<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/stevendepolo/4498875608/sizes/m/in/photostream/">stevendepolo</a>/Flickr

I’ve always recoiled from highly processed and packaged fake meat: you know, turkeyesque tofu logs for the holiday table, or pink, spongy “not-dogs” for the summer grill. But in last Sunday’s New York Times, Mark Bittman raised a provocative question:

Isn’t it preferable, at least some of the time, to eat plant products mixed with water that have been put through a thingamajiggy that spews out meatlike stuff, instead of eating those same plant products put into a chicken that does its biomechanical thing for the six weeks of its miserable existence, only to have its throat cut in the service of yielding barely distinguishable meat? Why, in other words, use the poor chicken as a machine to produce meat when you can use a machine to produce “meat” that seems like chicken?

Bittman’s point is spot-on. You can’t directly eat the kind of corn and soy that dominates US farmland—it isn’t readily digestible. Modern livestock farms are really factories for turning those crops into animal flesh that can be transformed into steaks, chops, wings, nuggets, and whatnot. And in doing so, Bittman points out, factory farms rack up enormous collateral damage: horrific suffering for sentient creatures, huge stores of manure that can’t be safely recycled into soil, over-reliance on antibiotics, routine abuse of labor in factory-scale slaughterhouses, and more.

It’s especially tragic, then, the meat produced in these factories is pretty flavorless, especially if you’ve tasted a truly free-range chicken against a factory one, or a grass-fed burger alongside its feedlot analogue. So why, Bittman asks, not leave the birds, hogs, and cows out of it and just directly consume the feed crops after they’ve been processed to taste something like meat? By doing do, you sacrifice little or no flavor, while sidelining a whole raft of destructive practices.

Bittman points to a company called Savage River Farms that has produced a soy-based product that mimics chicken, down to the way it shreds. Bittman says he couldn’t tell it from real chicken when he was served a burrito made with it.

Here is where Bittman lost me. The ingredients of Savage River Farms chicken strips that Bittman tasted run as follows: water, soy protein isolate, pea protein, amaranth, chicken flavor, carrot fiber, canola oil, titanium dioxide (food coloring), and white vinegar.

Ugh. How depressing. The product reinforces the industrial food model: You isolate components of whole foodstuffs—the the protein in soybeans and peas, the fiber in carrots—and combine them into some composite that derives its flavor from the laboratory (“chicken flavor”), not the farm field. In his book In Defense of Food, Michael Pollan labeled such mix-and-match food engineering “nutritionism,” and argued persuasively that what you end up with is less than the sum of the parts. You’re almost certainly better off eating carrots and edamame—young soybeans that actually can be eaten by people—than you are ingesting mashed-up isolated components of them. And that’s to speak nothing of the chemical processing required to create those isolates in the first place. As my colleague Kiera Butler reported back in 2010, to create soy protein isolate, manufacturers often subject soybeans to the chemical hexane, a neurotoxin.

However, there do exist meat substitutes that are made of whole foods—and actually taste better than factory-farmed chicken. Why not turn to them?

Consider the falafel: crisp little orbs of deliciousness, consisting of ground chickpeas (or, sometimes, fava beans) that have been spiced up, fried, and deposited into pita bread along with veggies and condiments. Falafel is an an iconic street-food snack throughout the Middle East. It’s also pretty big in New York City, where it kept me alive during a low-paid internship back in the late 1980s.

Unlike Savage Farms’ “chicken” strips, which are freshly hatched from some guy’s laboratory, falafel has been around a while. “Their origin cannot be traced and is probably extremely ancient,” declares the authoritative Oxford Companion to Food. And rather than being tarted up to taste like something that’s dreadfully mediocre—factory-farmed chicken—falafel tastes of something wonderful: itself.

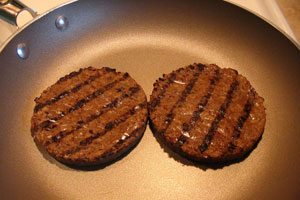

Then there’s tempeh, which the Companion calls “the Indonesian solution to making this indigestible vegetable [the soybean] into a nutritious food.” Tempeh is made simply by fermenting whole dry soybeans, and has become “vital to the nutrition of many Javanese, whose diet is rice-based and contains little animal food.” I should add that, like so many fermented things, it’s also really good. And unlike falafel, you can buy it pre-packaged and cook it at home easily.

Then there’s the most famous traditional meat substitute of all, tofu—which, reports The Oxford Companion, has existed in China for at least 1,000 years. Tofu is essentially curdled soy milk—the curdling process makes the protein in soy more available to human digestion and in particular frees up the key amino acid lysine. I have had spectacular tofu in traditional Chinese restaurants in New York, but I confess I’ve never mastered the craft of cooking it at home.

All of that said, Bittman is right that it’s time to wean ourselves from eating so much factory-farmed meat. The practice not only perpetuates all of the abuses Bittman spells out, but it’s also likely damaging eaters’ health, new research suggests. Bittman cites hopeful statistics showing that more and more Americans are ready to cut back on meat. And if it takes weird strips formed from isolated soy protein and the like to push on the transition, then so be it, I suppose. But to really push us beyond the industrial-food model and its various insults, we’ll need to embrace whole-food meat alternatives.

What the country needs now is more corner falafel joints, like the kind you can still find in certain regions of lower Manhattan and other places where Middle Eastern immigrant communities exist, like suburban Detroit. I’m confident that if more people were exposed to it, falafel could become wildly popular in the United States. And it may well be possible to make falafel at home without too much fuss. I’m going to try it this week, using a recipe from one of our greatest cookbook writers: Mark Bittman.