<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-117023662/stock-photo-raw-chicken-breast-fillets.html?src=d4nYWna48R-JxK8Pk69jlg-1-2">Viktor1</a>/Shutterstock

Update: An FSIS spokesman contacted us after publication of this article to say that the USDA’s Food Safety Inspection Service announced in February 2016 that it had begun to routinely test chicken parts as part of a push to reduce salmonella poisoning. The agency set a “maximum acceptable” rate for positive salmonella tests at 15.4 percent. The FSIS will begin posting results of the tests online in August. It’s important to note that the purpose of the tests is not to prevent salmonella-tainted chicken from going out to the public. Unlike E. coli 0157, salmonella is not categorized as an “adulterant”—meaning that finding it on chicken will not trigger a recall.

One of the US Department of Agriculture’s main tasks is to ensure that the nation’s meat supply is safe. But according to a new peer-reviewed study (new link) from the department’s own researchers, the USDA’s process for monitoring salmonella contamination on chicken—by far the most-consumed US meat—may be flawed.

The process works like this: After birds are slaughtered, plucked, and eviscerated, the carcasses are sprayed with a variety of antimicrobial chemicals designed to kill pathogens like salmonella and campylobacter, and then plunged into a cold bath (which also includes antimicrobial chemicals) to lower their temperature. At that point, a few of the birds are randomly selected, rinsed, removed from the line, and put into plastic bags filled with a liquid that collects any remaining pathogens. The liquid is then sent to a lab for testing within 24 hours. (The test birds go back into the production line.) If a large number of them test positive for salmonella, the USDA knows there’s a problem and takes steps to address it.

According to the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), which oversees safety protocols in the nation’s slaughterhouses, the salmonella system works great. The agency’s latest numbers show a steadily falling incidence of positive tests for salmonella on chicken carcasses: just 3.9 percent in 2013, down from 7.2 percent in 2009.

But a new study by scientists at the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) paints a less rosy picture. The researchers simulated the FSIS’s method for testing for pathogens on chicken carcasses, and found it can turn up negative results even when salmonella is present.

Here’s why: When those birds are plucked off the line for testing, they’ve just been bombarded with antimicrobial chemicals, and traces of those chemicals can collect in the testing bags along with remaining microbes. In order for tests to be accurate, the germ-killing chemicals have to be quickly neutralized by the testing liquid. If they’re not, they can keep killing bacteria and, as the study puts it, “lead to false-negative results due to sanitizer carryover into the carcass.” And that’s exactly what happened in the simulation the researchers conducted. The authors concluded that their study “suggests that current procedures for the isolation and identification of Salmonella on poultry carcasses may need modification.”

But the FSIS disagrees with this conclusion. “FSIS is confident that our testing results yield accurate outcomes,” an agency spokesman wrote in an email. He emphasized that the ARS study was a simulation, and “did not evaluate the same practices as our in-plant personnel utilize.”

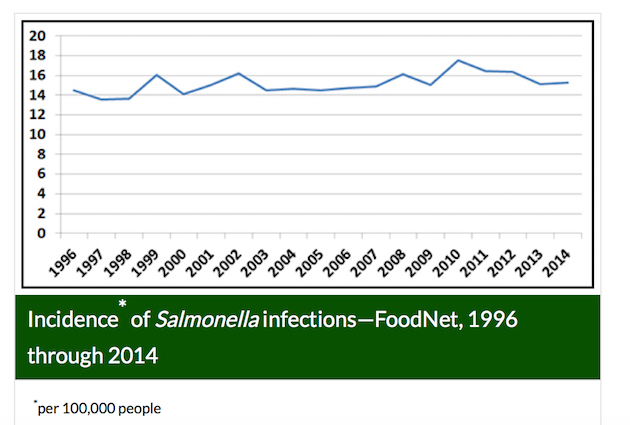

Salmonella poisoning remains a huge problem. Starting in March 2013, a salmonella outbreak traced back to chicken sickened more than 600 people in 29 states, 38 percent of whom had to be hospitalized. And—unlike the FSIS’s tests for salmonella on chicken carcasses—salmonella poisoning rates have not shown any steady decline pattern over the past 15 years. Here’s a chart from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

Not all of those infections come from contaminated chicken, of course. The CDC doesn’t break down salmonella poisoning by food source, and doing so is tricky, said Mansour Samadpour, a food safety expert and chief executive of IEH Laboratories and Consulting Group. Most chicken-related salmonella infections come from not from eating undercooked meat, but rather from cross-contamination, he said—like cutting vegetables for a salad with the same knife used to slice raw chicken. As a result, the source of a given salmonella-triggered food poisoning is hard to trace. But chicken is the “item in the supermarket most likely to be contaminated with salmonella,” he said.

And also, while the FSIS’s numbers show impressively low rates of salmonella on chicken carcasses from its carcass testing—3.9 percent in 2013, 4.3 percent in 2012—other numbers from the agency suggest the problem may be worse. In another report, based on tests conducted in 2012, the FSIS gathered chicken samples from the very end of production lines, after they’d been cut into parts, the way consumers typically buy them. They found a positive rate for salmonella of 26.2 percent—about six times the rate found the same year on the FSIS’s testing of carcasses.

For Samadpour, that huge discrepancy suggests that the carcass testing may indeed be generating lots of false negatives. That means consumers could be being exposed to salmonella-contaminated chicken at much higher rates than the FSIS’s carcass numbers suggest.

The solution is pretty clear, Samadpour told me. Instead of testing whole carcasses just after they’ve been bathed in antimicrobials, while they’re still in the middle of the processing line, the tests should happen at the end of the processing line, when the carcasses have been cut up and are ready for packaging. He said Big Chicken could learn something from the beef industry, which began testing its finished products in that manner for a virulent E. coli strain called O157:H7 in the 1990s: Rates of poisoning from that often-deadly bacteria have plunged since.

In the meantime, I’m taking extra care when prepping chicken. Here‘s how the CDC says consumers should handle it.