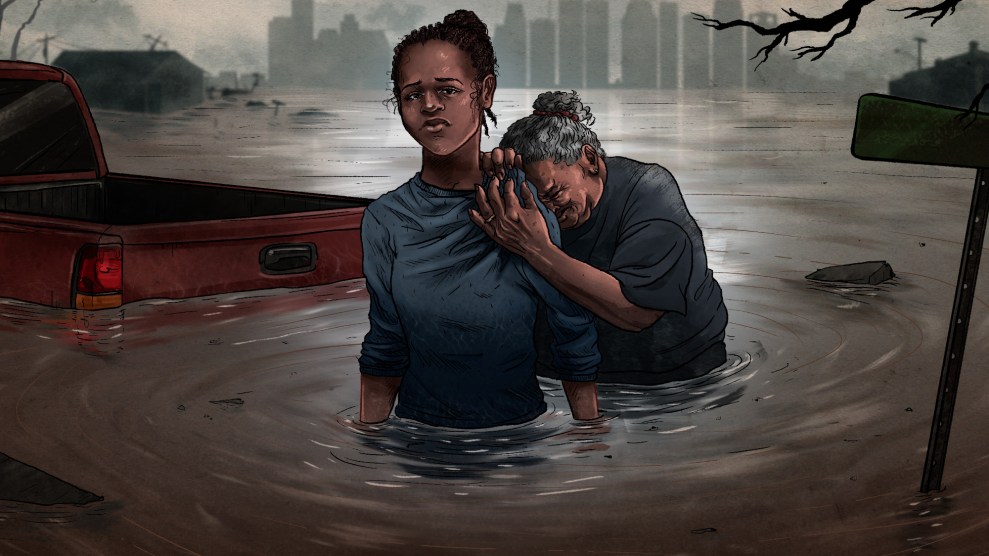

Illustration by Joanna Eberts

This story was originally published by the Center for Public Integrity and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Barbara Herndon lay in the center of her bed, muscles tensed, eyes on the television. She was waiting for the storm.

All morning on that day in late May, the news had covered the cold front slouching south from central Texas. By late afternoon, dense ropes of clouds darkened her Houston neighborhood. Rain whipped the windows. Cyclone-force gusts rent open her backyard breaker box. She cringed at the noises, chest tightening, mind on the havoc that might follow—but ultimately didn’t.

Herndon, who as a child in southern Louisiana saw her share of hurricanes and thunderstorms, had never thought much about them. Now, even a passing squall like the May storm—lasting less than an hour—will panic the 70-year-old retiree. “I get scared,” she said. “I cry a lot, easily. That didn’t use to happen.”

Herndon is among the 50 percent of Houston-area residents who have wrestled with powerful or severe emotional distress since Hurricane Harvey deluged the city in 2017, according to a Rice University survey to be published Wednesday. Studies have shown similar outcomes with symptoms of anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress following other hurricanes, floods and wildfires—natural disasters that are intensifying as climate change accelerates. Already, the U.S. has faced nearly 40 such events costing at least a billion dollars each in the past decade, more than any period previously recorded. Mental-health experts worry the psychological toll from these increasingly common cataclysms—with a pandemic now overlaid on top—could be unprecedented.

The nation isn’t ready.

The country’s primary aid for mental health after disasters is the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program, run by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Every year, the program distributes an average of $24 million, or 1 percent of FEMA’s annual total relief fund, to send mental-health workers into disaster-stricken communities and provide other support. But the Center for Public Integrity and Columbia Journalism Investigations found that this help usually lasts about a year, even though the psychological effects can linger for many more, and reaches only a fraction of survivors.

After Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico, for instance, 18 percent of the island received counseling paid for by the program even though many more were affected. In Houston, where Harvey’s flooding was widespread, less than 1 percent of residents saw counseling.

The FEMA-funded program has given out $867 million nationwide in its more than three decades of existence—just slightly more than the money one Defense Department agency lost track of in a single year.

Studies show other forms of federal assistance, like housing aid, are distributed unevenly, exacerbating inequalities and drawing out recovery for communities of color and people with less money. This, in turn, compounds the trauma and emotional burdens of a disaster.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration referred questions to FEMA, which funds the effort. FEMA said its program, often shortened to CCP, provided counseling to 1.4 million people in the past five years and gave brief help to several million more.

