Rashid Ali hugs his seven-year-old son, Rahil, who has been diagnosed with torch infection and lissencephaly. Children with similar conditions have an average life expectancy of less than 10 years.Alex Masi

Before dawn on December 3, 1984, a pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, exploded and leaked 45 tons of methyl isocyanate. Half a million people came in contact with the toxic gas and other chemicals, and thousands died within days. As many as 25,000 people are thought to have eventually perished after exposure to the gas, which causes nerve and respiratory damage.

Union Carbide, the American company that owned the plant, initially tried to avoid any liability for the disaster, claiming sabotage by an employee. In 1989, it finally agreed to pay out $470 million—which worked out to about $550 per victim. The corporation’s CEO, Warren Anderson, spent years ignoring Indian criminal charges in his abode in the Hamptons. (A 2006 Mother Jones story explores the tangled the legal fallout from the tragedy. Anderson passed away at age 92 on September 29, 2014.) Dow Chemical, which acquired Union Carbide 17 years after the accident, has also avoided responsibility for its subsidiary’s troubled past, maintaining that the legal case was resolved with the 1989 settlement and that cleanup now falls to the Indian government.

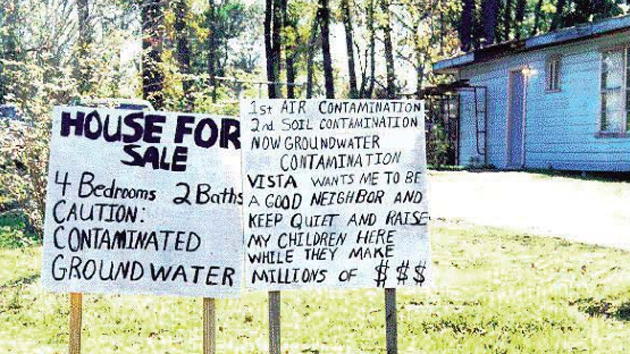

Unlike these corporations, Bhopal’s residents don’t have the luxury of moving on. In 2010, the disaster site still contained 425 tons of uncleared waste. An estimated 120,000 to 150,000 survivors still struggle with serious medical conditions including nerve damage, growth problems, gynecological disorders, respiratory issues, birth defects, and elevated rates of cancer and tuberculosis, explains Colin Toogood, spokesperson for the Bhopal Medical Appeal, which runs free health clinics for survivors. And tens of thousands of families continue to rely on heavily contaminated water from around the abandoned factory.

Sanjay Verma was orphaned by the gas leak, though he didn’t know it until he was five. He doesn’t remember the night of the explosion, but he lives with the nightmare of Bhopal’s second disaster: The failure to fully clean up the leak and the ongoing neglect of its victims. Verma’s story, excerpted below, is included in Invisible Hands: Voices from the Global Economy, a new anthology of testimonies from laborers from around the world from the Voice of Witness book series.

London-based photographer Alex Masi spent years documenting those living in the shadow of Bhopal. “I strived to portray my subjects with intimacy, meaning, and depth,” writes Masi, “in the hopes of becoming a catalyst for the promotion of awareness, action, and change for the people of Bhopal.” Though Masi’s photoessay does not picture Sanjay Varma, the images help answer Verma’s plea: “I hope that people will find out more about Bhopal. It is not just history. We are still here, and we still need help.”

For Sanjay Verma’s full story, see Invisible Hands: Voices from the Global Economy (Voice of Witness). Some of Alex Masi’s photos were featured in his 2012 book, Bhopal Second Disaster (FotoEvidence).

Sanjay’s Verma’s Story

“I grew up in an orphanage in Bhopal. I was there with my sister Mamta, who is about nine years older than me, for around ten years. We went to primary school nearby. One day when I was about five years old, we had a parents’ meeting at school, and many of my classmates came in with their parents. But I didn’t have anyone there that night. So then I realized, I don’t have parents with me. I said to my sister, “my classmates came with their parents to the meeting, but there was no one with me. Our foster mother—she’s my mother, right? So who is my father? And how come they didn’t go with me?”

