Jan Woitas/ZUMA

Chicken is America’s favorite meat. Producing it is a $30 billion business, dominated by a few large players. So why should the US Small Business Administration be facilitating taxpayer-backed loans to these companies’ de facto subsidiaries?

That’s the question posed by a blunt new audit by the Small Business Administration’s Office of the Inspector General. The SBA was founded as a federal agency in 1953 to “aid, counsel, assist, and protect the interests of small business concerns” while its OIG exists to “provide independent, objective oversight” of the office.

Between 2012 and 2016, the OIG report states, the SBA backed 1,535 loans, worth a total of $1.8 billion, to contract chicken farmers. (Another federal entity, the US Department of Agriculture’s Farm Service Agency, offers similar loan support to poultry growers.) On the surface, contract chicken farmers might seem like genuine independent businesses. They provide full-grown birds to the large companies that slaughter, cut up, and package them into the drumsticks, breasts, and thighs we buy at the supermarket.

But here’s the thing, according to the OIG: In reality, those farmers don’t operate independently at all. They are essentially the production arm of the companies, operating at their whim. The farmers are offered a contract, typically covering a single flock, to grow birds from the chick phase to slaughter weight. The company provides farmers with the chicks and the feed. The farmers, in turn, are paid a fee to raise the birds (which they never own), in facilities whose size and design is dictated by the companies.

The farmers are financially responsible for building and maintaining those facilities—typically, 40 foot by 500 foot ventilated barns—and they’re quite expensive. According to Sally Lee, associate director of Rural Advancement Foundation International-USA, a farmers’ rights group, an “average new chicken house costs $300,000 to build, and the average chicken farm today has at least 4 houses, though the current trend is to build new farms with many more.”

That’s where the SBA comes in. The agency has been helping farmers secure bank financing to build chicken houses by ensuring the loans will be paid back even if the borrower defaults, the OIG audit states. But under the agency’s mandates, it should only be providing that service for small independent businesses—and contract chicken growers shouldn’t qualify, the OIG argues. The big poultry companies exercise “such comprehensive control over the growers” that the farms should be considered company affiliates, not independent operations.

The control enjoyed by the chicken companies over their contract farmers is impressive: They dictate “how to inspect flocks and broiler houses, prescribing where and how to walk through the houses, the frequency and timing of inspections, and how to record the results.” Other factors controlled by the companies include “broiler house lighting, heating, ventilation, and cooling, flock feeding, watering, and the culling of birds.” Then there’s those pricey barns: The companies give “detailed construction specifications for the grower’s broiler houses,” including grading, equipment, signage, and construction oversight.

The companies also routinely demand “significant capital upgrades” to existing barns and equipment. These mandatory expenditures lock farmers in a debt cycle, often forcing them to “seek additional funding” from the SBA loan program, the OIG report states.

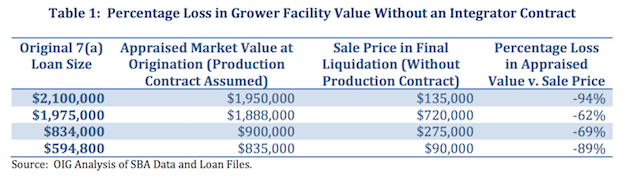

The big processors can also simply decide not to renew farmers’ contracts—and that can mean the collapse of the farm. Because without a contract, those $300,000 chicken houses are essentially worthless. To drive its point home, the report details the fate of several poultry farms that had received SBA loans and then lost their production contract:

In essence, the report lays out two scandals. One is that the Small Business Administration is helping meat-packing firms with billions of dollars in annual revenues get taxpayer-backed small-business loans to build out their chicken production capacity. The second is that these farmer-contractors endure kind of debt-driven serfdom. As a 2014 USDA study showed, contract poultry farmers on average “are likely to earn about $11.50 an hour,” after accounting for operating and interest expenses.

In a recent statement, Mike Weaver, president of the Organization for Competitive Markets, an advocacy group that defends the interests of independent farmers in corporate-dominated agriculture markets, called the OIG’s analysis of the chicken market “no surprise.” He called for federal antitrust action to “ensure poultry growers can operate as small businesses” and to “stop subsidizing increased production for these multinational corporations by American taxpayers.”

Instead, Weaver noted, the Trump administration is moving in the opposite direction. Last October, the USDA rolled back rules, finalized late in the Obama administration and known as GIPSA, that would have boosted farmers’ ability to push back in court against the chicken companies’ unfair practices.

As for the Small Business Administration and its habit of backing loans to poultry farmers, the agency has until August 31 to address the OIG’s concern that such entities aren’t independent small business and thus shouldn’t be eligible for related loans. Sen. Cory Booker, (D-NJ), added to the pressure by attaching an amendment to a Senate bill demanding that the SBA report to Congress on how officials have addressed the OIG report’s findings. In its mission statement, the SBA says it aims to “preserve free competitive enterprise.” Its de facto support of Big Poultry would appear to contradict that goal.