“The toll that disasters put on mental health is well documented and part of the reason FEMA funds the CCP,” a spokesperson wrote in an email. The program, however, “exists to supplement, not supplant, state, local, tribal, and/or territorial resources.”

But more Americans are affected by climate-driven disasters every year, with serious emotional consequences. Even with FEMA aid, state and local resources aren’t enough.

Public Integrity, CJI and newsrooms across the country asked people affected by hurricanes, floods and wildfires—and the professionals helping such survivors—to share their experiences. More than 230 responded to the online survey, most from regions repeatedly hit by disasters in the last decade. That ranged from Puerto Rico, struck by seven major storms, to some Northern California communities fighting wildfires every year.

Seventy percent of the survivors said they did not get mental-health services after their experience, for reasons ranging from cost to their belief that they didn’t need help. But the struggles they linked to the disaster—from anxiety and depression to trouble sleeping—suggest that many could have benefited from the support. Over 60 percent of survivors reported five or more types of emotional challenges in the first year after the disaster.

In Naguabo, Puerto Rico, Jonathan Alverio Rivera started having flashbacks after Maria slammed into the island in 2017. He lost power for three months, reliving the terror in the dark. Alverio Rivera, now a 29-year-old medical student, says he needed mental-health aid but couldn’t find any. “I didn’t see any ads or anything saying, ‘If you need help, call this number,’” he said.

In Magalia, California, Mickey Dukes, 65, lost her job as a medical technologist when the 2018 Camp Fire—the state’s deadliest and most destructive wildfire—burned through her town. The hospital where she worked closed and many of her friends moved away. “The feeling of loneliness is overwhelming,” said Dukes, but “we don’t really have very good mental-health services.”

And in the rural Midwest, where those services are often spare to nonexistent, punishing floods in recent years have sowed trauma. Sharon Stewart’s community of Pacific Junction, Iowa, was largely wiped out by 2019 flooding. “We’ve had a really, really, really rough year since then,” she said. “There’s so many people that went through so much.”

As scientists warn that the warming climate will keep adding fuel to extreme storms, Texas is a bellwether. In the last 10 years, the state faced 15 federally declared major disasters for storms or wildfires—six in the Houston area alone. Harvey, dumping more than 19 trillion gallons of rain on the state, was by far the worst. After that storm, FEMA awarded Texas $14 million for the counseling program, helping 200,000 survivors, officials say. But records show the number that received counseling is far lower. And many residents believe they’ve been forgotten.

(Lucio Vasquez/Center for Public Integrity

That’s particularly true where Herndon lives, northeast Houston, with its lower-income, majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods shaped by a long history of discrimination and increasing risks of floods. Three years after Harvey, some there are still rebuilding and the storm’s toll on mental health remains palpable, residents and community leaders say. The spread of COVID-19 through the city is yet another disaster piling stress onto residents with too much already. And the threat of more powerful storms is ever-present.

“It’s becoming routine, and that is not good,” said Robert D. Bullard, an environmental justice scholar at Texas Southern University in Houston. “That is not good.”

A storm’s long shadow

For Herndon, the trauma started on August 28, 2017. Harvey was, by then, into its fourth day assaulting southeastern Texas.

At around 2 a.m., when Herndon stepped out of bed to use the bathroom, her toes sank into cold water. “No,” she remembers saying to herself. “No, no, no, no.” Three inches of musty, tea-colored water had seeped into her one-story home. And it was rising.

She had seen this 16 years earlier during Tropical Storm Allison. She and her husband, Oscar, stayed in the house all day, the water rising to their calves before they finally fled. Oscar, with a chronic lung condition, died a year-and-a-half later—a death hastened by stress, Herndon believes.

Now, amid Harvey, she was on her own, with the rain picking up fast. Neighbors were making for dry land on air mattresses or trying to wave down helicopters. It took her nearly 10 hours to find a rescue boat. By then, she was chest-deep in floodwater and emotionally numb.

Days later, Herndon returned home. Furniture, floors, walls—everything was spoiled. She had married Oscar in that living room and promised him, as he lay dying, that she’d never sell; his spirit was there, she said. Harvey took that away.