And so my sister told me about what had happened. She said, “Sanjay, there was a tragedy, a disaster, in 1984. We were four brothers and four sisters and two parents. But both our parents, three sisters, and two brothers died that same night.” And that’s all she said. When she told me that, to be honest, I don’t even remember how I felt. I knew that she had answered some pretty big questions, but I still had many more.

At this time, our surviving older brother Sunil was still living by himself in the old house where we had lived before the disaster. He was just a young teenager when the disaster occurred, about thirteen, but he was allowed to live by himself rather than come to the orphanage, because he could take care of himself. I think the government was paying him and other victims living on their own about 200 rupees ($3) a month at the time. My sister and I weren’t awarded any compensation other than money paid to SOS Children’s Villages for our support.

And then when I was ten, we moved out from the orphanage and back into the house with Sunil. Soon after that, in the mid-nineties, we were given a new apartment by the government. Over 2,500 new homes were constructed by the Indian government for families who had lost loved ones who had supported them. The houses were built all in one big neighborhood that people called the Gas Widows Colony.

When we started living with our brother I began finding out more about the tragedy. We found pictures of my other siblings who had died that night, and then once in a while my brother would talk a bit about it. He would say, “one day, we were four brothers and four sisters,” and he would list their names. And then he would tell us about who our siblings had married or were going to marry, what sort of work they were going to do, everything about their lives that he could remember. He told us that our father was a carpenter in Bhopal and our mother was a simple Indian lady; she was a housewife. He wanted us to feel like we knew something about the family we’d lost.

I came to find out more about the night of the accident as well. It was my sister who took me when I was a baby and ran with me when gas started to fill the air. My brother and sister said the gas made it hard to breathe and burned people’s skin. Everyone was running. My brother Sunil had started to run, too, but he had to go pee, so he stopped in the street on the way. There were so many people running in the streets, and he got separated from us. Then, later, he fainted.

The next day when people started collecting bodies, they found my brother, and he was still unconscious. They thought he was dead. Because there was not enough firewood to cremate the bodies and not enough space in the cemeteries, they were dumping the bodies into the rivers. So they put him in the back of a truck and they were going to throw him in the river. All of a sudden my brother woke up, right before they were about to throw him in. That he woke up at that very moment was the reason that he survived—otherwise he’d have been thrown in the river and drowned.

I hadn’t known much about the tragedy or my family before leaving the orphanage, so living with my brother again really opened my eyes. My brother was very active in fighting for victims’ rights, so I began learning more and more, not just about what happened that night but also the struggle to bring the town back afterward.

After I moved in with him, I learned that in 1989, there was a settlement between the Indian government and Union Carbide for $470 million USD. As part of the settlement, Union Carbide was to provide money to build a hospital for the Bhopal gas victims, and the government would provide the land. The hospital is still there. It’s the biggest hospital in Bhopal. The government also distributed some of the $470 million settlement directly to victims of the disaster. Survivors were given $500 each for long-term injuries and about $2,000 for each family member who had died. Me, my brother, my sister, and the husband of my sister who died that night, we all received compensation money for our lost family members.

Our sister Mamta got married in 1997, a few years after we all moved in together, so after that it was just my brother and I living together. We were very close, but things could be difficult sometimes. Every time my brother talked about our family, he would get depressed, and you could see the depression in him for days. Sometimes he tried to hurt himself. Once, he tried to set himself on fire. I was not in Bhopal when he did it. I was visiting my sister in Lucknow, where she had moved after her marriage. One of my neighbors came to the door of our house just in time to save my brother. We found out my brother was suffering from paranoid schizophrenia. Later, he tried to kill himself with rat poison, too, but he survived. All this started around 1997, when I was thirteen. From that point on my brother and I were sort of taking care of each other.

In the 2000s, many of the people I met in Bhopal had health problems, especially the people who were in their thirties and forties and fifties. Most of them were suffering from breathlessness, and they got tired after walking for even five minutes. Before the disaster most of the people in town worked as laborers. They would carry wheat, or they would sell vegetables on a handcart in the streets, or they would work as masons. They lost their working ability because they inhaled poisonous gases the night of the gas leak, and many are still easily fatigued and so cannot do hard work.

