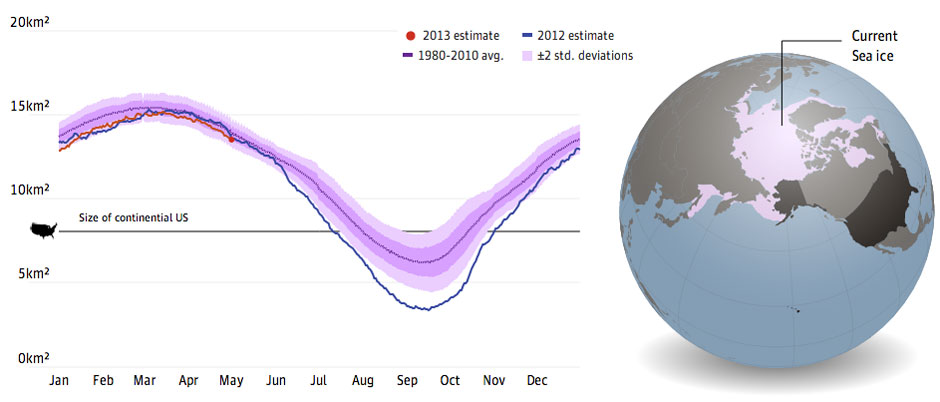

At sea, the summer sea ice has melted and thinned, leaving open waters. Last year saw the biggest loss of summer sea ice in the Arctic since satellite tracking began in the 1970s. At the height of summer, less than a quarter of the Arctic was under ice.

As the ice gives way, scientists have steadily been revising their estimates of when the Arctic would be entirely ice-free. Only a few years ago, most scientists put that date off until mid-century or beyond. Not any more—scientists are now converging around a date of 2030 for an entirely ice-free Arctic in the summer. A few outliers have even suggested an almost ice-free Arctic in the summer as early as 2020.

The Arctic will still freeze over every winter, long after the summer sea ice is gone. “I don’t think we can expect a year-round ice-free Arctic anytime soon,” said Prof Wieslaw Maslowski, an oceanographer at the US naval postgraduate school in Monterey, California.

But the remaining ice will be thinner, 2m or less, compared with the older ice layers that extend up to 4m deep. After several years of record melts, barely 5% of the ice in the Arctic has lasted for four or more summers, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Centre in Colorado. The remaining ice, which is thinner, is more susceptible to melting.

The retreat of that ice has left large areas of coastline far more exposed to storms. Those shorelines no longer have ice barriers to blunt the impact of storm surges. And the larger areas of open water produce bigger waves.

Those changes have invaded native Alaskan villages as well. Flood waters engulf village boardwalks during spring break-up. Extreme storms make it unsafe to go out hunting or trapping. Nobody feels safe or secure.

And then there is the erosion that has made life so precarious in so many native Alaskan villages. Coastal erosion rates in the Arctic are among the highest in the world, because of increased wave action from the Bering Sea.

In some areas, erosion rates have doubled since the early 2000s, according to a report prepared by the Department of Interior last month.

“The truth is that almost all of our communities will at some point or at some period of time experience some problems associated with climate change,” said Patricia Cochran, director of the Alaska Native Science Commission. “We are the first populations that are really seeing the immense changes that are occurring.”

“It certainly takes a toll … It’s in your face every day and it’s not something you can run away from,” she said.

Since the time Alaska’s governor decided the state no longer needed to plan for climate change, Bernice and Tom John have lived through two spring floods and two ferocious autumn storm season.

Their house, which sits relatively far from the Ninglick River, has had water lapping at the door.

In that time, Newtok has lost sewage lagoons and its water supply, which was contaminated by salt water and sewage. Boardwalks have sunk into the mud, because of melting permafrost.

A few families have scrapped their traditional ice cellars, buried in the permafrost after melting made them unreliable as food stores. And the Johns watched the Ninglick river rip the land out from under them.

The couple hope the authorities, and their own village leadership, mobilise in time to complete Newtok’s move to the new village site at Mertarvik before it is too late.

Bernice has heard people talking; if the village does not move to the new site in time, the villagers will be moved to Fairbanks, hundreds of miles away.

The idea scares her. “That’s unknown territory,” she said. But whatever lies in store for Newtok, it won’t be long now, Bernice figures. “We’ve got about two years, that’s what I think,” she said. “Two years.”