She was so focused on survival—applying for the housing and property aid she desperately needed—that months passed before her feelings finally caught up to her. By winter of that year, she remembers feeling drained and lonely. She was crying more and more. She recalls praying for a change one night.

“God,” she asked, “why’s this got to be so hard?”

A small amount of help

FEMA’s Crisis Counseling Program was made for people like Herndon. But she says it never reached her.

Established in the 1980s as a short-term disaster relief grant, the program funds free emotional help for anyone affected by a major disaster. It’s been used in every state, plus Puerto Rico and other territories, for more than 400 traumatic events in all.

States with some of the most damaging climate-related catastrophes in the last decade said they rely largely—often entirely—on the program’s funding to support disaster survivors’ mental health. That typically includes state hotlines and crisis counselors who, until the pandemic hit, would go into communities and offer help in person, sometimes door-to-door. After floods and hurricanes in South Carolina, for instance, counselors showed up to town halls, local meetings, even Christmas parades.

States are required to plan for the mental-health consequences of disasters. Officials said they’re grateful when they get CCP funding and appreciate the flexibility to plan the response they think will suit their communities best. But the way the program works can also impede efforts to help.

Though disasters always impact mental health, states don’t automatically get the funding. Wildfires often aren’t deemed large enough to qualify. When events do pass the magic threshold, states must complete long applications justifying the need. Iowa’s most recent request, for instance, ran 168 pages. And states must fill out two applications if they want to access the full program because FEMA splits it into “immediate” and “regular” phases. The second application can take months to be approved.

The agency’s reasoning is that states should only receive assistance if the event would overwhelm existing mental health services. But that’s almost always the case for major disasters, said Karen Hyatt, emergency mental health specialist for the Iowa Department of Human Services.

“Even when … other FEMA programs are up and running, crisis counseling program administrators are still writing the grant,” she said.

In wildfire-prone California, where counties provide much of the mental-health response to disasters, local officials have found the federal program difficult to manage in part because they were on the hook to pay upfront. “It took a long time for them to get reimbursed,” said Michelle Doty Cabrera, executive director of the County Behavioral Health Directors Association of California.

Then there’s the problem of how long funding lasts. The program typically ends after a year, even though studies show that emotional burdens can persist far longer.

“When you’re talking about mental health, recovery takes years,” said Dr. Karen G. Martínez, director of the University of Puerto Rico’s Center for the Study and Treatment of Fear and Anxiety. “Disaster programs don’t really address that.”

Of the nearly 200 survivors that responded to the survey by Public Integrity, CJI and partner newsrooms, a third were still reporting five or more types of emotional struggles today—at least three years post-disaster, in many cases. Though people across the country participated, the survey isn’t nationally representative, and it may have drawn respondents who are more affected by disasters than average.

But this finding echoes earlier research: Epidemiological studies found emotional disturbances three years after Superstorm Sandy in 2012. One study of low-income mothers affected by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 discovered one in six with post-traumatic symptoms 12 years after the storm.

And the new reality of back-to-back disasters gives people little time to heal, said Amber Twitchell, associate director at On The Move, a social-services organization in California’s Bay Area. Since the Sonoma Complex Fires in October 2017, she said, “We have been in a constant state of disaster response.”

Public Integrity and CJI reviewed the Crisis Counseling Program response to six major disasters: Floods in Missouri and Iowa; the Camp Fire in California; and Hurricanes Harvey, Maria and Florence in Texas, Puerto Rico and South Carolina, respectively. The program’s reach varied but was small compared to the scale of the disasters, according to federal data obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request.

Puerto Rico’s CCP, which was extended beyond two years to accommodate the high level of need, reached the most people. Of the island’s 3.2 million residents, 580,000 met with counselors for sessions lasting longer than 15 minutes. Yet even there, some areas appear underserved. In Ponce, 35 percent of residents applied for FEMA financial aid—one indication of how many people were affected—and only 7 percent received counseling sessions.

Texas has relied on the CCP for 35 disasters, some simultaneously—more than any other state or territory. “Responding to multiple disasters is nothing new for our program and for the state,” said Chance Freeman, director of Disaster Behavioral Health Services at the Texas Health and Human Services Commission.

In many ways—in part because of the repeated poundings—the state has one of the most advanced disaster mental health systems. Yet a review of its Harvey response in Houston shows that even there, relatively few survivors are reached by the federally funded counseling program.

