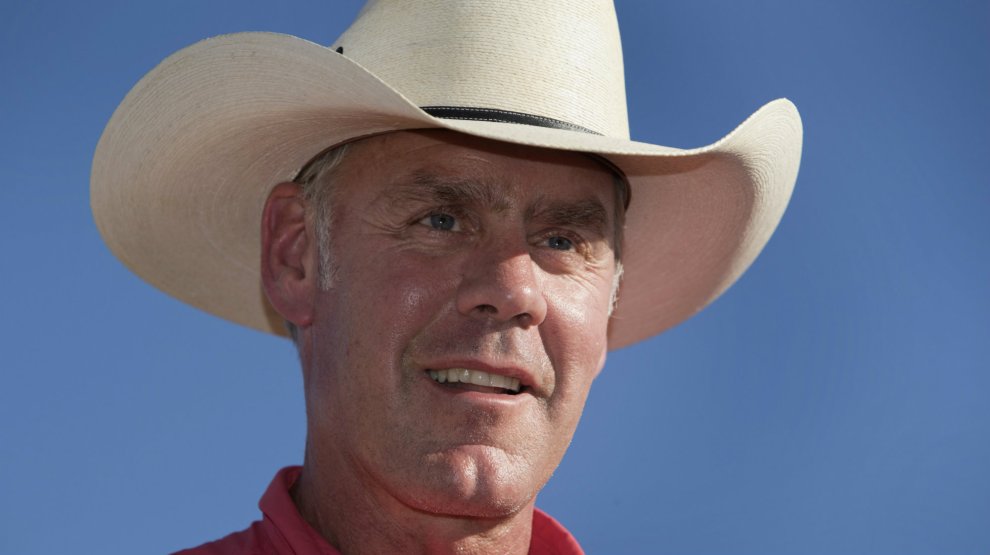

Ryan Zinke (left) and David BernhardtMother Jones illustration

With the tepid enthusiasm of an overworked elementary school principal, David Bernhardt, the second-in-command at the Department of the Interior, stood in the newly refurbished auditorium at the agency’s Washington headquarters, trying to get the staff settled down before a routine town hall with the secretary. The in-person audience at the event last winter numbered about 100, though up to 70,000 Interior employees nationwide could have watched the livestream as Bernhardt introduced his boss. Ryan Zinke, who towered over his deputy, strode to the lectern, passing Bernhardt without shaking hands.

Unlike many in the nation’s capital, acknowledgement seems less important to Bernhardt than behind-the-scenes power. And the latter he has. As Zinke ticked off the accomplishments of his first year—fulfilling the president’s vision for “energy dominance,” selling off public lands, and taking on the Endangered Species Act—he might as well have been naming feathers in Bernhardt’s cap. This stout, unobtrusive, middle-aged man in square glasses has been one of the most effective officials in the Trump administration, and after 14 months on the job, he appears to be within striking distance of taking over the department that oversees a fifth of the nation’s landmass.

Smart and generally well-liked by his colleagues, Bernhardt is regarded, with grudging respect from environmentalists, as the “brains behind the agency.”

“I found David to be very direct, precise and guarded,” says Dan Wenk, the former superintendent of Yellowstone National Park who had spent 43 years at the department and retired in September. “He understands how the Department of Interior works; he understands how to get things done.” Athan Manuel, who directs the Sierra Club’s Lands Protection Program, notes, “He’s not just a mouthpiece of the secretary. He’s the guy doing the dirty work.”

Deputy Secretary of Department of Interior David Bernhardt listens as President Donald Trump speaks during a cabinet meeting at the White House.

Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post/Getty

Bernhardt is the perfect No. 2 to a highly visible No. 1. Zinke is the folksy charmer; Bernhardt is the strictly-business lawyer. Zinke is the relative outsider, an opportunist, and a politician; Interior watchdogs say Bernhardt is the ultimate DC swamp creature. Zinke is relatively new to Interior; Bernhardt, who spent eight years at the department earlier in his career, knows the ins and outs of its labyrinthine bureaucracy. And while Zinke has been mired in scandals and faces at least six active ethics investigations—including inspector general inquiries into possible Hatch Act lobbying violations and a Halliburton land deal in his hometown of Whitefish, Montana—Bernhardt has been largely invisible. Much like Andrew Wheeler, the technocrat who succeeded Scott Pruitt after his rocky stint atop the Environmental Protection Agency, Bernhardt could seamlessly take command should Zinke succumb to ethics challenges or, as some speculate, exit to run to be Montana’s governor in 2020.

Bernhardt’s understanding of the department’s workings and the allies he’s installed in key political posts enable him to steer its complex network of decentralized offices while leaving few fingerprints. His calendars often have little detail in them; the environmental group Western Values Project has noted how few of his emails turn up in their frequent Freedom of Information Act requests to the Interior. “Kind of amazing that he can do anything without leaving a paper trail behind him,” said Aaron Weiss, media director of Center for Western Priorities, another conservation group.

“Bernhardt knows where all the skeletons are and the strings to pull,” Obama-era career Interior official Joel Clement told me. Unlike Zinke, whose well-cultivated cowboy persona is “all hat, no cattle,” Clement says, “the real work is being done by Bernhardt.”

Created in the mid-19th century, Interior was launched with a focus on managing, rather than protecting, public lands. Some of its agencies, such as the Bureau of Land Management, were established primarily to aid mining, timber, and ranching interests, with little consideration of the effect on communities or the environment. Unlike the EPA, which has a relatively focused mission of protecting the environment and public health, Interior’s bureaus are responsible for a wide range of policies and places—the land and ocean, Native American affairs, wildlife—which can present competing priorities.

The Obama administration tried to overhaul Interior’s deeply rooted culture, particularly at the Bureau of Land Management, whose fossil fuel leases are estimated to account for roughly 24 percent of the United States’ energy-related greenhouse emissions. But President Barack Obama’s efforts came late in his administration, and he struggled to put climate change at the center of the department’s agenda. Bernhardt’s bureaucratic maneuvering has proven more adept, as he’s redirected decisions once handled by field offices or agencies like BLM to headquarters. Hoping to speed up construction on public lands, he’s mandated bureaus complete federally mandated environmental reviews in less than a year and aim to keep them under 150 pages.

Late last year, Associate Deputy Secretary Jim Cason, a Bernhardt lieutenant, reassigned at least 27 executives, including several high-level staffers with portfolios in climate change and conservation, without much explanation or a paper trail. Clement, a climate policy expert, was assigned to audit oil and lease sales in the Office of Natural Resources Revenue. Dan Wenk, the veteran superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, was directed to transfer to a DC job just before he planned to retire. Both ended up leaving Interior. “It had a message to it,” Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), says.

Before resigning, Wenk took the matter of his reassignment up with Bernhardt directly, who Wenk says assured him his skills were needed elsewhere. But Wenk, who was surprised to find his negotiations about the reassignment leaked to press, told Mother Jones he saw his deployment as a signal from Interior’s new political leadership “that we’re in charge and that there’s a new sheriff in town.”

Growing up in Rifle, Colorado, a town of under 5,000 tucked among vast fields of oil and gas wells, Bernhardt manages to embody both Western sensibilities and DC swampiness. Rifle is surrounded by federal lands—some protected as wilderness, some leased for logging, mining, and drilling. Bernhardt still frequently visits his home state and recently floated the possibility of moving BLM’s headquarters to Colorado.

While in his early 20s, he served as a judicial intern for the US Supreme Court in 1990. After law school at George Washington, he landed as a legislative counsel for Rep. Scott McInnis, a Colorado Republican who then served on the House Natural Resources Committee. He left government to spend three years at Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, a lobbying and law firm, before taking a job in 2001 at President George W. Bush’s Interior Department running its congressional and legislative affairs office. By 2006, he was the department’s top lawyer, overseeing 500 employees and coordinating policy among its far-flung bureaus. His office helped provide the legal underpinning for some of the Bush administration’s headline-grabbing initiatives, including its attempts to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling and to allow snowmobiles in Yellowstone National Park. He also played a key role in implementing the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which exempted the fracking industry from certain water regulations.

