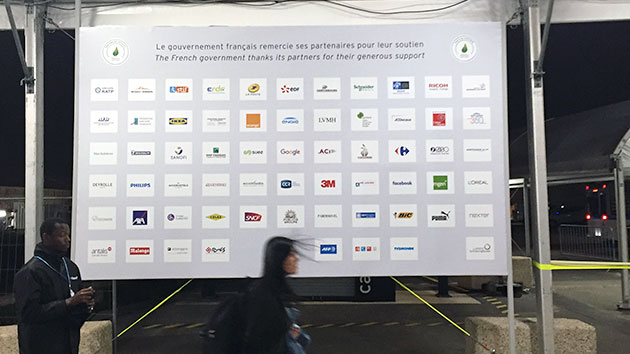

Corporate sponsorship logos at the entrance to the Paris climate summit.Courtesy Jesse Bragg

You might not expect fossil fuel companies to pay for a conference designed to shrink their industry. But in Paris, that’s precisely what’s happening.

This week and next, roughly 40,000 diplomats, activists, policy experts, and journalists are gathering in the French capital for a round of high-stakes negotiations aimed at slowing climate change. They’re packed into a regional airport that, as described by our Climate Desk partners at the New Republic, has been converted to resemble a cross between the United Nations headquarters building, Disney World’s Epcot Center, and a natural history museum.

For two weeks, all these people need to be fed, housed, transported, entertained, and equipped with space to work. Unsurprisingly, it’s an expensive undertaking—budgeted by the French government at nearly $200 million, according to EurActiv France. About one-fifth of that tab is being picked up by private corporations.

Big international conferences frequently have corporate sponsors, but given the basic aim of the Paris talks—to dramatically reduce man-made greenhouse gas emissions—some of the event’s sponsors are drawing criticism for their close ties to the fossil fuel industry. In other words, some of the companies paying to keep the lights on and the coffee flowing at the vital climate summit may have a vested interest in limiting the scope of the international agreement.

The event (known as COP21, short for 21st Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) has more than 50 corporate sponsors. They include the likes of Google, 3M, Puma, and IKEA. In exchange for providing the conference organizers an undisclosed sum of money, corporate sponsors get their logo splashed across high-profile surfaces—from billboards to banners to handouts—and priority access to spaces to hold branded events. Corporate participants can also get direct access to top-tier diplomats. At last year’s COP in Peru, for example, a lobbying group representing a handful of fossil fuel companies—including Shell and Chevron—hosted more than a dozen events, including one featuring UN climate chief Christiana Figueres.

According to a new report from the advocacy group Corporate Accountability International, several of the Paris COP’s corporate sponsors have direct ties to the fossil fuel industry, and, the group argues, a conflict of interest when it comes to the purported goals of the summit.

“It’s greenwashing,” CAI spokesperson Jesse Bragg said. “Those corporations are able to say they’re part of the solution just because they write a check.”

In particular, CAI’s report calls out three COP21 sponsors: Engie, a European electric utility company that is the continent’s largest importer of natural gas; EDF, a French electric utility that operates several major coal-fired power plants; and BNP Paribas, a multinational bank with billions of dollars invested in coal mines and coal-fired power plants. All three have massive greenhouse gas footprints, according to the report. CAI also points out that the utility companies have participated in lobbying organizations that promote the use of fossil fuels. Meanwhile, another activist group has taken aim at corporate greenwashing with a slate of billboard ads across Paris mocking energy and transportation companies that purport to be progressive, while continuing to pollute:

Beyond greenwashing, Bragg said it’s unlikely that these companies will be able to have a direct impact on the policy outcome of this COP, given how many of the nuts and bolts were worked out by diplomats in advance. But he cautioned that the creeping influence of corporations over the last two decades of climate negotiations has made diplomats overly sensitive to business-friendly solutions.

“We need to make sure these policies are created with the environment as the primary concern,” he said. “With corporations involved, you move further and further from that target.”

Spokespeople for EDF and Engie dismissed Bragg’s assertions. EDF said that its electricity portfolio contains more renewable energy than any other European utility and that it plows hundreds of millions of euros each year into clean energy R&D. Axelle Lima, a spokesperson for Engie, pointed out that the company has recently committed to stop any new investments in coal and has publicly campaigned for a price on carbon emissions.

“We have to think of solutions with governments to replace coal with another kind of energy,” Lima said. “And together we want to find a climate solution.”

Lima said it was “natural” for Engie to be a partner at the COP, given its role in the energy sector that is being reformed. She declined to specify how much money Engie had donated. BNP Paribas did not return a request for comment.

Erik Conway, a science historian who co-authored a recent book on the fossil fuel industry’s climate science subterfuge with Naomi Oreskes, said that corporate infiltration of climate summits is less important than the lobbying that goes on behind the scenes back home.

“Of course [corporate sponsorship] is a conflict of interest, just as it is a conflict of interest to have fossil fuel producing nations participating in the COP,” he said. But “I don’t think the presence of fossil-fuel producing corporations at COP meetings has had much to do with their failure to achieve meaningful agreements. It’s their economic sway with individual governments that’s the actual problem.”

To that end, Bragg thinks the UN’s climate organization could take a cue from the World Health Organization’s efforts to block tobacco lobbyists from influencing regulation of that industry. The WHO, in its international agreement on tobacco control, adopted specific protocols that require signatory countries to insulate their public health laws from tobacco industry “interference.” The climate agreement currently being hammered out in Paris could include similar language, Bragg suggested.

“The first step is the [official] recognition, in text, of this conflict of interest,” he said. “Then we figure out how we can mitigate that.”