Native prairie with farmland in IowaJackVandenHeuvel/iStock / Getty Images Plus

The Midwest’s farms produce corn and soybeans on an epic scale: enough to supply feed for the great bulk of the cows, chickens, and pigs that satisfy the country’s ravenous meat habit, provide a large portion of the sweeteners and fats that go into processed foods, and generate about a tenth of car fuel in the form of ethanol. Typically, there’s even enough of these crops left over each year for huge exports and surpluses.

But in the process of churning out such gargantuan bounty, these farms also leak nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer, which feed massive algae blooms. The blooms appear from Lake Erie clear to the Gulf of Mexico, where the globe’s second-biggest coastal dead zone forms every summer. Renegade farm fertilizer also fouls water supplies in cities and towns throughout the corn belt, including Des Moines, Iowa, and Columbus, Ohio, along with residential wells. Even at levels well below the US Environmental Protection Agency’s legal limit for drinking water, nitrates from fertilizer have been associated with heightened risk of bladder, ovarian, and thyroid cancer.

A new study from Michigan State University researchers points to a shockingly simple way farmers could help fix this pollution problem. And the strategy could improve their profits, which have declined sharply in recent years. All growers would have to do, the researchers posit, is retire about a quarter of the acres they now devote to corn and soybeans.

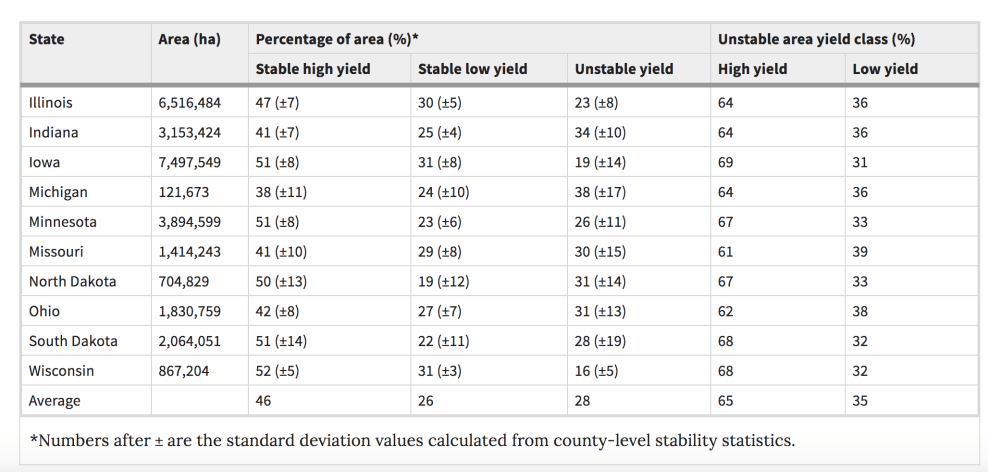

The study’s authors used satellite imagery to gauge crop yields for 70 million acres of farmland in the corn belt over eight years. As every experienced farmer who manages a substantial tract of land knows, and the MSU study confirmed, some fields tend to be winners every year, churning out steadily high yields, while others consistently lag. On about half of the land studied, crop years were consistently high year to year, the researchers found. Strong yields help cut fertilizer pollution, because most of the nitrogen applied by farmers is taken up in crops, leaving less of it in the ground and liable to leach away into streams. For another 28 percent of acres, yields were “unstable,” the paper found—good some years, bad others, depending on conditions like rainfall.

But the remaining 26 percent of acres delivered low yields every year. As this table from the paper shows, these low-performing acres are distributed widely throughout the corn belt, including in that corn-producing goliath Iowa, where nearly a third of acres regularly lag:

On average, crops in the low-performing areas took up about 45 percent less nitrogen than those in the high-yielding areas, leaving loads of the fertilizer in the ground, primed to run off and cause harm. All told, farmers are throwing away an average of $485 million a year on this excess application, the paper calculated. That waste, combined with all other costs of farming—land rent, labor, fertilizers, seeds, chemicals, and fuel for running big machines like harvesters—means growers are actually losing money planting the low-yield parts of their farms, according to the paper’s lead author, MSU earth and environmental sciences professor Bruno Basso. Depending on the growing conditions and commodity prices in a given year, they’re spending between $50 and $300 per acre more in seeds, chemicals, and other costs than they’re bringing in from selling their crops.

These economic losses are hard to notice at the farm scale because farmers look at average yields and cost-per-revenue over their entire operations, Basso says. Most growers in the Midwest use government-subsidized crop insurance that guarantees compensation when farm revenue drops, giving farmers little urgency to retire their low-productivity land.

Rather than waste fertilizer and contribute to pollution, it would make sense for growers to simply retire the 26 percent of this low-production land altogether. They could then plant it with perennial native prairie grasses that need very little maintenance after they’re established.

Because of the subsidies in place, farmers will clearly need a concrete incentive to retire their unproductive land. One model is California’s Healthy Soils Program, which earmarks state funds to pay farmers for practices known to improve soil health (more here). Converting low-yielding cropland into prairie grasses—the ecosystem that prevailed in the area before US settlers first plowed the ground for planting in the 19th century—would qualify. Restored prairie patches have been shown to trap significantly more carbon underground than crop farming. And low-yielding land tends to the very kind that’s prone to forming ephemeral gullies during spring storms, whose soil-destroying effects I wrote about here and here. Planting perennial grasses on such vulnerable land solves that problem.

The environmental benefits from such a move would go way beyond better soil management. Not farming a quarter of the corn belt would mean a big drop in those stray fertilizers polluting waterways, and also a reduction in other toxic farm chemicals—insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides—entering the landscape. Manufacturing nitrogen fertilizer is an energy-intensive process; if farmers stopped wasting it on underperforming land, they’d cut greenhouse gas emissions by about 6.8 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, the MSU paper found—equivalent to taking 1.4 million passenger cars off the road. A vast expansion of grasslands would deliver a much-needed boost in habitat for struggling birds and pollinating insects.

And because the laggard acres produce significantly less than their bumper-crop counterparts, overall soybean and corn production would likely drop at most 15 percent, Basso says—a gap that could tighten as farmers focus their skills and resources on their best land. And besides, the world isn’t exactly clamoring for the corn and soybeans being squeezed at such great environmental cost out of the Midwest’s worst-performing terrain. Overproduction of corn and soybeans was haunting the region’s farmers long before President Donald Trump’s trade wars roiled key foreign markets and pushed prices lower.

Basso’s paper points to a stunningly simple way forward for the US heartland—one that would benefit farmers and address mounting ecological crises. It would likely take a shift in federal policy, and incentives for farmers to switch to low-yielding land to prairie. It sounds like a job for the nascent Green New Deal that’s currently gestating in Congress.