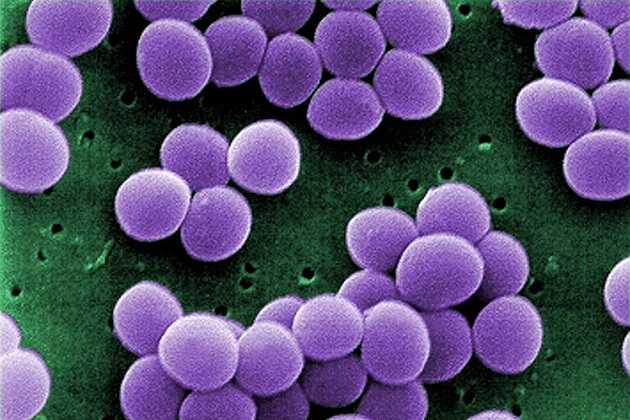

<a href="http://In 2009, for example, an analysis of FDA data by Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future found that US livestock farms burned through more than 10 million pounds of tetracycline—compared to total human consumption of all antibiotics of just 7.3 million pounds." target="_blank">branislavpudar</a>/Shutterstock

Almost 80 percent of antibiotics consumed in the United States go to livestock farms; antibiotic-resistant pathogens affecting people are on the rise; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has made the connection between those two developments. So what’s the Food and Drug Administration doing to curb overuse of these key drugs on animal farms?

On Wednesday, the FDA spelled it out by releasing recommendations (text [PDF]; press release) on how drugmakers should “voluntarily” modify the way they administer antibiotics to the meat industry. It also released a proposal that would require a veterinarian’s signoff for antibiotics that are commonly used in human medicine—which would represent a major departure from the antibiotics free-for-all that holds sway today.

Some of these “medically important” antibiotics are widely used on livestock farms. Take tetracycline, a drug used in human medicine to treat urinary-tract infections, acne, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and other maladies. In 2009, for example, an analysis of FDA data by Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future found that US livestock farms burned through more than 10 million pounds of tetracycline—compared to total human consumption of all antibiotics of just 7.3 million pounds.

The FDA will be taking comments on this proposal, known as the Veterinarian Feed Directive, for the next 90 days.

Meanwhile, the new recommendations—also released Wednesday—narrows the “prevention” loophole, which I pointed out when the FDA first floated the new system in April 2012. Currently, factory livestock farms use antibiotics in three ways. The first is what the FDA calls “production”: the livestock industry discovered in the 1950s that when animals get small daily antibiotic doses, they put on weight faster, and the practice has been embraced ever since. No. 2 is disease “prevention”: when you concentrate animals together, they’re prone to illness and pass diseases among themselves quickly. Daily antibiotic doses can boost their immune systems and keep them from coming down with bugs. The third use is disease treatment, the one we humans are familiar with: you come down with a bacterial bug and and treat it with antibiotics.

Of course, there’s little distinction between giving animals small daily doses of antibiotics to prevent disease and giving them small daily doses to make them put on weight. The industry can simply claim it’s using antibiotics “preventively,” continuing to reap the benefits of growth promotion and continuing to generate resistant bacteria. That’s the loophole.

But the document released Wednesday delivers five pretty specific guidelines on how “prevention” should be defined, including that antibiotics prescribed preventively should be “targeted to animals at risk of developing a specific disease,” i.e., not given willy-nilly to “prevent” the theoretical possibility of some hypothetical disease. It adds: “FDA would not consider the administration of a drug to apparently healthy animals in the absence of any information that such animals were at risk of a specific disease to be judicious.” That’s the strongest statement I’ve seen from the FDA on the prevention loophole.

Laura Rogers, who directs the Pew Charitable Trusts’ human health and industrial-farming campaign, calls that language “promising.” She adds: “This is the first official FDA policy on disease prevention, acknowledging that it is a problem.”

There does, of course, remain the whole “voluntary” problem, as Jean Halloran, director of food policy initiatives for Consumers Union, stressed. “We have urged that these changes be mandatory, given how urgent the problem of antibiotic resistance is,” Halloran said in a statement.

And US Rep. Louise Slaughter (D-N.Y.), who since 2007 has been heroically pushing legislation that would definitively crack down on antibiotic use on farms, issued the following lament:

The FDA’s voluntary guidance is an inadequate response to the overuse of antibiotics on the farm with no mechanism for enforcement and no metric for success. Sadly, this guidance is the biggest step the FDA has taken in a generation to combat the overuse of antibiotics in corporate agriculture, and it falls woefully short of what is needed to address a public health crisis.

The fate of Slaughter’s antibiotic crackdown proposal, called the “Preservation of Antibiotics for Medical Treatment Act,” illustrates the industry’s power in shaping policy. Check out the roster of groups that lined up to lobby on the 2011 version of Slaughter’s bill, courtesy of OpenSecrets—it reads like a meat/pharma industry trade convention floor show. The groups have lavished millions on the effort to defeat Slaughter’s bill, which has thus far never come close to passing.

With congressional action looking impossible, the FDA’s weak tea is all we have. But it could be weaker—at least the FDA gummed up that loophole with a few potentially substantial obstacles to agribusiness as usual.