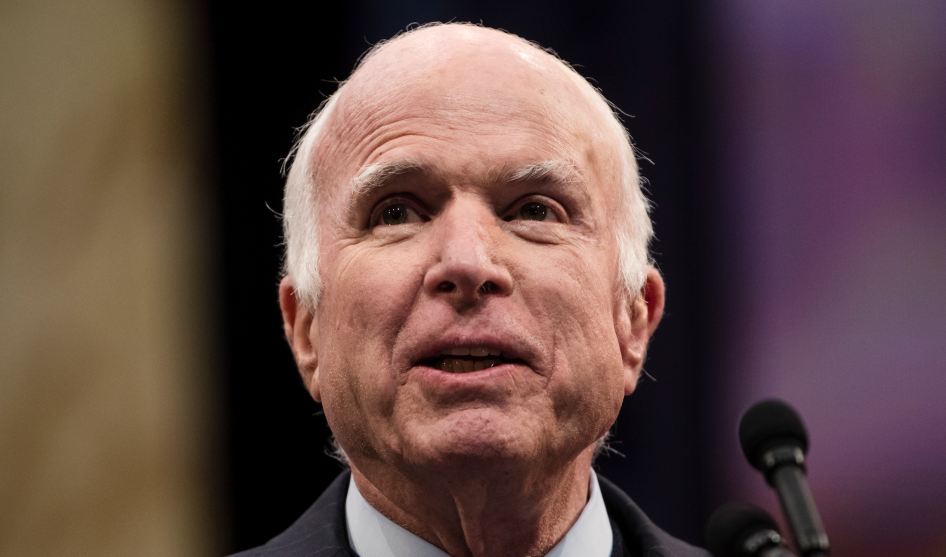

Charles Dharapak/AP

This story was originally published by Grist and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Dozens of epitaphs written over the weekend proclaim the late US Senator John McCain as an American hero. But history may miss one of his greatest achievements: His decades-long call for climate action.

The death of McCain, Arizona’s senior senator, former prisoner of war, avid outdoorsman, and two-time Republican presidential candidate, marks the end of an era of free-thinking moderate conservatives who embraced conservation as a core value.

On the campaign trail in 2000, McCain received question after question from young people on climate change. After looking into it, he realized something major had to be done. In a 2007 interview with Grist, McCain explains his reasoning succinctly: “Suppose we’re wrong, and there’s no such thing as greenhouse gas emissions, and we adopt green technologies. All we’ve done is give our kids a better planet.”

Before Barack Obama’s environmental policies, before the Paris Agreement, there was McCain-Lieberman—the 2001 cap-and-trade proposal that McCain championed during a time when the country would soon be consumed with fighting a global war on terrorism. McCain-Lieberman never passed the Senate, but it remains the most important bipartisan US climate legislation ever proposed, inspiring cap-and-trade schemes that have been implemented around the world.

On the 2008 campaign trail, this time as the GOP’s presidential nominee, he delivered what might be one of the most accurate, urgent, and passionate speeches ever given by a major American political figure on climate change. The entire address is worth reading in full, if only to lament how far his rhetoric seems from the realm of possibility today after a decade of Republican backsliding on this most-important of issues.

For example, the most stalwart of climate champions could have written this particular passage:

We have many advantages in the fight against global warming, but time is not one of them. Instead of idly debating the precise extent of global warming, or the precise timeline of global warming, we need to deal with the central facts of rising temperatures, rising waters, and all the endless troubles that global warming will bring. We stand warned by serious and credible scientists across the world that time is short and the dangers are great. The most relevant question now is whether our own government is equal to the challenge.

Of course, McCain also had his own share of backsliding on climate. His insistence on market-based climate solutions made him a frequent opponent of Obama’s regulatory approach. His nomination of Sarah Palin—the Alaska governor who popularized the “drill, baby, drill” chant—as his running mate in 2008 played a major role in unleashing a wave anti-science populism that led to our country’s present leadership. In his final days, McCain said picking Palin was one of his biggest regrets.

But McCain wasn’t afraid to bravely stand up to his own party and advocate for the environment, especially during the Trump era. McCain was one of the few Republicans strongly speaking out against the planned withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement—traveling to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef to make his plea that the US keep its commitment. And last year, McCain was still cheering on climate activists and chose to buck his party’s anti-science stances and uphold an Obama-era methane rule.

In this moment of deep division and existential challenges facing our country and our world, we’d do well to emulate McCain’s spirit of courage and ability to stand up for urgent climate action even when other problems seem all-encompassing. In his final months, when asked what he’d like to be remembered for, he wanted people to say that “he served his country.”

John McCain served his planet, too.