<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-81311686/stock-photo-baby-being-vaccinated-by-nurse-with-latex-free-gloves.html?src=eQJx37NUJEE19RMTx/xIZA-1-18">Marlon Lopez MMG1 Design</a>/Shutterstock

In May, the Tennessean reported on a truly shocking medical problem. Seven infants, aged between seven and 20 weeks old, had arrived at Vanderbilt University’s Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital over the past eight months with a condition called “vitamin K deficiency bleeding,” or VKDB. This rare disorder occurs because human infants do not have enough vitamin K, a blood coagulant, in their systems. Infants who develop VKDB can bleed in various parts of their bodies, including bleeding into the brain. This can cause brain damage or even death.

There is a simple protection against VKDB that has been in regular medical use since 1961, when it was recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics: Infants receive an injection of vitamin K into the leg muscle right after birth. Infants do not get enough of this vitamin from their mother’s body or her milk, so this injection (which is not a vaccine, but simply a vitamin being delivered via a shot) is essential, explains pediatrician Clay Jones on the latest installment of the Inquiring Minds podcast (stream below). It’s also quite safe.

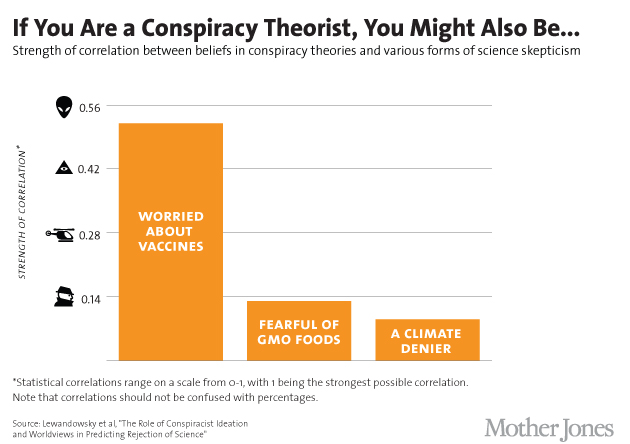

So then why are some parents refusing to get it, leaving their infants vulnerable to a potentially devastating condition? It’s difficult to understand the phenomenon outside the context of a growing fear, in general, about vaccines in the US. “There’s a lot of overlap with that anti-vaccine mentality,” says Jones. Indeed, reporting on the Vanderbilt VKDB cases, the Tennessean explained that “Vanderbilt doctors believe incidences are on the rise because of the anti-vaccine movement.”

VKDB comes in two versions, an “early” form (occurring in the first week of life) and the much more dangerous “late” form, which tends to strike infants between two and 12 weeks old who have not received Vitamin K, and who are “exclusively breastfed” by their mothers. The problem, writes Jones, is that “levels of vitamin K in breast milk are low, much lower than in infant formula.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, infants who do not receive a vitamin K injection have an 81 times greater chance of coming down with late stage VKDB. Even then the risk remains small: Between 4.4 and 7.2 infants out of every 100,000. But a Vitamin K injection is “virtually 100 percent protective,” Jones explains.

Such are the facts, yet nonetheless, parents interviewed by the CDC after bringing in their infants with VKDB showed concerns about the injection. “Reasons included concern about an increased risk for leukemia when vitamin K is administered, an impression that the injection was unnecessary, and a desire to minimize the newborn’s exposure to ‘toxins,'” observes a CDC report. These concerns are scientifically questionable at best. “Earlier concern regarding a possible causal association between parenteral [injected] vitamin K and childhood cancer has not been substantiated,” states the American Academy of Pediatrics.

A quick Google search returns a number of dire warnings about vitamin K shots circulating on the Internet. One of the top results is an article at TheHealthyHomeEconomist.com, which urges readers to “Skip that Newborn Vitamin K Shot,” before going on to list an array of “dangerous ingredients in the injection cocktail.” (The site also calls vaccines “scientific fraud.”)

And then there’s physician Joseph Mercola (whose popular website calls vaccinations “very neurotoxic” and suggests they are associated with a list of conditions, including autism). In another article on his site, Mercola suggests there is a “Potential Dark Side” to the vitamin K shot. “A needle stick can be a terrible assault to a baby’s suddenly overloaded sensory system, which is trying to adjust to the outside world,” it reads. (Although Mercola himself rejects and debunks the alleged leukemia link.) Mercola instead suggests administering vitamin K orally, claiming it’s “safe and equally effective.”

In a written statement provided for this article, Mercola elaborated on his views. He said that as a doctor, he has personally seen “direct evidence of trauma from injections,” and he cited risks from aluminum preservatives contained in vitamin K shots. “It is incomprehensible to me how any rational individual could even consider arguing the use of vitamin K injections over a simple and inexpensive, painless oral dose that has never been shown to fail,” Mercola wrote.

Jones disagrees. “We have decades of data from a number of countries, some of which have oscillated between doing the [intramuscular injection], doing the oral, and doing nothing,” he says. “And so we have good data that shows that while oral is certainly better than nothing, it is not as effective as intramuscular dosing.” In particular, with oral vitamin K, there are problems involving making sure that people take the right dose and stick to the regimen—and then of course added problems if a baby vomits up the dose. “There’s a lot of factors that could potentially interfere with the ability of the oral dosing to work,” adds Jones. “Intramuscular is the best way to do it.” (For Jones’ more thorough rebuttal to Mercola, read here.) A 2003 statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics makes a similar point, citing evidence that “oral prophylaxis” may fail more often than an injection in preventing late VKDB. (Here’s a paper discussing the cases of several infants in the Netherlands who received oral Vitamin K, but still came down with late VKDB.)

Science aside, evidence presented by the CDC suggests that refusal of vitamin K shots may be a major phenomenon to contend with. In Tennessee, the CDC found that at the hospital with the highest rate of missed vitamin K injections, 3.4 percent of infants were discharged without receiving one. At birthing centers in the state (a hospital alternative, often run by nurse-midwives), the number was much higher: 28 percent. (The agency also hinted that medical staff may not be adequately informing parents about the need for the shot.)

To prevent any more horrific brain bleeds in infants, that has to stop. The case for the vitamin K shot is irrefutable, says Jones, “especially when you take into account just how ridiculously safe these intramuscular injections are.”