Shutterstock/Tomasz Darul

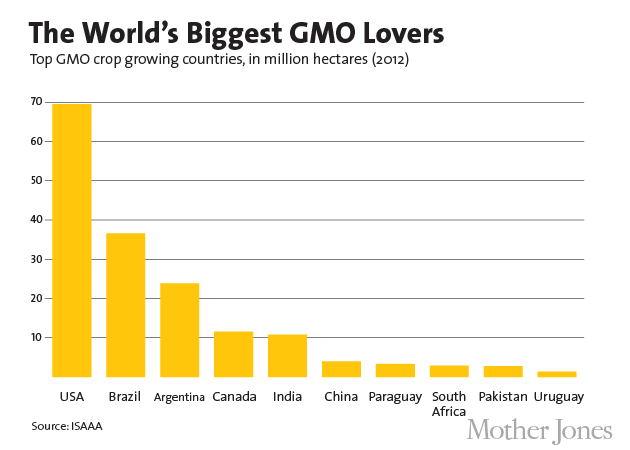

Despite persisting concerns over genetically modified crops, a new industry report (PDF) shows that GMO farming is taking off around the world. In 2012, GMO crops grew on about 420 million acres of land in 28 countries worldwide, a record high according to the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications, an industry trade group.

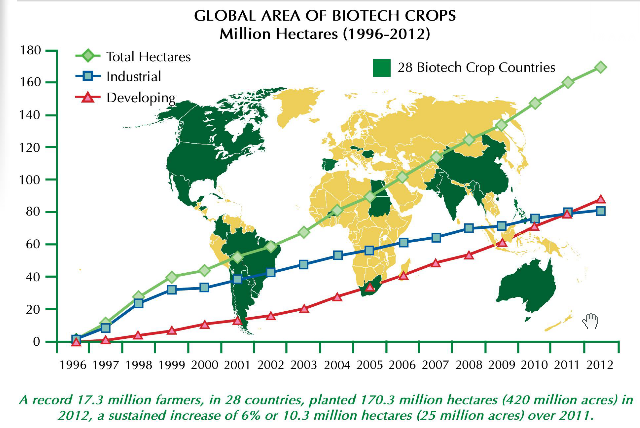

If all the world’s GMO crop fields in 2012 were sown together, it would blanket almost all of Alaska. As the chart from the report shows, globally GMO farming has been on an uninterrupted upward trend. What’s especially noteworthy is the growth of GMO farming area in developing nations (see red line), which surpassed that in industrial nations for the first time in 2012. The ISAAA’s report doesn’t project into the future, but we may see this upward trend continue as “a considerable quantity and variety” of GMO products may be commercialized in developing countries within the next five years, according to a recent UN Food and Agriculture Organisation forum (PDF).

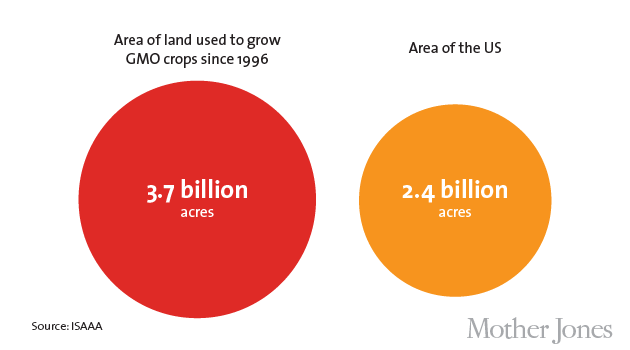

The ISAAA says the area of land devoted to genetically modified crops has ballooned by 100 times since farmers first started growing the crop commercially in 1996. Over the past 17 years, millions of farmers in 28 countries have planted and replanted GMO crop seeds on a cumulative 3.7 billion acres of land—an area 50 percent larger than the total land mass of the United States, the group adds.

“This makes biotech crops the fastest adopted crop technology in recent history,” ISAAA chair Clive James states in the report. “The reason—it delivers benefits.”

What kinds of benefits? According to the ISAAA, GMO farming has reduced use of pesticides, saved on fossil fuels, decreased carbon dioxide emissions, and “made a significant contribution to the income of < 15 million small resource-poor farmers” in developing countries. These small-scale farmers now make up over 90 percent of all farmers growing GMO crops, the group states.

But just looking at the United States—consistently the biggest GMO crop producer in the world by a long shot—there is much reason to doubt on some of ISAAA’s claimed benefits. (More after the chart.)

As my colleague Tom Philpott reported earlier this month, nearly half of all US farms now have superweeds that can resist Monsanto’s herbicide Roundup, which is sprayed on crops engineered by Monsanto. A 2012 study by Washington State University showed that overall, GMOs lead to a net increase in pesticide inputs. And a Department of Agriculture-funded paper out this month found that genetically modified doesn’t necessarily mean higher crop yields (PDF), one of GMOs’ biggest selling points.

There’s been some doubt about the wisdom of GMOs in the rest of the world, too. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation has pointed out (PDF) some of the downsides of GMOs for small farmers and consumers, such as pest resistance, contamination of non-GMO crops, and potential toxicity of GM foods and products. According to the FAO, in 2011, 161 countries ratified the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, an international agreement designed to ensure the safe transfer and handling of GMO crops “that may have adverse effects on the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, taking also into account risks to human health, and specifically focusing on transboundary movements.”

Back in January, more than 60,000 Mexican small-scale farmers marched through Mexico City in protest against Monsanto, Latin American news site Voxxi reported. The company has been trying to obtain unrestricted permission to plant its genetically modified corn in the country. The farmers fear that widespread planting of the modified corn will contaminate native breeds. “For peasant farmers, GMOs represent looting and control,” Olegario Carrillo, president of the Mexican small farm organization UNORCA said at the protest.

As the FAO notes, in most cases these GM technologies are proprietary, developed by the private sector and released for commercial production through licensing agreements. Adoption of GM technologies has also spurred a range of social and ethical concerns about restricting access to genetic resources and new technologies, loss of traditions (such as saving seeds), private-sector monopoly, and loss of income of resource-poor farmers. There’s also reason to worry about legal battles. Last week the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a 2007 case Monsanto filed a against Vernon Hugh Bowman, a 75-year-old Indiana farmer. Bowman, Monsanto claims, violated the corporation’s patent rights by buying and planting second-generation Roundup Ready seeds, which Monsanto contractually forbids. (Mother Jones‘ Maggie Severns has more on this here.)

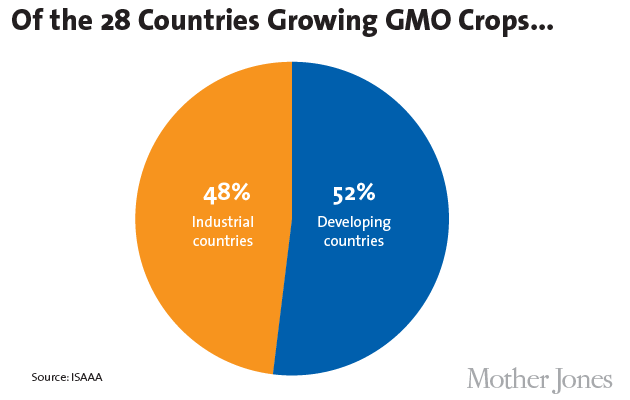

Nonetheless, by ISAAA’s count, developing countries show no signs of slowing their adoption GMO crop technologies. In 2012 they surpassed industrial countries in their share of the world’s GMO crops, the group reports.