After Obama’s election, he eventually rejoined Brownstein Farber, becoming its natural resources director, where he rubbed shoulders with the top of the oil and gas industry, attending conference panels and workshops with Shell executives, American Petroleum Institute staffers, the president of the Western Energy Alliance, and even Dick Cheney, the oil executive turned vice president.

Related: All The Secretary’s Men

Since riding into Washington, DC on an actual horse to take command of the Department of the Interior (DOI), Ryan Zinke has stocked the agency with a swamp-soaked stable of advisers.

In September 2016, Bernhardt took charge of Trump’s Interior transition team, sketching out the potential new administration’s priorities and compiling names for key positions. He left a few weeks after the election, before Zinke’s nomination was announced, and resumed his work with the lobbying firm until he was nominated as deputy secretary in April 2017.

While Zinke sailed through his confirmation with 68 votes, Bernhardt faced more questions. His revolving-door career led opponents of his nomination to describe Bernhardt as a “walking conflict of interest.” Many of his and his Brownstein Farber colleagues’ lobbying projects —like opposing new protections for the sage grouse, the creation of monuments like Utah’s Bears Ears, and the opening of new Indian casinos—fall under Interior’s purvey.

“The minute I walk out of that firm, I have no interest in their interest,” Bernhardt insisted during confirmation questioning. “If I get a whiff of something coming my way that involves a client or involves my firm, I’m going to make that item run straight to the ethics office.” He was confirmed in July with 53 votes.

Shortly afterward, Bernhardt submitted an ethics document pledging to recuse himself from matters directly involving more than two-dozen clients for at least one year. But Interior watchdogs have noticed a frustrating pattern: his former clients’ projects are getting approved, with little paper trail. At Interior, Bernhardt has worked with gaming interests lobbying Interior’s long-troubled Bureau of Indian Affairs and taken the lead on weakening the Endangered Species Act and protections for the sage grouse, priorities of two former clients, the Independent Petroleum Association of America and the Safari Club. Last year, Adam Federman reported for Mother Jones that Bernhardt had insisted on reviewing United States Geological Survey data on oil and gas deposits prior to publication—a break from norm with potentially huge consequences, because any leaks could move markets. A scientist resigned in protest.

For a majority of former clients, Bernhardt’s promised recusal period has already ended, making it possible for him to openly participate in decisions that could potentially enrich them and his own law firm. For example, Bernhardt could be in charge of future Interior decisions regarding a 43-mile pipeline that would connect the Colorado River to California farmland.* Brownstein Farber owns a small stake in the venture, and while working at the firm, Bernhardt performed legal services on behalf of the involved water district as well as for Cadiz, Inc., the project’s builder. While Zinke hasn’t brought up the specific project, he and the president spent the summer pushing pipelines and dams as a controversial answer to California’s wildfires.

The administration’s porcelain-smashing cabinet appointments—think Pruitt or former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson—gained wide attention during their brief tenures attempting to overhaul their agencies. But some of the most radical changes under Trump have come from the many behind-the-scenes appointees, the government insiders, who have come out of the swamp the president pledged to drain. At Interior, that’s been Bernhardt and his allies. As PEER’s Jeff Ruch warns, Bernhardt is proving very effective at the role he “was genetically engineered to do”: quietly and in some cases permanently reshaping the department in control of public land.

Image credits: Michael Brochstein/Sipa/AP; David Zalubowski/AP; songqiuju/Getty

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that according to a spokesperson for Cadiz, Bernhardt played no role in the evaluation for a BLM decision made last year and there are no current pending decisions before Interior. He also did not lobby but provided legal services for Cadiz.