I didn’t have any effects from the disaster until 2005. That year, when I was twenty years old, I had a stroke. Half my body was paralyzed for about twenty minutes, and I was in an intensive care unit in the hospital for about three days. Then I had to go through some tests in a bigger hospital, and the doctors found out that my carotid artery had narrowed, and that’s what caused the stroke. I’m not sure why it happened, whether the stroke was because of the disaster or not, but there were a lot of hard- to-explain illnesses in town.

Not only were people still sick, they were still getting sick from drinking water that was contaminated from the disaster. Those of us who were active in the movement for victims’ rights worked hard to fix the problem. I visited Delhi in March 2006 as part of a victims’ rights campaign organized by the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal. Our city was still contaminated twenty years after the disaster, our drinking water was unsafe, and nobody had ever really been held accountable for the accident. We wanted to make Dow liable for contamination cleanup, since they had bought out Union Carbide in 2001. We thought they should compensate all the people who had drunk contaminated water for twenty years and also help clean up the site. We also wanted Warren Anderson to face trial.

Around seventy people from Bhopal went to Delhi to rally and demand to see the prime minister—we walked, even though it was over five hundred miles. It took us thirty-six days. The prime minister wasn’t willing to meet us, so a few of us went on a hunger strike. I was one of the fasters, along with seven or eight others. I fasted for six days. The prime minister didn’t come, but he called us, and then three or four of our representatives went to meet him to list our demands: to set up a commission to monitor and treat the long-term health effects of contaminated air and water from the disaster; to force Dow Chemical, which had bought Union Carbide, to dismantle and clean up the old factory site; and to ensure a supply of clean drinking water to affected communities. The prime minister listened to our demands, but we didn’t get anything out of the meeting except for vague promises.

While I was in Delhi, I got a call from an activist from Bhopal who worked with my brother. She told me that Sunil had tried to kill himself again, that he had eaten rat poison and was in the hospital. I thought, He’ll be fine. I thought this because the first time he’d eaten rat poison he’d survived. Still, I took the first train home from Delhi, and my sister and her family were also on their way from Lucknow.

I arrived in Bhopal first, and it was only then that I found out my brother was dead. He hadn’t eaten poison; he’d hanged himself in our apartment. I went to see his body during the post mortem. I was so shocked. I couldn’t stop crying. And then, after a while, I was not even crying. I was just looking at him, in disbelief that I wouldn’t see him alive again. When my sister and her family arrived, my sister actually kind of fainted. And then she was crying terribly. Then her children—she had a son and a daughter by then—when they saw her, even they started crying.

I’m damn sure that my brother’s depression was because of the tragedy and the gas that he inhaled that night. He used to say things like, “Someday soon I’ll be dead.” And, “Sanjay, move to Lucknow so that you can live. Our sister, she will look after you. Or better, you should move to a big city like Delhi or Mumbai because I don’t think Bhopal is a safe place to live.” He used to talk like that. Perhaps he did not want me to live around the tragedy. Maybe he knew that his life was ruined because of the past, and that the tragedy was something he could never escape.

I didn’t want to abandon Bhopal. I moved home and dedicated my time to the campaign for victims’ rights. I wanted to be as strong as my brother had been. We have all been affected by the disaster and continue to be affected. If we don’t pressure the government, we will be forgotten. We’re making progress, though. In June 2010, eight former senior employees of Union Carbide India were finally convicted. They were sentenced to two years in jail and a fine of $2,000. They got bailed out the next day and now have an appeal in higher courts. But because of this lenient verdict there was a big media outrage. The prime minister felt pressure, and ultimately we received more compensation money for the people who had lost their family members and a commitment to clean up the Union Carbide site. Still, not much has actually improved since then—though people in areas with contaminated water have clean water pumped in now, it’s available only for a short time every day, or every other day. Much more still needs to be done.

I hope that people will find out more about Bhopal. It is not just history. We are still here, and we still need help. Today, cleanup is yet to be done, the factory still stands abandoned. What I hope for Bhopal is justice—clean and abundant water, adequate health care, land free of contamination, adequate compensation for all victims, and I want Dow, who bought Union Carbide, to take responsibility and pay for the cleanup. The people of Bhopal have fought for almost twenty-nine years, and I strongly believe that we’ll get justice one day even if we have to fight for another twenty-nine years.