Roughly 22,000 Houston residents received individual, family or group counseling within the 14 months the program was active, according to Public Integrity and CJI’s review. At the same time, about 341,000 people there applied for housing or property aid from FEMA.

Freeman says the state used that list of applicants to help identify the hardest-hit areas.

But in the nine Houston ZIP codes with the highest per-capita share of FEMA applicants—all lower-income, majority Black and Hispanic areas—1 percent of the population received counseling. That’s about the same level of help provided in some higher-income, majority-white ZIP codes, even though a smaller percentage of residents there applied for aid.

In Herndon’s ZIP code, which ranked second on that FEMA-application list, some 4,700 people asked for aid. Just 105 met with counselors.

Dr. Annelle Primm, chair of the All Healers Mental Health Alliance, a group that taps volunteers to fill gaps in the government response to disaster-struck communities of color, is not surprised by the data. The unequal distribution of assistance she sees in Black neighborhoods in particular, from food to disaster loans, adds to the emotional toll for residents.

“In this country, the response seems to assume that the people who are affected are middle-class white folks,” Primm said. “They really aren’t thinking about, well, what if the community that is affected was already behind the eight ball, or had preexisting challenges, which the disaster just made … that much worse?”

Presented with Public Integrity and CJI’s findings, a FEMA spokesperson said the program supplements local mental-health services, so “there is no universal ideal or adequate level of counseling post-disaster—it varies not only by locality but also by disaster.” The agency added that crisis counseling is available to all U.S. residents through the federal Disaster Distress Helpline.

The Harris Center for Mental Health and IDD, which ran the CCP in Houston after Harvey, said that the findings don’t include other forms of support beyond counseling. The agency led educational sessions with thousands of residents that, it said, could inform and motivate survivors to seek help from other mental-health organizations, religious groups, family and friends.

Freeman, of the Texas health department, said the program serves all survivors equally. Among the 16,000 who received individual counseling in Houston, 38 percent were Black, 30 percent were Hispanic and 18 percent were white, according to the counselors’ observations.

“More time would be great and more resources would be great,” he said, but “we’re not there to create a need that doesn’t exist. Communities are resilient.”

Stigma around mental-health care and people’s desire to be self-reliant both make it difficult to know when a community no longer needs aid, experts caution. After Katrina, teams dispatched to hard-hit communities found that no one stopped to talk if they set up a table with a “free crisis counseling” sign. “But when we began posting ‘tell us your hurricane story,’ people stopped,” said Danita LeBlanc, manager of Louisiana Spirit, that state’s crisis counseling program.

When Texas reached the end of its Harvey counseling program, 40 percent of the grant was unspent. Positions were never filled and some staff, including counselors, left before their contract was up. “This is not uncommon given the temporary nature of the program,” a state health department spokesperson said in an email.

The agency didn’t directly address a question about whether thousands more people could have been counseled with the unused funds. It said it exceeded its goals and got a commendation from the federal government. The money, $5.6 million, went back to FEMA.

The long, uneven road to recovery

How well or quickly someone recovers emotionally from a disaster can depend on how well and quickly they recover in other, more tangible ways.

“It’s not just initial exposure” to a flood or wildfire, said Sarah Lowe, a psychologist and professor at Yale School of Public Health. “It’s more than that: dealing with bureaucracies, finding someplace else to live, financial impacts.”

One example of those traumatic ripple effects: Major disasters worsen homelessness.

In the 2017-2018 school year—marked by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria—the number of homeless students jumped 57 percent in districts where a hurricane, flood, coastal storm or wildfire damaged property, according to a Public Integrity/CJI analysis of federal data.

In unscathed school districts that year, student homelessness was virtually unchanged.

The Houston Independent School District counted a little less than 7,000 students whose families had no home of their own before Harvey hit, including those doubling up in other people’s houses and living in motels. Afterward, their ranks swelled to nearly 30,000, more than in any other district nationwide.

Houston’s school district has spent the past three years helping families get back on their feet. But Lisa Jackson, senior manager of the district’s Department of Student Assistance Services, said the families of some students made homeless by the hurricane have yet to find housing.

