Wavebreakmedia/iStock/Getty

On Tuesday, the Food and Drug Administration announced it would delay indefinitely the launch of the redesigned nutrition facts labels that large food companies were supposed to comply with by July 26 of next year. The FDA says the extension is meant to give companies more time to figure out how to get the new labels onto their products, but those who have already hustled or spent extra money to comply with the deadline aren’t too happy about the shift in plans.

The delay is one in a series of changes to Obama-era reforms that has sent the food world reeling in the last couple of months. After a May decision to put off requirements to list calorie counts on menus, the Center for Science in the Public Interest’s Director of Nutrition Policy Margo G. Wootan remarked that “the Trump administration is randomly sowing chaos.”

Here’s the lowdown on some of these recent food policy delays:

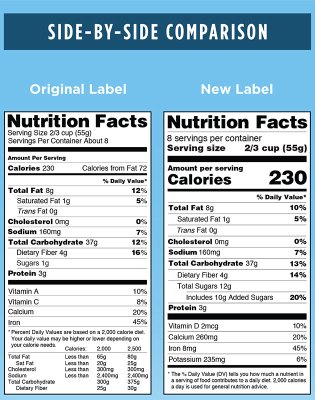

Nutrition labels: Any packaged food you buy has a label with its nutritional information. After years of complaints about the format and content of this standardized label, in May 2016 the FDA finalized a new label that would “make it easier for consumers to make better informed food choices.” The font is bigger, for one thing. And perhaps even more importantly, now added sugars (sweeteners added to a product during the processing) will have to be displayed—along with a percent of the recommended daily amount those sugars constitute.

Three quarters of packaged foods contain added sugars, and Americans consume, on average, several times the amount of sugar deemed healthy every day. “Besides helping consumers make more informed choices, the new labels should also spur food manufacturers to add less sugar to their products,” stated CSPI President Michael F. Jacobson. Here’s a side-by-side comparison of the old and new Nutrition Facts Label:

But with the delay of the compliance deadline, now only some foods you buy will show these new labels, at least for now. The delay came about as a result of heavy lobbying by some food groups, who see the new labels as an onerous change. But that leaves the companies that have already complied on certain products—like Nabisco’s Wheat Thins and PepsiCo’s Lay’s potato chips—with a potential disadvantage. “We’ll have the added sugar declaration and the percent daily value, but our competitors won’t?” Mars executive Brad Figel told the Washington Post. “That just ends up confusing customers.”

Calorie counts: Former President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, included a provision that required chain restaurants, grocery stores, and other food establishments to disclose on signs and menus the number of calories a customer might find in any prepared foods and beverages. Americans tend to underestimate the number of calories in dishes, especially when they are out to eat—and we consume one third of all calories outside the home. The calorie count rule was an effort to curb obesity and encourage restaurants to offer healthier choices and smaller portions. It garnered widespread support from industry groups–and consumers, 80 percent of whom supported labeling in chain restaurants in one survey.

On May 4, a day before restaurants were supposed to begin displaying this information, the FDA delayed the requirement for another year. Some industry groups had lobbied the agency to drag its feet on the rule’s implementation; for instance, the National Association of Convenience Stores and the National Grocers Association had complained in an April letter that the rule was unclear and costly. But Earthjustice lawyer Peter Lehner, who is representing the Center for Science in the Public Interest and the National Consumers League in a lawsuit against the US Department of Agriculture, sees the delay as “another example of the Trump Administration’s willingness to accommodate even unfounded and partial industry opposition to the detriment of the health and welfare of people and families across the country.”

School lunch: On May 1, the USDA put out a press release entitled “Ag Secretary Perdue Moves to Make School Meals Great Again.” The very Trumpian decree, which promised to “provide greater flexibility in nutrition requirements for school meal programs,” does so by loosening stipulations that schools must provide whole-grain-rich breads and pastas; rolling back targets for reducing sodium intake in school lunches; and easing the requirements on the allowable fat content of chocolate milk. Schools were going to have to decrease the amount of salt in meals from 1,230 milligrams to 935 milligrams by 2020*; now, they won’t need to change the amount of sodium until after 2020.

The American Heart Association was miffed at Perdue’s announcement, warning that “children who eat high levels of sodium are about 35 percent more likely to have elevated blood pressure, which can ultimately lead to heart disease or stroke.”

Salt: The Obama administration released voluntary sodium reduction guidelines in June 2016 to try to encourage Americans to reduce their sodium intake from 3,400 milligrams a day to under the recommended 2,300 mg.

Fast forward a year, and Politico reports that the new 2017 appropriations bill now prohibits the FDA from using any funding to “develop, issue, promote, or advance any regulations applicable to food manufacturers for population-wide sodium reduction actions or to develop, issue, promote, or advance final guidance applicable to food manufacturers for long term population-wide sodium reduction actions until the date on which a dietary reference intake report with respect to sodium is completed.” As Food Politics blogger Marion Nestle writes, this dietary reference intake report “by the way, will take years.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the timeline of the original sodium reduction targets for school lunches. The target for 2020 was under 935 mg of sodium with the goal of reducing intake to under 650 mg by 2022.

This article has been revised.