The longer the recovery takes, the worse that mental-health outcomes can get. This was clear, experts said, from Louisiana after Katrina, where many lived in damaged homes for years and felt forgotten.

Recovery efforts after Harvey were widely applauded by both government officials and emergency management experts. But even in Houston, thousands of low-income homeowners are still seeking aid to repair hurricane damage to their homes, according to the city. Recent analyses show that part of the reason may be the unequal way the federal government distributes aid.

In one study, researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis found that bankruptcy rates in Houston after Harvey rose nearly 30 percent for flooded low-income households while remaining flat—or even declining—for flooded higher-income households. Emily Gallagher, a finance professor who co-authored the study, attributed that to the fact that those same low-income areas — as well as majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods — were also less likely to secure federal disaster aid.

In majority-white Houston neighborhoods like Greater Heights, for instance, the rate of approval for FEMA housing aid was 20 percent. In the Fifth Ward, a majority-Black neighborhood, the rate of approval dropped to 15.5 percent. This pattern was consistent throughout the city.

“It isn’t because there was less damage in minority areas,” said Gallagher, whose study controlled for that. Her conclusion wasn’t that FEMA is actively discriminating, but that the agency may not be accounting for the way that race in America, after decades of systemic discrimination, is linked “with factors that make it harder to get a grant.”

FEMA’s case workers do their best to help all people struck by disaster, regardless of their background, an agency spokesperson said: “To imply that FEMA does not or would not grant assistance to any survivor in need is grossly inaccurate, misleading and disturbing.”

Nationally, other studies have shown differences in aid. Nearly 60 percent of requests for federal disaster loans were denied from 2001 to 2018, and tens of thousands of other applicants were kicked out of the process before a decision was made, according to a Public Integrity investigation. Ninety percent of denials were due to “lack of repayment ability” or “unsatisfactory credit history,” one way that lower-income disaster survivors get shut out of recovery help.

Herndon applied for FEMA housing assistance just days after the storm. She was rejected weeks later: Her house was “Safe to Occupy,” FEMA wrote.

“I was sitting in my bedroom, and I could look all through my house,” said Herndon, who had torn out her walls because black mold had overtaken them. “That was the most disheartening thing.”

For months, Herndon met with countless nonprofits to no avail. She said she appealed FEMA’s denial three times. Finally, in early 2018, Herndon got two bits of good news. FEMA reversed its decision and awarded her $9,800. Then a nonprofit called Team Rubicon agreed to rebuild her house free of charge.

Sandra Edwards, who lives in the Fifth Ward not far from Herndon, was less fortunate.

Edwards’ $47,000 home—like Herndon’s, located outside the 100-year floodplain—was all but destroyed by the flooding. FEMA awarded her $11,000, money she used to rip out her walls and pay for a few months of temporary housing. For over a year, Edwards, 54, lived without walls, gas or hot water. Parts of her floors and ceilings were missing. One side of her house had sunk several inches into the ground. She wrote frenzied, handwritten appeals for more aid—“I am Homeless!!!” she declared in one—but was denied.

In the fall of 2019, she found West Street Recovery, a local nonprofit. The organization had enough money to repair part of her home, though about a third remains unfinished. Edwards moved back this March. A city application to finish her home is on hold.

The experience took an enormous toll on her mental health, she said. She’d be sitting in a neighborhood meeting, for instance, and break down in tears.

“If you sit back and think about all the stuff you going through,” said Edwards, “it just makes you don’t want to be here anymore.”

‘Such a betrayal’

Few Americans are protected from disaster-related stress this year. As COVID-19 exacts collective trauma, more than 40 states and territories so far have launched federally funded crisis counseling programs in response.

But the need to stay physically distanced upends the way disaster counseling usually operates. States scrambled to organize video calls and are relying more on hotlines. Unable to send people door to door, they’re hoping that online announcements, posters in stores or pamphlets with food aid will get the word out that help is available. In the midst of all this, some officials are also trying to support the mental health of people who survived extreme weather before the pandemic hit—and they’re bracing for more climate disasters.

“Just being able to reach out … has been a challenge,” said Garcia Bodley, director of the Louisiana Department of Health’s crisis counseling program. “We’re missing that connectivity we’ve had in the past.”

For the survivors of recent hurricanes, floods and wildfires, the coronavirus represents yet another weight. About three-quarters of those who took the Public Integrity/CJI survey said the pandemic is compounding their previous disaster experience, from piling on more stress to further eroding their finances.

Both Herndon and Edwards—older Black women with chronic lung problems—fall into high-risk categories for the virus. They’re afraid of getting sick. Herndon says she’s spending more time at home alone, worries intensifying.

Many of the survey respondents are profoundly anxious about the future. Nearly all were concerned that their community will be hit by more disasters; two-thirds were very concerned. A few had already moved at least in part for that reason.

And they’re deeply frustrated about the government’s preparedness for and response to disaster. Two-thirds rated it “poor.” Only 12 percent said it was “good” or “great.”

The problems they identified ranged from scant rebuilding help to local development decisions that worsen flooding, a problem so common that the flood-survivor organization Higher Ground now has more than 50 chapters in the U.S. And then there’s the halting, often nonexistent response to the warming climate supercharging storms and fires.

“After a disaster, if the government does not declare a climate emergency and start acting like it, it’s just such a betrayal,” said Margaret Klein Salamon, a psychologist who started the advocacy group The Climate Mobilization after living through Superstorm Sandy. Providing mental-health support to survivors even as elected officials fail to rein in global warming “is like a Band-Aid. How can we trust a government that does so little to protect us?”

Even when it’s working well, crisis counseling may be only the start of what survivors need. Counselors try to connect people with longer-lasting services when required—that’s the logic for why the program ends after a year. But America’s fragmented system of mental-health care is strapped at the best of times.

Almost a quarter of all U.S. adults with a mental illness reported that they were unable to get the treatment they needed, according to the advocacy group Mental Health America. Some of the most common reasons: lack of insurance, lack of providers, an inability to cover copays.

Asked how the country should change its response to psychological damage in an era of worsening disasters, FEMA said: “There is a need for investment in mental health services at every level, but especially at the local, state, tribal, and territorial levels. Survivors will always receive the best, most appropriate services from those who live in their own community.”

Using data from FEMA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Integrity and CJI identified 178 U.S. counties or municipalities predisposed to disaster-driven mental illness. All have vulnerable populations that were hit by multiple, property-damaging hurricanes, floods or wildfires in the last 10 years. At least a quarter of those places have poor access to psychological care, according to County Health Rankings.

In Harris County, Texas, which includes Houston, 29 percent of Black and 33 percent of Hispanic residents were unable to afford medical care in 2017, according to state data. That’s compared with 10 percent of whites. Mental-health providers in Houston are concentrated on the southern and western sides of the city, away from Herndon and Edwards’ neighborhoods.

Herndon tried to find a therapist several times after Harvey. But when she began calling the dozen or so people she’d been given by her insurance provider, many were no longer taking her insurance. The others never called back, she said. “I stopped actively looking for help,” she added. “It was making me more depressed.”

Edwards, for her part, said she looked into therapy but could not afford the copays.

Access to care can make a huge difference. Between 2015 and 2017, Sherri Blatt, 54, was flooded three times in her neighborhood of Robindell in southwest Houston. Blatt, a recovering alcoholic, relapsed and was overwhelmed with stress each time.

After the last flood—Harvey—she went into therapy and was diagnosed with PTSD. Like Herndon, she continues to be frightened by the sound of rain. But she’s in a much better place—and almost two years sober. Today, she works for a rehabilitation center helping others.

“If I flooded today … it would look different for me,” she said. “I have a different support system that can carry me through.”

Herndon has accepted that she may never get professional help, but she learned a few breathing techniques that help her cope. She also joined a neighborhood group, the Harvey Forgotten Survivors Caucus, where she advocates for more mental-health resources. During the pandemic, they’ve been meeting by phone weekly.

Still, she worries about what future storms may bring. In the years since her husband died, the warming climate has amped up the risks in her now flood-prone neighborhood. She thinks often about her promise to stay.

“And, look, I’ve been keeping it,” she said. “I’m still here.”

Kio Herrera and Chris Zubak-Skees contributed to this article. Dean Russell is a reporting fellow for Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School. Funding for CJI comes from the school’s Investigative Reporting Resource and the Energy Foundation. Jamie Smith Hopkins is a senior reporter with the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative newsroom in Washington, D.C.